1800 United States presidential election

John Adams Federalist Thomas Jefferson Democratic-Republican Presidential elections were held in the United States from October 31 to December 3, 1800.

The Democratic-Republicans also denounced the Alien and Sedition Acts, which the Federalists had passed to make it harder for immigrants to become citizens and to restrict statements critical of the federal government.

The Democratic-Republicans were well organized at the state and local levels, while the Federalists were disorganized and suffered a bitter split between their two major leaders, Adams and Alexander Hamilton.

According to historian John Ferling, the jockeying for electoral votes, regional divisions, and the propaganda smear campaigns created by both parties made the election recognizably modern.

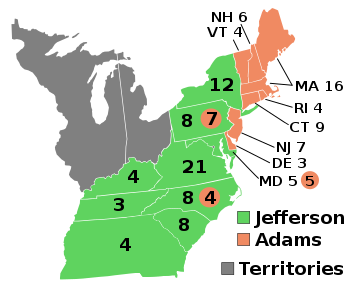

The Federalists swept New England, the Democratic-Republicans dominated the South, and the parties split the Mid-Atlantic states of New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania.

The Federalists nominated a ticket consisting of incumbent President John Adams of Massachusetts and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina.

The Democratic-Republicans nominated a ticket consisting of Vice President Thomas Jefferson of Virginia and former Senator Aaron Burr of New York.

Jefferson had been the runner-up in the previous election and had co-founded the party with James Madison and others, while Burr was popular in the electorally important state of New York.

On top of this, the election pitted the "larger than life" Adams and Jefferson, who were formerly close allies turned political enemies.

In 1798, George Washington had complained "that you could as soon scrub the blackamoor white, as to change the principles of a professed Democrat; and that he will leave nothing unattempted to overturn the Government of this Country".

[8] Meanwhile, the Democratic-Republicans accused Federalists of subverting republican principles with the Alien and Sedition Acts, some of which were later declared unconstitutional after their expiration by the Supreme Court, and relying for their support on foreign immigrants[clarification needed]; they also accused Federalists of favoring Britain and the other coalition countries in their war with France in order to promote aristocratic, anti-democratic values.

[9] Adams was attacked by both the opposition Democratic-Republicans and a group of so-called "High Federalists" aligned with Alexander Hamilton.

The Democratic-Republicans felt that the Adams foreign policy was too favorable toward Britain; feared that the new army called up for the Quasi-War would oppress the people; opposed new taxes to pay for war; and attacked the Alien and Sedition Acts as violations of states' rights and the Constitution.

During Washington's presidency, Hamilton had been able to influence the federal response to the Whiskey Rebellion (which threatened the government's power to tax citizens).

However, Hamilton's plan backfired and hurt the Federalist party, particularly after one of his letters, a scathing criticism of Adams that was fifty-four pages long,[13] fell into the hands of a Democratic-Republican and soon after became public.

[14] Yet, throughout this entire process, the candidates themselves were conspicuously missing from the campaigning, at least publicly, due to fears that they may otherwise be tagged as "demagogues".

In March 1800, two months before the assembly elections, the Democratic-Republicans attempted to pass a bill that would switch from a legislature vote to electoral districts, hoping they would secure at least a third of the state's seats.

[19] In response to the Federalist defeat, Hamilton attempted to get Governor John Jay to call a special session of the outgoing Federalist-dominated New York legislature.

The state elections in mid-October had produced an assembly that was about evenly divided between committed Federalists and Republicans, with 16 unaffiliated representatives who were all strongly pro-Jefferson.

The Federalists therefore arranged for one of their Rhode Island electors to vote for John Jay instead of Charles Pinckney to prevent the election from resulting in a tie.

[30][31] If the Georgia ballots had been rejected based on these supposed irregularities, Jefferson and Burr would have been left with 69 votes each, or one short of the 70 votes required for a majority, meaning a contingent election would have been required between the top five finishers (Jefferson, Burr, incumbent president John Adams, Charles C. Pinckney, and John Jay) in the House of Representatives.

[32] Brewer's arguments helped to influence Vice President Pence's decision to reject the theory that he had such powers, via Judge J. Michael Luttig.

Of the 155 counties and independent cities making returns, Jefferson and Burr won in 115 (74.19%), whereas the Adams ticket carried 40 (25.81%).

Of the 16 states that took part in the 1800 election, six (Kentucky, Maryland, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Tennessee, and Virginia) used some kind of popular vote.

In Rhode Island and Virginia, voters elected their state's entire Electoral College delegation at large; Kentucky, Maryland, North Carolina, and Tennessee all used some variation of single-member districts.

Newspapers are also the main source of voting records in the early 19th century, and frontier states such as Tennessee had few in operation, without any known surviving examples.

[83][page needed] He urged the Federalists to support Jefferson because he was "by far not so dangerous a man" as Burr; in short, he would much rather have someone with wrong principles than someone devoid of any.

[13] From February 11 to 17, the House cast a total of 35 ballots; each time eight state delegations voted for Jefferson, one short of the necessary majority of nine.

The musical simplifies the complicated multiple elections somewhat, portraying Adams's unpopularity as making the real choice between Jefferson and Burr.

Historians wrote that Adams did not lose that badly in the original election, with the musical inflating the size of Jefferson's victory.