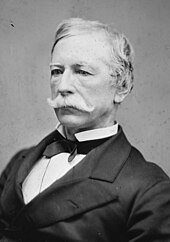

Fernando Wood

Fernando Wood (June 14, 1812 – February 13, 1881) was an American Democratic Party politician, merchant, and real estate investor who served as the 73rd and 75th Mayor of New York City.

After rapidly rising through Tammany Hall, Wood served a single term in the U.S. House before returning to private life and building a fortune in real estate speculation and maritime shipping.

Throughout his career, Wood expressed political sympathies for the Southern United States, including during the American Civil War.

[4] During Fernando's childhood, his father moved the family frequently: from Philadelphia to Shelbyville, Kentucky; New Orleans; Havana, Cuba; Charleston, South Carolina; and finally New York City, where he opened a tobacconist store in 1821.

[8] In 1835, Wood started a ship chandler firm with Francis Secor and Joseph Scoville, but the business failed during the Panic of 1837.

He joined the nascent Jacksonian Democratic Party, possibly influenced by his hatred of the Second Bank of the United States, which he blamed for his father's ruin.

However, following the Panic of 1837 and a Locofoco food riot, Wood worked to advance radical anti-bank politics within the Young Men's Committee.

Wood's move was politically prescient; in September 1837, President Martin Van Buren, a Tammany Hall ally, signaled approval of Locofocoism.

He engaged in a war of words with New York American editor Charles King, who revealed that Wood had been found liable for $2,143.90 in overdraft fees after he fraudulently withdrew from his bank on the basis of a bookkeeping error.

However, he supported federal funding in New York, including appropriations for harbor improvements, fortifications, and the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

[17] Wood also lobbied the U.S. State Department for protections for Irish political prisoners, some of whom were naturalized Americans, whom the British forcibly resettled on Tasmania.

Wise for a patronage appointment as the State Department's local despatch agent, despite previously having tried to abolish the role when he was a congressman.

Though Secretary of State Abel Upshur refused, he was soon killed in an accident aboard the USS Princeton and succeeded by John C. Calhoun, who granted Wood the appointment on May 8, 1844.

[19] With his government job as a subsidy and political power base, Wood expanded his business and rented a new home in upper Manhattan with three servants.

Calhoun supporters, seeking to peel Tammany away from Van Buren, invited Wood to strategy meetings and sought his advice on courting New York delegates.

[25] In October 1848, in the early stages of the California Gold Rush, Wood and four other partners chartered a barque, the John C. Cater, to sell goods and equipment in San Francisco.

The goods were sold at inflated prices, and the Cater maintained a profitable trade transporting passengers and lumber between Oregon and San Francisco.

In 1851, Wood was indicted by a grand jury, but the judges quashed the charges because the statute of limitations expired a day before the court was to rule on the matter.

[27] During the case, Wood maintained his innocence and brought a libel suit against the New York Sun for prematurely printing details of Marvine's deposition.

[30] Wood began organizing his political return in November 1853, courting both the Soft and Hard factions in opposition to Free Soil Democrats, who opposed any extension of slavery whatsoever.

In his first two-year term, Wood sought to strengthen the office of mayor and establish "one-man rule" in advance of proposals to unilaterally modernize the city's economy, improve its public works, and reduce wealth inequality.

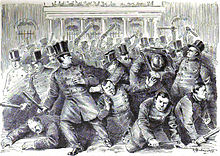

On election day, Wood furloughed or relieved many police officers of duty, allowing his own gang, the Dead Rabbits, to menace voters and steal ballot boxes.

Despite his evident abuse of police powers and encouragement of violence, a grand jury declined to indict Wood on the grounds that such practices were common in the city's history and at the time.

In April, the Republican legislature passed a new City Charter which truncated Wood's current term to one year,[38] a Police Reform Act dissolving Wood's Municipal police in favor of a Metropolitan state unit,[39] and an Excise Act implementing restrictive liquor licensing throughout the state.

The economic devastation of the Panic of 1857 dominated the campaign, and Wood pursued public works programs to provide jobs and food for the city's poor citizens.

In 1860, at a meeting to choose New York's delegates to the Democratic convention in Charleston, S.C., Wood outlined his case against the abolitionist cause and the "Black Republicans" who supported it.

Wood was one of the main opponents of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution which abolished slavery and was critical in blocking the measure in the House when it first came up for a vote in June 1864.

Notwithstanding his censure, Wood still managed to defeat Dr. Francis Thomas, the Republican candidate, by a narrow margin in the election of that year.

[4] Wood's biographer Jerome Mushkat describes him as a totally self-reliant man of "soaring ambition" and "an almost dictatorial obsession to control men and events.

[54] He was buried in Trinity Church Cemetery, in New York, N.Y.[55] In Steven Spielberg's Lincoln, Wood is portrayed by Lee Pace as a leading opponent of the president and of the Thirteenth Amendment.