Feminist pathways perspective

[7] While these attributions are characterized as crimes, research has also begun to conceptualize them as survival strategies to cope with victimization.

[8] It was not until the 1970s that research analyzed victimization, traumas, and past abuse as factors that can influence women to commit crimes.

[1][8] That said, the age and gendered patterns of victimization risk, context, and consequences are highly visible and exacerbated among incarcerated women.

[1] Literature suggests female offenders' victimization often begins at a young age and persists through her lifetime.

[11] Ninety-two percent of girls under 18 in the California juvenile justice system report having faced emotional, sexual, or physical abuse.

Eighty percent of women in prison in the United States have experienced an event of physical or sexual abuse in her lifetime.

[4] Life course researchers maintain that people are exposed to violence to various degrees based on their location, socioeconomic circumstance, and lifestyle choices.

[4][12] For instance, someone from a low-income neighborhood who spends time in public places at night and among strangers may be more likely to encounter offenders, and therefore at a greater risk of victimization.

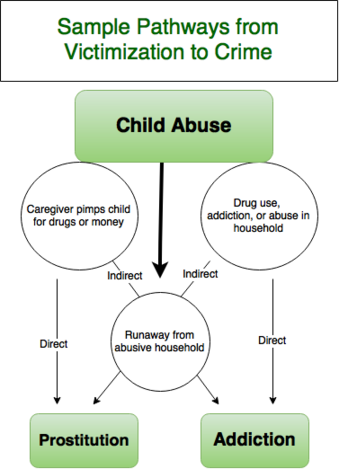

[4] Childhood is a critical period of growth, and child victims, according to the cycle of violence thesis, will be more likely to be involved in violent crime in the future.

Feminist criminologists argue that women adapt to traumas differently than men due to gender inequalities.

[7] Feminist criminologists understand childhood victimization as a structured theme throughout the lives of incarcerated women.

[7][17] In these situations, children may be "missocialized" by caregivers who offer them drugs, force them to steal, or exploit them as prostitutes.

[7] Prostitution, property crimes, and drug distribution become means of survival for young female runaways.

[7][17][18] Seventy-five percent of the women studied by Browne, Miller, and Maguin[11] at the Bedford Hills Maximum Security Correctional Facility reported histories of partner abuse.

[17][21] There is evidence that incarcerated women were forced by their partners– through physical attacks or threats –to commit murders, robbery, check fraud,[7] and sell or carry drugs.

[17][21] Richie observed this gender entrapment among battered African-American women in New York City jails, whom she described as being "compelled to crime.

"[17] Financially abusive partners may manipulate women into debt until they are left with no resources, and as a result, are more likely to turn to criminal activities to support themselves.

[7] Abusive partners sometimes isolate a woman from her social networks, thus structurally dislocating her from all legitimate institutions, such as family.

[7][22] Women reported feeling a sense of rejection and worthlessness as a result of this isolation, and often coped by using drugs.

In contrast, some research strips women of their agency and portrays them as "passive victims of oppressive social structures, relations, and substances, or some combination thereof.

[24] Critics hold that it is essential for research on women in crime to consider both the social-historical context and the woman's individual motivations.

[24] Just as gender acts as an organizing principle in society, race and class also shape opportunity structures and social positions.

An intersectional, or interlocking, perspective takes into account that other social identities impact an individual's victimization and path into crime.

Multicultural feminism is necessary to fully understand how social identities interact with traumatic life course events to pave the way to prison.

Feminist scholars have strongly discouraged researchers from portraying female offenders and victims as mutually exclusive groups.

[24] Instead, critics argue the line between them should be blurred because women's involvement in crime is so often linked to their subordinate social positions, which make them vulnerable to victimization.