Fall of the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera

[7] Small and medium-sized enterprises also protested against the interventionist policy which they considered to be aimed at favoring the large and monopolistic companies and also harmed the consumer because "free competition is an indispensable condition for a better quality and cheaper production", as the Superior Council of Chambers of Commerce, Industry and Navigation stated at the end of 1925, and reiterated at the beginning of 1929: "The government has long since abandoned its harmonizing function.

[13][14] "When the social order was no longer immediately threatened, the Moroccan problem had been solved and the king began to show unequivocal signs of disliking the dictatorship, a growing alienation of the armed forces from Primo de Rivera became evident", affirmed Shlomo Ben-Ami.

[16] An opinion shared by José Luis Gómez Navarro: "From September 1925 onwards, all the military policy of the dictatorship, from the development of the war in Morocco with the landing of Al Hoceima to the changes in the promotion systems, meant the triumph of the spirit and the model of the Africanist army over this of the junteros, reopening and aggravating this confrontation".

[19] Alejandro Quiroga makes a similar assessment: "The appointment of Francisco Franco as director of the General Military Academy of Zaragoza only confirmed the Africanist bias of the dictator in the eyes of many peninsular chiefs and officers close to the Juntas".

The king intervened, which had its effects, since the dictator was forced to agree on a verbal pact with the artillerymen, also to prevent them from joining the coup d'état that General Aguilera was plotting, and which would be known as the Sanjuanada: promotions for war merits would only be granted exceptionally and would be subject to appeal before the Third Chamber of the Supreme Court.

The conspiracy involved the liberal generals Valeriano Weyler and Francisco Aguilera, and prominent members of the "old politics" such as Melquiades Álvarez, who drafted the manifesto A la Nación y al Ejército de Mar y Tierra (To the Nation and the Army of Land and Sea).

The most serious incident was led by the students of the School of Agricultural Engineers, headed by Antonio María Sbert, who did not attend a ceremony presided over by the king in protest because Primo de Rivera rejected the petition they wanted to present to him for not being made "through the regulatory process".

[66] Nor did the propaganda deployed by the official media, such as the newspaper La Nación, accusing the students of being manipulated by the "bad Spaniards" and by the "enemies of the Regime" and the mobilization of the Patriotic Union and the celebration of numerous acts in homage to the dictator, in which Primo de Rivera himself participated on many occasions, to "highlight before foreigners the true national opinion",[67] put an end to the revolt.

[72] The first conflict of the Dictatorship with the intellectuals took place a few weeks after the coup and had as its epicenter the Ateneo de Madrid when, in mid-November 1923, the Board chaired by Angel Ossorio resigned and suspended the planned activities in protest that a government delegate was present at each of the events to be held, to avoid criticizing the Directory as had already happened in the conference delivered on November 7, by the former deputy Rodrigo Soriano entitled "Yesterday, today and tomorrow".

Months later Unamuno did not avail himself of the amnesty decreed on July 4, 1924, by the Directory and went into self-exile in France —when leaving Fuerteventura he said: "I will return, not with my freedom, which matters nothing, but with yours"—,[77] becoming, as Eduardo González Calleja has pointed out, "the most enduring myth of the movement of intellectual opposition to the regime".

The latter was answered with a scornful "official note" from Primo de Rivera, which "was the first sign of the violent anti-intellectualism that from 1926 onwards would grip the dictator and irreversibly erode his relations with the Spanish intelligence elite", states González Calleja.

A few days later the students protested against the filling of the chair that Unamuno had left vacant at the University of Salamanca, with whom the professor Luis Jiménez de Asúa expressed his solidarity, for which he was deported to the Chafarinas Islands on April 30, from where he was able to return on May 18, thanks to the amnesty dictated on the occasion of the King's fortieth birthday.

[84] In April 1929, Federico García Lorca and Pedro Salinas, two outstanding poets of the so-called Generation of '27 whose members had not interfered in political issues (they would do so during the Second Republic, mostly in favor of it), published an open letter to intellectuals in which they expressed their opposition to "apoliticism" and appealed to men with a liberal sensibility.

[115][116] In the manifesto made public by Sánchez Guerra, in which he included the letter he had sent to the king a year earlier, he proposed the calling of a Parliament through which "the sovereign nation would freely dispose of its destiny and establish the rules within which the future rulers would have to move and develop their action".

These parties also attracted the professional classes, especially in the provinces, where teachers, doctors, engineers and lawyers found it increasingly difficult to earn a decent living, due to the constant rise in prices and, from 1929 onwards, the scarcity of new job opportunities.

