Famine in India

Indian agriculture is heavily dependent on climate: a favorable southwest summer monsoon is critical in securing water for irrigating crops.

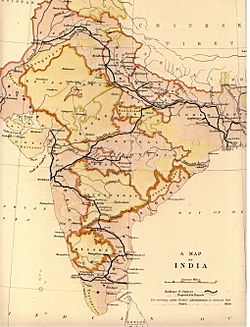

[5] Railroads built for the commercial goal of exporting food grains and other agricultural commodities only served to exacerbate economic conditions in times of famine.

[13] The Tughlaq Dynasty under Muhammad bin Tughluq held power during the famine centered on Delhi in 1335–1342 (which is reported to have killed thousands).

[19] Saint Gairbdas Ji has also described about this great famine in his Amar Granth Sahib that even Princes of Delhi had to struggle for food.

A major famine coincided with Lord Curzon's time as viceroy which affected large parts of India and killed at least 1 million people.

[38] Nightingale pointed out that money needed to combat famine was being diverted towards activities like paying for the British military effort in Afghanistan in 1878–80.

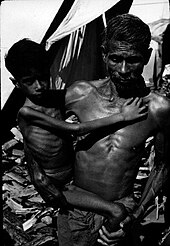

[fn 3] Mike Davis regards the famines of the 1870s and 1890s as 'Late Victorian Holocausts' in which the effects of widespread weather-induced crop failures were greatly aggravated by the negligent response of the British administration.

They died in the golden age of Liberal Capitalism; indeed, many were murdered ... by the theological application of the sacred principles of Smith, Bentham and Mill."

[47] The construction of Indian railways between 1860 and 1920, and the opportunities thereby offered for greater profit in other markets, allowed farmers to accumulate assets that could then be drawn upon during times of scarcity.

[48] Similarly, Donald Attwood writes that by the end of the 19th century 'local food scarcities in any given district and season were increasingly smoothed out by the invisible hand of the market[49] and that 'By 1920, large-scale institutions integrated this region into an industrial and globalizing world-ending famine and causing a rapid decline in mortality rates, hence a rise in human welfare'.

He points out that the subcontinent was free of famine between the 1900s and 1943, partly due to the railway and other improved communications, "although the shift in ideology away from hard-line Malthusianism towards a focus on saving lives also mattered."

[57][58] According to Mike Davis, export crops displaced millions of acres that could have been used for domestic subsistence and increased the vulnerability of Indians to food crises.

[57] Martin Ravallion dispute that exports were a major cause of the famine, pointing out that trade did have a stabilizing influence on India's food consumption, albeit a small one.

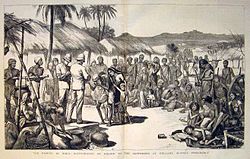

"[76] The Lt.-Governor of Bengal, Sir Richard Temple, successfully intervened in the Bihar famine of 1874 with little to no mortality; this is the only known example of adequate measures meeting a food crisis by the British.

Davis[97] notes that, "The newly constructed railroads, lauded as institutional safeguards against famine, were instead used by merchants to ship grain inventories from outlying drought-stricken districts to central depots for hoarding (as well as protection from rioters)" and that telegraphs served to coordinate a rise in prices so that "food prices soared out of the reach of outcaste laborers, displaced weavers, sharecroppers, and poor peasants."

Members of the British administrative apparatus were also concerned that the larger market created by railway transport encouraged poor peasants to sell off their reserve stocks of grain.

The 1880 Famine Codes urged a restructuring and massive expansion of railways, with an emphasis on intra-Indian lines as opposed to the existing port-centered system.

[101] On the other hand, railways also had a separate impact on reducing famine mortality by taking people to areas where food was available, or even out of India.

By generating broader areas of labor migration and facilitating the massive emigration of Indians during the late 19th century, they provided famine-afflicted people the option to leave for other parts of the country and the world.

Sen attributes this trend of decline or disappearance of famines after independence to a democratic system of governance and a free press—not to increased food production.

[116] A dought occurred in the state of Bihar in December 1966 on a much smaller scale and in which "Happily, aid was at hand and there were relatively fewer deaths".

In independent India, policy changes aimed to make people self-reliant to earn their livelihood and by providing food through the public distribution system at discounted rates.

Since the time of Mahabharata, people in several regions of India have associated spikes in rat populations and famine with bamboo flowering.

With the changing weather and onset of rains, the seeds germinate and force the mice to migrate to land farms in search of food.

[133] Similar beliefs have been observed in south India in the people of Cherthala in the Alappuzha district of Kerala who associate flowering bamboo with an impending explosion in the rat population.

The rise in prices of food grains caused migration and starvation, but the public distribution system, relief measures by the government, and voluntary organizations limited the impact.

The relief measures undertaken by the Government of Maharashtra included employment, programs aimed at creating productive assets such as tree plantation, conservation of soil, excavation of canals, and building artificial lentic water bodies.

The relief works initiated by the government helped employ over 5 million people at the height of the drought in Maharashtra leading to effective famine prevention.

[150] Growing export prices, the melting of the Himalayan glaciers due to global warming, changes in rainfall, and temperatures are issues affecting India.

[fn 10] However, Shiva warned in 2002 that famines are making a comeback and government inaction would mean they would reach the scale seen in the Horn of Africa in three or four years.