Military history of the Mali Empire

[4] Historical researchers also claim the technical reason for the empire's rapid expansion was supported by the strong blacksmith and metallurgy culture of Manden.

The blacksmith's activity helped the warriors by smithing fine weapons made of metals, as well as extending the boundaries of their empire by moving further and further afield in search of wood to sustain their industry.

[8] These "slaves" were actually high nobles dedicated to serve Mali by bringing the bow or quiver (traditional symbols of military force) to bear against the emperor's enemies.

With control of trade routes from the Savannah to North Africa, the Mandekalu were able to build up a standing cavalry of around 10,000 horsemen by the reign of Mansa Musa.

By the time Ibn Battuta visited the Mali Empire during the reign of Mansa Suleyman, an elite corps among the military was present at court.

The farima, like all farari, reported directly to the mansa who went out of his way to lavish awards on him in the form of special trousers (the wider the seat, the higher the merit) and gold anklets.

[27] The farimba could take over the court if he judged the vassal lord to be out of step with the mansa's wishes, and he kept a small army garrisoned inside the provincial capital for just such an occasion.

[34] The role of the sofa in Malian warfare changed dramatically after the reign of Sundjata from mere baggage handler to full-fledged warriors.

[18] So though imperial Mali was initially a horon-run army, its reliance on jonow as administrators (farimba) and officers (dùùkùnàsi) gradually transformed the character of its military.

Mari Djata utilized the infantry resources of his allies within and outside of Manden proper to best the Sosso in several confrontations, culminating in the Battle of Krina circa 1235.

Oral historians recount the use of poison bowmen from the south in Do (along what is now the Sankarani River), fire archers from Wagadou to the north, and heavy cavalry from the northern state of Mema.

After Djata's victory at Kirina, the Mandekalu forces quickly moved on to take the rest of the Sosso areas left leaderless upon Soumaoro's disappearance.

Tiramakhan, also known as Tiramaghan, of the Traore clan, was ordered by Sonjata to bring an army west after the king of Jolof had allowed horses to be stolen from Mandekalu merchants.

[40] The new western portion of the empire settlement would become an outpost that encompassed not only northern Guinea-Bissau but the Gambia and the Casamance region of Senegal (named for the Mandinka province of Casa or Cassa ruled by the Casa-Mansa).

The Traore clan left a large imprint on Guinea-Bissau and future settlements along the Gambia which trace their noble bloodlines back to him or other Mandekalu warriors.

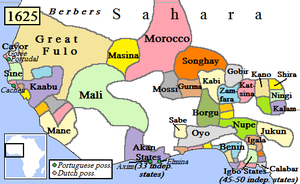

[43] The empire also conquered the city of Gao, epicenter of the burgeoning Songhai state, and brought Timbuktu and Jenne into its ambit if not its actual control.

Though his ascension meant an end to the destructive civil war, the Mali Empire was weaker than at any time since the rise of Mansa Djata.

[53] The Mali Empire has enjoyed virtually no military reverses in its first century of existence and had grown at a terrific rate in both size and wealth by the time Ibn Battuta arrived there.

The Wolof inhabitants of this kingdom united under their own emperor and formed the Jolof Empire around 1360 during a succession crisis that followed the death of Mansa Suleyman.

[55] It is unknown exactly why the Wolof broke away, but the destructive reign of Suleyman's predecessor and nephew Maghan I may have played a role in Jolof's motives if not the very reason why future mansas could not do anything about it.

[2] Attempts to re-conquer the Songhai were likely doomed due to the inhabitants being under Mandinka military influence for so long and being ruled by a dynasty that had its very roots in Mali's imperial court.

[66] The Mali Empire loss almost all access to the Saharan trade routes without which it could not get enough horses to take the centers back or preserve its own precarious position.

Using caravels to launch slave raids on coastal inhabitants,[68] the Malian vassal territories were caught off guard by both vessels and the raiders within them.

[69] While the coastal threat had been abated, an even more dangerous problem arrived on the empire's northern and eastern frontier in the form of an imperial Songhai state under the leadership of Sonni Ali.

In 1465, Songhai forces under Sulaiman Dama (also known as Sonni Silman Dandi)[70] attacked the province of Mema, which had seceded from Mali in the first few decades of the 15th century.

[73] The Songhay proved tougher customers and handed Yatenga's King Nasere a crushing defeat in 1483 effectively ending Mossi incursions in the Niger valley.

[72] Mali was powerless in the north, and its economic, military and political concentration shifted further west in the face of seemingly unstoppable Songhay aggression.

[80] Upon the advice of his brother Askiya Ishaq, Dawud did not chase the mansa's smaller force into the mountains and hills and instead bivouacked in the city for some seven days.

[74] Following Songhai's defeat by a Moroccan invasion in 1591 at the Battle of Tondibi, the Mali Empire was released from a century's-old pressure on its northern frontier.

In place of the Songhai Empire succeeded a much weaker authority on the Niger in the form of the Arma, separated from Mali by warring chiefdoms.