Trans-Saharan trade

Remarkable rock paintings (dated 3500 to 2500 BCE) in arid regions portray flora and fauna that are not present in the modern desert.

As Fernand Braudel points out, crossing such a zone, especially without mechanized transport, is worthwhile only when exceptional circumstances cause the expected gain to outweigh the cost and the danger.

In the mid-14th century CE, Ibn Battuta crossed the desert from Sijilmasa via the salt mines at Taghaza to the oasis of Oualata.

Predynastic Egyptians in the Naqada I period traded with Nubia to the south, the oases of the Western Desert to the west, and the cultures of the eastern Mediterranean to the east.

[8] The overland route through the Wadi Hammamat from the Nile to the Red Sea was known as early as predynastic times;[9] drawings depicting Egyptian reed boats have been found along the path dating to 4000 BCE.

It became a major route from Thebes to the Red Sea port of Elim, where travelers then moved on to either Asia, Arabia or the Horn of Africa.

[citation needed] Records exist documenting knowledge of the route among Senusret I, Seti, Ramesses IV and also, later, the Roman Empire, especially for mining.

[11] Later, Ancient Romans would protect the route by lining it with varied forts and small outposts, some guarding large settlements complete with cultivation.

From Kobbei, 40 kilometres (25 mi) north of al-Fashir, the route passed through the desert to Bir Natrum, another oasis and salt mine, to Wadi Howar before proceeding to Egypt.

One early 20th century researcher wrote of the Tripoli-Murzuk-Lake Chad route, "Most of the [trans-Saharan] traffic from the Mediterranean coast during the last 2,000 years has passed along this road.

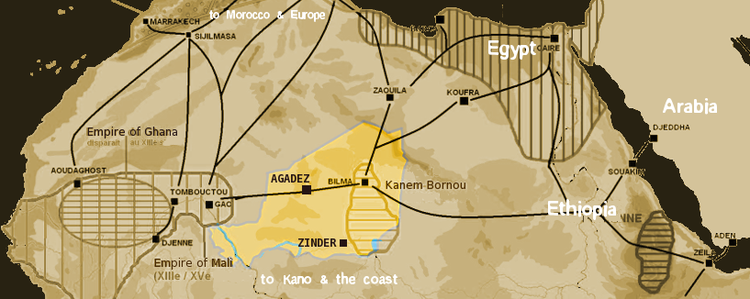

[15] The western routes were the Walata Road past present-day Oualata, Mauritania, from the Sénégal River, and the Taghaza Trail, from the Niger River, past the salt mines of Taghaza, north to the great trading center of Sijilmasa, situated in Morocco just north of the desert.

[13] The growth of the city of Aoudaghost, founded in the 5th century BCE, was stimulated by its position at the southern end of a trans-Saharan trade route.

From their capital of Germa in the Wadi Ajal, the Garamantean Empire raided north to the sea and south into the Sahel.

[13] Shillington states that existing contact with the Mediterranean received added incentive with the growth of the port city of Carthage.

Although there are Classical references to direct travel from the Mediterranean to West Africa (Daniels, p. 22f), most of this trade was conducted through middlemen, inhabiting the area and aware of passages through the drying lands.

However, it has been argued that no horse skeletons have been found dating from this early period in the region, and chariots would have been unlikely vehicles for trading purposes due to their small capacity.

Further east of the Fezzan with its trade route through the valley of Kaouar to Lake Chad, Libya was impassable due to its lack of oases and fierce sandstorms.

There, and in other North African cities, Berber traders had increased contact with Islam, encouraging conversions, and by the 8th century, Muslims were traveling to Ghana.

Around 1050, Ghana lost Aoudaghost to the Almoravids, but new goldmines around Bure reduced trade through the city, instead benefiting the Malinke of the south, who later founded the Mali Empire.

[27] The rise of the Ghana Empire, in what is now Mali, Senegal, and southern Mauritania, accompanied the increase in trans-Saharan trade.

[vague] North Africa had declined in both political and economic importance, while the Saharan crossing remained long and treacherous.

In a major military expedition organized by the Saadian sultan Ahmad al-Mansur, Morocco sent troops across the Sahara and attacked Timbuktu, Gao and some other important trading centres, destroying buildings and property and exiling prominent citizens.

But trade routes to the West African coast became increasingly easy, particularly after the French invasion of the Sahel in the 1890s and subsequent construction of railways to the interior.

[35] The route is paved except for a 120 mi (200 km) section in northern Niger, but border restrictions still hamper traffic.