Feminist economics

[4] Many scholars including Ester Boserup, Marianne Ferber, Drucilla K. Barker, Julie A. Nelson, Marilyn Waring, Nancy Folbre, Diane Elson, Barbara Bergmann and Ailsa McKay have contributed to feminist economics.

In 1970, Ester Boserup published Woman's Role in Economic Development and provided the first systematic examination of the gendered effects of agricultural transformation, industrialization and other structural changes.

This work, among others, laid the basis for the broad claim that "women and men weather the storm of macroeconomic shocks, neoliberal policies, and the forces of globalization in different ways.

The critique began in microeconomics of the household and labor markets and spread to macroeconomics and international trade, ultimately extending to all areas of traditional economic analysis.

[8] Feminist economists pushed for and produced gender aware theory and analysis, broadened the focus on economics and sought pluralism of methodology and research methods.

For example, Geoff Schneider and Jean Shackelford suggest that, as in other sciences,[19] "the issues that economists choose to study, the kinds of questions they ask, and the type of analysis undertaken all are a product of a belief system which is influenced by numerous factors, some of them ideological in character.

Amartya Sen argues that "the systematically inferior position of women inside and outside the household in many societies points to the necessity of treating gender as a force of its own in development analysis.

In recent works[33] Julie A. Nelson has shown how the idea that "women are more risk averse than men," a now-popular assertion from behavioral economics, actually rests on extremely thin empirical evidence.

[17] Feminist economists argue that people are more complex than such models, and call for "a more holistic vision of an economic actor, which includes group interactions and actions motivated by factors other than greed.

Feminist research in these areas contradicts the neoclassical description of labor markets in which occupations are chosen freely by individuals acting alone and out of their own free will.

This theory examines the role of institutions and evolutionary social processes in shaping economic behavior, emphasizing "the complexity of human motives and the importance of culture and relations of power."

[23] The work of George Akerlof and Janet Yellen on efficiency wages based on notions of fairness provides an example of a feminist model of economic actors.

[5] In other words, when feminist economists highlight the biases of mainstream economics, they focus on its social beliefs about masculinity like objectivity, separation, logical consistency, individual accomplishment, mathematics, abstraction, and lack of emotion, but not on the gender of authorities and subjects.

Feminist economists say that mainstream economics has been disproportionately developed by European-descended, heterosexual, middle and upper-middle-class men, and that this has led to suppression of the life experiences of the full diversity of the world's people, especially women, children and those in non-traditional families.

In response, she points to Mary Collier's works such as The Woman's Labour (1739) to help understand Smith's contemporaneous experiences of women and fill in such gaps.

This method of economic analysis seeks to overcome gender bias by showing how men and women differ in their consumption, investment or saving behavior.

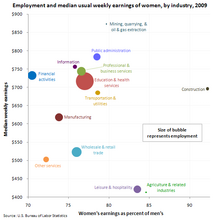

[41] This model highlights how gender effects macroeconomic variables and shows that economies have a higher likelihood of recovering from downturns if women participate in the labor force more, instead of devoting their time to housework.

Bernard Walters shows that traditional neoclassical models fail to adequately assess work related to reproduction by assuming that the population and labor are determined exogenously.

Aggregate income is not sufficient to evaluate general well-being, because individual entitlements and needs must also be considered, leading feminist economists to study health, longevity, access to property, education, and related factors.

[3][45] Bina Agarwal and Pradeep Panda illustrate that a woman's property status (such as owning a house or land) directly and significantly reduces her chances of experiencing domestic violence, while employment makes little difference.

[46] They argue that such immovable property increases women's self-esteem, economic security, and strengthens their fall-back positions, enhancing their options and bargaining clout.

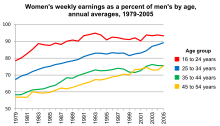

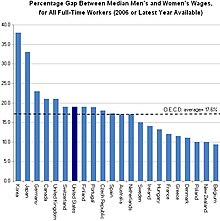

While conventional neoclassical economic theories of the 1960s and 1970s explained these as the result of free choices made by women and men who simply had different abilities or preferences, feminist economists pointed out the important roles played by stereotyping, sexism, patriarchal beliefs and institutions, sexual harassment, and discrimination.

For example, Lourdes Benería argues that economic development in the Global South depends in large part on improved reproductive rights, gender equitable laws on ownership and inheritance, and policies that are sensitive to the proportion of women in the informal economy.

[79] Additionally, Nalia Kabeer discusses the impacts of a social clause that would enforce global labor standards through international trade agreements, drawing on fieldwork from Bangladesh.

Such efforts, Bergeron highlights, allow women the chance to take control of economic conditions, increase their sense of individualism, and alter the pace and direction of globalization itself.

Suzanne Bergeron, for example, focuses on the typical theories of globalization as the "rapid integration of the world into one economic space" through the flow of goods, capital, and money, in order to show how they exclude some women and the disadvantaged.

First, she describes how feminists may de-emphasize the idea of the market as "a natural and unstoppable force," instead depicting the process of globalization as alterable and movable by individual economic actors including women.

[85] Cristina Carrasco and Arantxa Rodriquez examine the care economy in Spain to suggest that women's entrance into the labor market requires more equitable caregiving responsibilities.

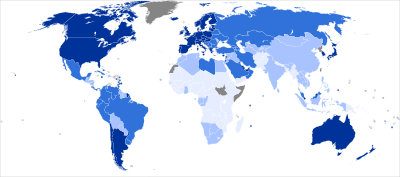

The HDI takes into account a broad array of measures beyond monetary considerations including life expectancy, literacy, education, and standards of living for all countries worldwide.

Through its analysis of the institutional sources of gender inequality in over 100 countries, SIGI has been proven to add new insights into outcomes for women, even when other factors such as religion and region of the world are controlled for.

|

Very High (developed country)

|

Low (developing country)

|

|

High (developing country)

|

Data unavailable

|

|

Medium (developing country)

|