[138] After the failure of the Sanjuanada coup d'état of June 1926, Macià set in motion the planned invasion of Catalonia by a small army composed of escamots that after crossing the border through Prats de Molló, would take Olot and then fall on Barcelona, where simultaneously the general strike would be declared, and with the collaboration of a part of the garrison the Catalan Republic would be proclaimed.

In the first discussion that took place in the National Congress held clandestinely in Barcelona in April 1925, the former won when the proposal of collaboration "with as many forces tending to the destruction of the current regime by violent means" was approved, although with the proviso that "these pacts do not imply that commitments of any kind are contracted to limit the scope and development of the revolution which, at all times, we must promote to its radical and positive extremes".

[162] The new Penal Code approved in September 1928, and which would be repealed by the Second Spanish Republic, included in the crime of rebellion strikes and work stoppages, as well as considered as an attack on authority the aggression against members of the Somatén, even if they were not exercising the functions of their office.

The Tribunal would be presided over by a military judge and would investigate cases affecting the security of the State, and could open rapid indictments for crimes of conspiracy, rebellion, etc., which meant in practice that the government could, for example, suspend from employment and salary those civil servants who were hostile to the regime.

[166] In April 1929, a draft Law of Public Order was discussed, which expanded the discretionary powers of the government to suppress constitutional guarantees, to proceed with arrests and searches without a warrant, as well as the expulsion of dangerous foreigners, and to declare a state of war.

[175][176] A new clash occurred at the beginning of February 1929, when the king, advised by his mother María Cristina de Habsburgo,[177] resisted signing the decree granting extraordinary powers to the Government, the somatén and the single party Unión Patriótica for the repression of "subversive" activities after the failed coup d'état of the previous month led by Sánchez Guerra.

[180][181][182] Javier Tusell and Genoveva García Queipo de Llano have pointed out, on the other hand, that the failed coup d'état gave Alfonso XIII "the definitive sensation that the weakness of the regime was patent and that important questions about the future were opening up.

"It would be weakness and desertion improper of men who accepted to govern under very difficult conditions... to allow themselves to be impressed and depressed by clandestine small talk emanating from discontented sectors, stubborn in rebellion, which neither in quantity nor in quality represent a hundredth part of the Spanish people", he added.

[202] His final transition plan was discussed at a government working dinner, also attended by the president of the National Consultative Assembly José Yanguas Messía, held at the Lhardy restaurant on December 3, in commemoration of the fourth anniversary of the constitution of the Civil Directory.

[207] On December 31, 1929, the Council of Ministers presided by the king debated the "Lhardy plan", but "Alfonso XIII asked for a few days to reflect..., which meant a tacit withdrawal of the royal confidence and the official opening of the last crisis of the regime", says González Calleja.

That day he announced by means of an "unofficial note" that he was going to consult the ten general captains (and the chiefs of the three maritime departments and of the Moroccan forces and the directors of the Civil Guard, Carabinieri and Invalides), so that they could evaluate the work of the Dictatorship and so that with their authority they could settle the "high and low intrigues" that were taking place at that time.

[224] On January 27, Primo de Rivera received the ambiguous answers of the general captains[229] which were due, according to Shlomo Ben-Ami, to his desire to distance the Army from the Dictatorship, "a sinking ship" and to the fact that most of them were friends of the king or very loyal to him as sovereign.

At the exit Primo de Rivera announced that he had resigned "for personal and health reasons" and that Alfonso XIII had entrusted "to form a Government to General Dámaso Berenguer, a discreet and reserved man in his judgments, of serene character and very well liked in the country".

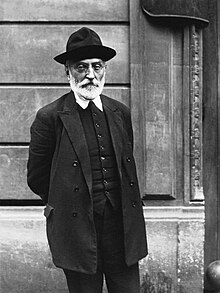

After his resignation, he left Spain —passing through Barcelona where he met with his friend Captain General Emilio Barrera, to whom, as Eduardo Aunós revealed fourteen years later, he proposed him to lead a coup d'état, which he refused—[237][238] and shortly afterwards he died at the Pont Royal Hotel in Paris.

[213][239][240][241] According to Ángeles Barrio Alonso,[242]The feeling of frustration and abandonment that Primo de Rivera must have felt when, after his forced resignation in January 1930, he moved to Paris, probably accelerated his death, which took place two months later in complete solitude.