Federalist Era

The first Congress also passed the United States Bill of Rights, a key demand of Anti-Federalists, to constitutionally limit the powers of the federal government.

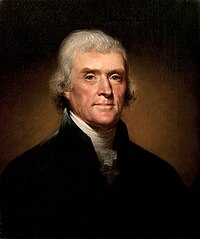

Jefferson feared that Hamilton's policies would lead to an aristocratic, and potentially monarchical, society that clashed with his vision of a republic built on yeomen farmers.

This economic policy debate was further roiled by the French Revolutionary Wars, as Jeffersonians tended to sympathize with France and Hamiltonians with Britain.

In the wake of these foreign policy tensions, the Federalists imposed the Alien and Sedition Acts to crack down on dissidents and make it more difficult for immigrants to become citizens.

Jefferson's egalitarian vision appealed to farmers and middle-class urbanites alike and the party embraced campaign tactics that mobilized all classes of society.

The Anti-Federalist movement opposed the draft Constitution primarily because it lacked a bill of rights, which the Federalists eventually agreed to add in an effort to gain support from the states for ratification.

The major stumbling block for the Anti-Federalists, according to Elkins and McKitrick's The Age of Federalism, was that the supporters of the Constitution had been more deeply committed, had cared more, and had outmaneuvered the less energetic opposition.

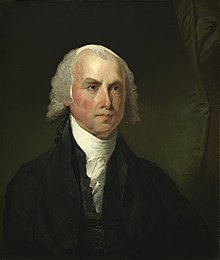

[8] Congressman James Madison, who had been a prominent advocate of the Constitution's ratification, introduced a series of amendments that would become known as the United States Bill of Rights.

There were both domestic and foreign Revolutionary War-related debts, as well as a trade imbalance with Great Britain that was crippling American industries and draining the nation of its currency.

In September 1789, with no resolution in sight and the close of that session drawing near, Congress directed Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton to prepare a report on credit.

Hamilton believed that these measures would restore the ailing economy, ensure a stable and adequate money stock, and make it easier for the federal government to borrow during emergencies such as wars.

Hamilton's proposed national bank would provide credit to fledgling industries, serve as a depository for government funds, and oversee one nationwide currency.

[27] In December 1791, Hamilton published the Report on Manufactures, which recommended numerous policies designed to protect U.S. merchants and industries in order to increase national wealth, induce artisans to immigrate, cause machinery to be invented, and employ women and children.

Led by Revolutionary War veteran John Fries, rural German-speaking farmers protested what they saw as a threat to their republican liberties and to their churches.

The rebellion, the deployment of the army, and the results of the trials alienated many in Pennsylvania and other states from the Federalist Party, damaging Adams's re-election hopes.

[54] Native American resistance to Wayne's army quickly collapsed following the battle,[54] and delegates from the various confederation tribes gathered for a peace conference at Fort Greene Ville in June 1795.

Acting aggressively, Genêt outfitted privateers that sailed with American crews under a French flag and attacked British shipping.

[62] Washington sent John Jay to Britain to resolve numerous difficulties, some leftover from the Treaty of Paris and some having arisen during the French Revolutionary Wars.

In addition, America hoped to open markets in the British Caribbean and end disputes stemming from the naval war between Britain and France.

As a neutral party, the United States argued, it had the right to carry goods anywhere it wanted, but the British seized American ships that traded with the French.

[65] They denounced the Jay Treaty as an insult to American prestige, a repudiation of the French alliance of 1777, and a severe shock to Southern planters who owed those old debts, and who were never to collect for the lost slaves the British captured.

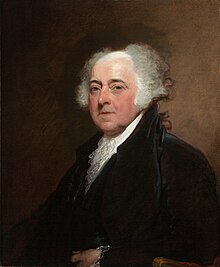

[74] President Adams hoped to maintain friendly relations with France, and after taking office he sent a delegation to Paris asking for compensation for the French attacks on American shipping.

In light of the threat of invasion from the more powerful French forces, Adams asked Congress to authorize the creation of a twenty-five thousand man Army and a major expansion of the Navy.

[79] In February 1799, Adams surprised the nation by announcing that he would send a peace mission to France headed by diplomat William Vans Murray.

[85] A key factor in the uproar surrounding the Alien and Sedition Acts was that the very concept of seditious libel was flatly incompatible with party politics.

Historian Stephen Kurtz has argued:[87] With the Federalist Party deeply split over his negotiations with France, and the opposition Republicans enraged over the Alien and Sedition Acts and the expansion of the military, Adams faced a daunting reelection campaign in 1800.

[93] Historian John E. Ferling attributes Adams' defeat to five factors: the stronger organization of the Democratic-Republicans; Federalist disunity; the controversy surrounding the Alien and Sedition Acts; the popularity of Jefferson in the south; and, the effective politicking of Aaron Burr in New York.

Jefferson's refusal to call for a complete replacement of federal appointees under the spoils system was followed by his successors until the election of Andrew Jackson in 1828.

Some younger Federalist leaders tried to emulate the Democratic-Republican tactics, but their overall disdain of democracy along with the upper class bias of the party leadership eroded public support.

As Adams filled these new positions during the final days of his presidency, opposition newspapers and politicians soon began referring to the appointees as "midnight judges."