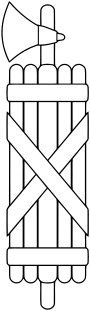

Fasces

The fasces frequently occurs as a charge in heraldry: it is present on the reverse of the U.S. Mercury dime coin and behind the podium in the United States House of Representatives and in the Seal of the U.S. Senate; and it was the origin of the name of the National Fascist Party in Italy (from which the term fascism is derived).

During the first half of the twentieth century, both the fasces and the swastika (each symbol having its own unique ancient religious and mythological associations) became heavily identified with the fascist political movements of Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler.

The fasces remained in use in many societies after World War II because it had already been adopted and incorporated into the iconography of numerous governments outside Italy, prior to Mussolini.

In contrast, the swastika remains in common usage only in Asia, where it originated as an ancient Hindu symbol, and in Navajo iconography, where its religious significance is entirely unrelated to, and predates, early 20th-century European fascism.

In ancient Rome, the bundle was a material symbol of a Roman magistrate's full civil and military power, known as imperium.

[7] In common language and literature, the fasces were regularly associated with certain offices: praetors were referred to in Greek as the hexapelekys (lit.

By the Renaissance, there emerged a conflation of the fasces with a Greek fable first recorded by Babrius in the second century AD depicting how individual sticks can be easily broken but how a bundle could not be.

[14] The earliest archaeological remains of a fasces are those discovered in a necropolis near the Etruscan hamlet now called Vetulonia by the archaeologist Isidoro Falchi in 1897.

[16] An Etruscan origin, furthermore, is supported by ancient literary evidence: the poet Silius Italicus, who flourished in the late 1st century AD, posited that Rome adopted many of its emblems of office – viz the fasces, the curule chair, and the toga praetexta – specifically from Vetulonia.

Macrobius, writing in the 5th century AD, have the Romans taking fasces from the Etruscans as spoils of war rather than adopted by cultural diffusion.

[21] Plutarch, in his Life of Publicola, describes an incident in which Lucius Junius Brutus, the first Roman consul, has lictors scourge with rods and decapitate with axes – components of the fasces – his own sons who were conspiring to restore the Tarquins to the throne.

[29] Within the pomerium, Rome's sacred city boundary, the magistrates normally removed the axes from their fasces to symbolise the appealable nature of their civic powers.

The laurels decorating the triumphator's axed fasces were removed and decided in a ceremony, placing them in the lap of the cult statue of the Capitoline Jupiter.

[39] At the death of the first emperor, Augustus, in AD 14, his widow Livia was voted a lictor by the Senate, though sources disagree as to whether she ever exercised the privilege.

[43] This later form persisted through to the Eastern Roman Empire: the Byzantine antiquarian, John the Lydian, writing in the sixth century AD described fasces as "long rods evenly bound together" with red straps and axes held aloft.

[46] For example, c. 1439, Jean de Rovroy, when translating Frontinus' Stratagems, was deceived by a false cognate and thought fasces referred to ribbons Roman magistrates would wear on their heads; such misconceptions were apparently common, and dated back to the 11th century.

[47] Renaissance humanists, especially those who read more Latin, however, quickly became well-informed on fasces and their legal technicalities, including the customary removal of axes within the city, lowering before the people, and alternation by the consuls.

[50] Pope Clement VIII's reassertion of Papal juridical authority after the sack of Rome in 1527 started iconographic developments that would associate fasces with personifications of Justice.

Antje Middeldorf-Kosegarten, in Reallexikon zur Deutschen Kunstgeschichte, charts for the post-Ripa period [after 1603] a proliferation of the fasces as symbol across almost every conceivable visual medium, from architectural sculpture to decorative arts, in paintings of every type, on monuments that range from honorific arches to tombs, as well as in medallic art and engravings...[55] By the mid-seventeenth century, fasces had become "well established throughout Europe as a catch-all symbol for stable and competent governance".

[59] There, during the American Revolution, the fasces' symbology as referencing strength through unity was adopted as a symbol of the united colonial effort against British rule.

[61] Topped with a Phrygian cap, fasces were seen as a reference to the "imagined spirit of the early Roman republic [and] its assertion of ideals of liberty and justice against tyranny".

: fasci), etymologically related to fasces, was used by various political organizations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with the figurative meaning of "league" or "union".

A review of the images included in Les Grands Palais de France : Fontainebleau[66][67] reveals that French architects used the Roman fasces (faisceaux romains) as a decorative device as early as the reign of Louis XIII (1610–1643) and continued to employ it through the periods of Napoleon I's Empire (1804–1815).

The fasces appears on the helmet and the buckle insignia of the French Army's Autonomous Corps of Military Justice, as well as on that service's distinct cap badges for the prosecuting and defending lawyers in a court-martial.