Warsaw Ghetto

At its height, as many as 460,000 Jews were imprisoned there,[5] in an area of 3.4 km2 (1.3 sq mi), with an average of 9.2 persons per room,[6][7] barely subsisting on meager food rations.

[2][9][10][11] Before World War II, the majority of Polish Jews lived in the merchant districts of Muranów, Powązki, and Stara Praga.

[12] Antisemitic legislation, boycotts of Jewish businesses, and the nationalist "endecja" post-Piłsudski Polish government plans put pressure on Jews in the city.

[15] By the end of the September campaign the number of Jews in and around the capital increased dramatically with thousands of refugees escaping the Polish-German front.

[18] The Nazi-appointed Jewish Council (Judenrat) in Warsaw, a committee of 24 people headed by Adam Czerniaków, was responsible for carrying out German orders.

"[19] Food stamps were introduced by the German authorities, and measures were stepped up to liquidate all Jewish communities in the vicinity of Warsaw intensified.

[20] The Nazi authorities expelled 113,000 ethnic Poles from the neighbourhood, and ordered the relocation of 138,000 Warsaw Jews from the suburbs into the city center.

German policemen from Battalion 61 used to hold victory parties on the days when a large number of prisoners were shot at the ghetto fence.

[26] The borders of the ghetto changed and its overall area was gradually reduced, as the captive population was decreased by outbreaks of infectious diseases, mass hunger, and regular executions.

[32] Like in all Nazi ghettos across occupied Poland, the Germans ascribed the internal administration to a Judenrat Council of the Jews, led by an "Ältester" (the Eldest).

Although his personality as president of the Warsaw Judenrat may not become as infamous as Chaim Rumkowski, Ältester of the Łódź Ghetto; the SS policies he had followed were systematically anti-Jewish.

— Lucy Dawidowicz, The War Against the Jews [33]The Council of Elders was supported internally by the Jewish Ghetto Police (Jüdischer Ordnungsdienst),[17] formed at the end of September 1940 with 3,000 men, instrumental in enforcing law and order as well as carrying out German ad hoc regulations, especially after 1941, when the number of refugees and expellees in Warsaw reached 150,000 or nearly one third of the entire Jewish population of the capital.

At that time, the parish priest, Marceli Godlewski who before the war was connected to Endecja and anti-Jewish actions, now became involved in helping Jews.

At the rectory of the parish, the priest sheltered and helped many escape, including Ludwik Hirszfeld, Louis-Christophe Zaleski-Zamenhof and Wanda Zamenhof-Zaleska.

This meager food supply by the German authorities usually consisted of dry bread, flour and potatoes of the lowest quality, groats, turnips, and a small monthly supplement of margarine, sugar, and meat.

[5] Men, women and children all took part in smuggling and illegal trade, and private workshops were created to manufacture goods to be sold secretly on the "Aryan" side of the city.

Foodstuffs were often smuggled by children alone, who crossed the ghetto wall by the hundreds in any way possible, sometimes several times a day, returning with goods that could weigh as much as they did.

[5] During the first year and a half, thousands of Polish Jews as well as some Romani people from smaller towns and the countryside were brought into the ghetto, but as many died from typhus and starvation the overall number of inhabitants stayed about the same.

[42] Facing an out-of-control famine and meager medical supplies, a group of Jewish doctors imprisoned in the ghetto decided to use the opportunity to study the physiological and psychological effects of hunger.

[47] These schools, operating under the guise of kindergartens, medical centers and soup kitchens, were a place of refuge for thousands of children and teens, and hundreds of teachers.

[50] Israel Gutman estimates that around 20,000 prisoners (out of more than 400,000) remained at the top of ghetto society, either because they were wealthy before the war, or because they were able to amass wealth during it (mainly through smuggling).

Those families and individuals frequented restaurants, clubs and cafes, showing in stark contrast the economic inequalities of ghetto life.

By spring 1942, the Stickerei Abteilung Division with headquarters at Nowolipie 44 Street had already employed 3,000 workers making shoes, leather products, sweaters and socks for the Wehrmacht.

[54] Some 15,000 Jews were working in the ghetto for Walter C. Többens from Hamburg, a convicted war criminal,[55] including at his factories on Prosta and Leszno Streets among other locations.

[62] The extermination of Jews by means of poisonous gases was carried out at Treblinka II under the auspices of Operation Reinhard, which also included Bełżec, Majdanek, and Sobibór death camps.

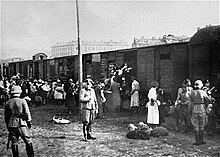

[59] About 254,000 Warsaw Ghetto inmates (or at least 300,000 by different accounts) were sent to Treblinka during the Grossaktion Warschau, and murdered there between Tisha B'Av (July 23) and Yom Kippur (September 21) of 1942.

[2] Meanwhile, between October 1942 and March 1943, Treblinka received transports of almost 20,000 foreign Jews from the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia via Theresienstadt, and from Bulgarian-occupied Thrace, Macedonia, and Pirot following an agreement with the Nazi-allied Bulgarian government.

[2] The underground activity of ghetto resistors in the group Oyneg Shabbos increased after learning that the transports for "resettlement" led to the mass killings.

The final assault started on the eve of Passover of April 19, 1943, when a Nazi force consisting of several thousand troops entered the ghetto.

According to the official report, at least 56,065 people were killed on the spot or deported to German Nazi concentration and death camps (Treblinka, Poniatowa, Majdanek and Trawniki).