Fatimid art

The period was marked by a prosperity amongst the upper echelons, manifested in the creation of opulent and finely wrought objects in the decorative arts, including carved rock crystal, lustreware and other ceramics, wood and ivory carving, gold jewelry and other metalware, textiles, books and coinage.

[1]: 200 The libraries were largely destroyed and precious gold objects were melted down, with a few of the treasures dispersed across the medieval Christian world.

Made in Egypt in the late 10th century, the ewer pictured is exquisitely decorated with fantastic birds, beasts and twisting tendrils.

Great skill was required to hollow out the raw rock crystal without breaking it and to carve the delicate, often very shallow, decoration.

The Fatimids produced a variety of beautifully crafted works of art resulting in textiles, ceramics, woodwork, jewelry, and importantly, rock crystals.

The last one to surface on the market was purchased by the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1862.”[3] The treasury of the Basilica of San Marco in Venice has two ewers.

[4] “The extant rock crystal objects with no identifying inscription on them appear to be types of containers, either goblets for drinking or ewers and basins for holding liquids, perhaps for washing the hands of the guests after a meal.

Between the tenth and eleventh centuries, Egypt produced most of the rock crystals that were located in the medieval treasuries of the West.

"All of the details are drilled and cut with great skill, including the texturing in the form of lines and dots covering the bird and animal and the leaves of the arabesque patterns.

This unusual shape can be explained in part by the material from which they were made: the high price of rock crystal and the proficiency required of the carver meant that the manufacture of these precious objects was only patronized by royalty or nobility.”[6] The lamp from Saint Petersburg goes back to the boat-shaped early Christian metal lamps.

[11] The prevalence of books within the Fatimid empire was demonstrated by the existence of the Dār al-’Ilm, or the House of Knowledge.

When the Fatimid Dynasty dissolved during the twelfth century, the libraries and collections of books that existed in Cairo were dispersed, making it difficult to locate any complete manuscripts.

It is rare to have an example of both text and illustrations of the same page, which makes it difficult to gather information about illuminated manuscripts.

While it is unclear whether this page originated in a book, potentially of scientific or zoological subject matter, it is an example of larger patterns of naturalist and figural representation within Fatimid art.

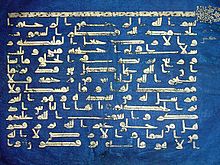

[16] Each horizontal indigo parchment leaf is marked by fifteen lines of gold Kufic script that are of the same length; ends of the verses are decorated with silver medallions, besides which there are no additional ornamentations.

Alain George of University of Edinburgh claimed that the script had been written with gold powder as an ink pigment, a technique called chrysography.

The calligrapher was more likely to first write the text with a pen charged with transparent adhesive, apply gold leaf, and then brush off the fragments that didn’t stick to the page.

As plausible as the attributions are, scholars still lack strong evidence to anchor the book's origin and time period.

It was copied by al-Husayn ibn Abdallah and is estimated to have been produced in Cairo, Egypt in 1028, made with valuable materials such as gold, color, and ink on paper.

In 1062, a connection between Fatimid and Yemeni rulers was made in order to strengthen religious and political power, as well as to gain access trade routes to the Indian Ocean and Red Sea.

This manuscript was exchanged in order for the Fatimid Caliph al-Mustansir bi’llah to demonstrate his wealth, and political and religious power to the Yemeni ruler Ali al-Sulayhi.

With this example, it is easier to understand the difficulty of locating Fatimid book materials and why so few remain intact and identifiable.

The combination of gold filigree with beaded granulation ("grain") creates an almost sculptural effect, thus giving the surfaces of the case a three-dimensional quality.

[22] Besides elaborately decorated books, government documents are valuable sources that could offer us profound insight into the polities of Medieval Middle East.

Large amount Fatimid documents discovered in the Cairo Geniza challenge this widely-accepted yet false notion.

The state documents included petitions to sovereigns, memoranda to high-ranking officials, fiscal records, taxes receipts, accounts, ledgers, and decrees.

[23] The comprehensiveness and abundance of the documents allow scholars to re-construct the statecraft of the Fatimid Caliphate that probably situated between the two extreme types of polities - indifference and authoritarianism.

The juxtaposition of Fatimid decrees and Hebrew script indicates that the documents were most likely to be recycled as scrap papers by cantors working at the synagogue.

The rest of the scroll was filled with text in a Kufic script that contained Quranic verses, incantations, and prayers.