Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

Nonetheless, in a Japan that was turning away from its own past, he almost singlehandedly managed to push the traditional Japanese woodblock print to a new level, before it effectively died with him.

Kuniyoshi emphasized drawing from real life, which was unusual in Japanese training because the artist's goal was to communicate the essence of the subject matter rather than to furnish a literal representation of it.

Yoshitoshi also learned the elements of western drawing techniques and perspective through studying Kuniyoshi's collection of foreign prints and engravings.

These themes were partly inspired by the death of Yoshitoshi's father in 1863 and by the lawlessness and violence of the Japan surrounding him, which was simultaneously experiencing the breakdown of the feudal system imposed by the Tokugawa shogunate, as well as the effect of contact with Westerners.

In late 1863, Yoshitoshi began making violent sketches, eventually incorporated into battle prints designed in a bloody and extravagant style.

The public was attracted to Yoshitoshi's work not only for his superior composition and draftsmanship, but also his passion and intense involvement with his subject matter.

It is said that Yoshitoshi's work of the "bloody" period has influenced writers such as Jun'ichirō Tanizaki (1886–1965) as well as artists including Tadanori Yokoo and Masami Teraoka.

These were woodblock prints designed as full-page illustrations to accompany articles, usually on lurid and sensationalized subjects such as "true crime" stories.

With the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877, in which the old feudal order made one last attempt to stop the new Japan, newspaper circulation soared, and woodblock artists were in demand, with Yoshitoshi earning much attention.

In late 1877, he took up with a new mistress, the geisha Oraku; like Okoto, she sold her clothes and possessions to support him, and when they separated after a year, she too hired herself out to a brothel.

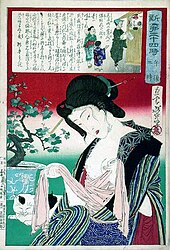

A series of bijin-ga designed in 1878 entitled Bijin shichi yoka caused political trouble for Yoshitoshi because it depicted seven female attendants to the Imperial court and identified them by name.

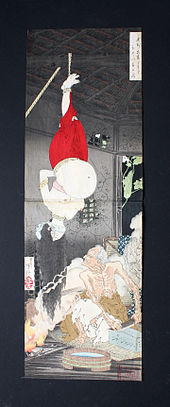

[5] This macabre work is iconic in its own right and influential in the history of modern kinbaku, in that Itoh Seiu was fascinated by Yoshitoshi's accurate depiction of sakasa zuri (upside down suspension).

An 1885 issue of the art and fashion magazine "Tokyo Hayari Hosomiki" ranked Yoshitoshi as the number-one ukiyo-e artist, ahead of his Meiji contemporaries such as Utagawa Yoshiiku and Toyohara Kunichika.

His last years were among his most productive, with his great series One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (1885–1892), and New Forms of Thirty-Six Ghosts (1889–1892), as well as some masterful triptychs of kabuki theatre actors and scenes.

A stone memorial monument to Yoshitoshi was built in Mukojima Hyakkaen garden, Tokyo, in 1898. holding back the night with its increasing brilliance the summer moon During his life he produced many series of prints, and a large number of triptychs, many of great merit.

Other less-common series also contain many fine prints, including Famous Generals of Japan, A Collection of Desires, New Selection of Eastern Brocade Pictures, and Lives of Modern People.

However, starting in the 1970s, interest in him resumed, and reappraisal of his work has shown the quality, originality and genius of the best of it, and the degree to which he succeeded in keeping the best of the old Japanese woodblock print, while pushing the field forward by incorporating both new ideas from the West, as well as his own innovations.

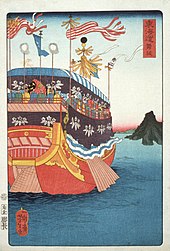

Yoshitoshi's series Mirror of Famous Generals of Great Japan consists of fifty-one woodblocks, published in his middle years, between 1877 -1882.