Louse-feeder

Typhus research involving human subjects, who were purposely infected with the disease, was also carried out in various Nazi concentration camps, in particular at Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen and to a lesser extent at Auschwitz.

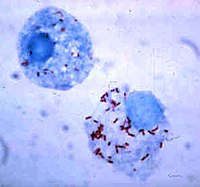

French bacteriologist Charles Nicolle showed in 1909 that lice (Pediculus humanus corporis) were the primary means by which the typhus bacteria (Rickettsia prowazekii) were spread.

[3] After Poland regained its independence, Weigl was hired in 1920 as a Professor of Biology at the Jan Kazimierz University in Lwów, at the Institute for Study of Typhus and Virology.

Once they matured, they were removed from the feeders, held down in a clamp machine especially designed by Weigl, and anally injected with the strain of the typhus bacteria.

[3] Other dangers that employment at the institute involved, in addition to the contraction of typhus, concerned allergic reactions to the vaccine or asthma attacks because of the louse feces dust.

Nevertheless, despite the official prohibition on employment, Weigl used his prestige and influence (during this time Nikita Khrushchev visited the institute) to secure the release of several Polish would-be deportees and in some cases managed to obtain permission for those who had already been exiled to return.

[3] These individuals were then given work in the institute as either nurses, interpreters (Weigl himself did not speak Russian)[3] or as some of the first lice feeders; people who were given the job as a means of protecting them from persecution by the Soviet authorities.

The Institute was made directly subordinate to the German military, which, as it turned out, ended up giving its workers significant protection against the Gestapo.

The Nazis converted a building of the former Queen Jadwiga Grammar School into Weigl's new laboratory and ordered that the production of the vaccine be stepped up, with the whole output being shipped to the German armed forces.

[6] Weigl managed to convince the occupation authorities to give him full discretion as to whom he hired for his experiments, even as he himself refused to sign the so-called Volksliste which would have identified him as an ethnic German (since he was of Austrian background) with access to privileges and opportunities unavailable to Poles.

[3] The group of scholars hired by Weigl were often brought in by Wacław Szybalski, an oncologist, who was also put in charge of supervising the lice feeding.

As a result, the workers of the institute, unlike other Poles in the city, could move freely about and, if stopped by the police or the Gestapo, were quickly released.

[3] In autumn of 1941, the mathematician Stefan Banach began working at the institute as a lice feeder,[6] as did his son, Stefan Jr.[5] Banach continued to work at the institute feeding lice until March 1944, and managed to survive the war as a result, unlike many other Polish mathematicians who were killed by the Nazis (although he died of lung cancer shortly after the war's conclusion).

Banach's employment at the institute also gave protection to his wife, Łucja (it was she who purchased the notebook that eventually became the Scottish Book), who was in particular danger because of her Jewish background.

[3] Additionally, Weigl began employing members of the Polish anti-Nazi resistance, the Home Army, in his institute, which provided them with sufficient cover to carry out their underground activities.

Aleksander Szczęścikiewicz and Zygmunt Kleszczyński, two leaders of the underground scout movement, the Grey Ranks (Szare Szeregi), also worked at the institute.

However, Eisenberg believed that he could survive the war by hiding in Kraków, turned down Weigl's offer, and in 1942 was caught by the Nazis and sent to the Belzec extermination camp where he was murdered.