Fernando Vélaz de Medrano y Bracamonte

During this time, he corresponded with the Prince of Asturias, the future Charles IV of Spain, informing him of the rebellion and denouncing widespread corruption by royal officials, particularly in their administration of tobacco and playing card monopolies imposed by Minister José de Gálvez.

"[4] His father Jaime had formed a close relationship with Frederick, Prince of Wales, and King George II of Great Britain, obtaining a pension from both sovereigns during his stay in London, totaling 1,000 pounds.

[5] Returning to Spain in 1748, Fernando spent his early childhood in Ávila, where he was catechized on 2 November 1749 in the Chapel of Our Lady of the Annunciation by the parish priest of Saint Vincent Martyr.

[1] His uncle, the Marquess of Fuente el Sol, took charge of his education and secured his admission in 1757 to the prestigious Royal Seminary of Nobles in Madrid.

The rebellion, led by José Gabriel Condorcanqui, also known as Tupac Amaru II, sought to overthrow Spanish colonial rule in the Andean region.

It was one of the largest and most disruptive uprisings against the Spanish Crown in South America during the 18th century, and its ripple effects extended across the viceroyalties, including the Río de la Plata.

Though the uprising was centered in the Viceroyalty of Peru, its ramifications prompted viceroys across Spanish America to bolster defenses and address the unrest's potential to spread.

According to contemporary sources, he worked closely with Vértiz to coordinate communications and defensive strategies to prevent the rebellion from gaining traction in the southern viceroyalty.

According to Jacinto Ventura de Molina, Fernando maintained correspondence with the Prince of Asturias, the future King Charles IV of Spain, in which he reported on the rebellion’s progress and the policies that may have contributed to its escalation.

[6] In 1781, Fernando Vélaz de Medrano was arrested by order of Secretary of War Múzquiz for alleged intrigue in the quarters of the Prince of Asturias, the future King Charles IV.

[7] The specific accusation involved Fernando’s communications with the Prince, in which he reportedly criticized the policies of Gálvez, particularly the tobacco and playing card monopolies, as major contributors to the Tupac Amaru Rebellion.

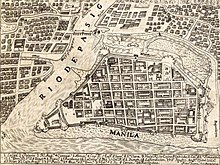

[6] Although Fernando’s confinement in Manila was initially intended to be as restrictive as the terms decreed in 1781, the passage of time and geographic distance led to a gradual relaxation of these conditions.

According to Jacinto Ventura de Molina, Fernando lived a relatively unconfined life: The marquess resided two leagues from Manila in the countryside house of a local landowner who took him in.

A royal order dated June 2, 1785, directed that 30,000 reales de vellón deposited in the Secretariat of the Indies be delivered to the Marquess of Tabuérniga, ensuring his financial stability.

[14][15][16] Though Fernando’s life in Manila offered relative comfort compared to the harsh terms of his original confinement, the many years of exile took a significant toll on his health.

Despite becoming the Marquess of Fuente el Sol, Cañete, and Navamorcuende, and attaining the rank of Grandee of Spain of the second class, his new status did little to improve his circumstances.

His family made repeated pleas to Prime Minister Floridablanca and King Charles III for his return, including a heartfelt appeal from the Marchioness of Fuente el Sol, but all requests were dismissed.

Initially, Fernando and his entourage sought passage on a ship from the Royal Philippine Company, but ongoing hostilities between Britain and Spain made this impossible.

Campoy described his master as “a second Job, slowly recovering as his physical condition declined daily.” Despite his failing health, Fernando and his companions managed to secure passage on an English packet ship called Swallow, believing it would stop in Lisbon, allowing them to complete their journey to Spain overland.

On November 22, 1791, just two months later, Fernando Vélaz de Medrano y Bracamonte y Dávila died near the Cape of Good Hope, never fulfilling his dream of returning to his homeland.

[6] He left behind two illegitimate children in the Philippines from an extramarital relationship with a Tagalog woman named Luisa Cuenca, a native of Bacoor, whose family belonged to the Filipino nobility known as the Principalía.

[6][18][19] Jose E. Romero's maternal grandmother Aleja Silva Calumpang was a great-granddaughter of Fernando Vélaz de Medrano y Bracamonte y Dávila.