Fertilisation

In antiquity, Aristotle conceived the formation of new individuals through fusion of male and female fluids, with form and function emerging gradually, in a mode called by him as epigenetic.

[4] In 1784, Spallanzani established the need of interaction between the female's ovum and male's sperm to form a zygote in frogs.

Various plant groups have differing methods by which the gametes produced by the male and female gametophytes come together and are fertilised.

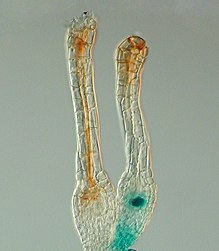

In bryophytes and pteridophytic land plants, fertilisation of the sperm and egg takes place within the archegonium.

[8] The pollen tube penetrates the stigma and elongates through the extracellular matrix of the style before reaching the ovary.

[9] The growth of the pollen tube has been believed to depend on chemical cues from the pistil, however these mechanisms were poorly understood until 1995.

Work done on tobacco plants revealed a family of glycoproteins called TTS proteins that enhanced growth of pollen tubes.

Transgenic plants lacking the ability to produce TTS proteins had slower pollen tube growth and reduced fertility.

[9] The rupture of the pollen tube to release sperm in Arabidopsis has been shown to depend on a signal from the female gametophyte.

ROS levels have been shown via GFP to be at their highest during floral stages when the ovule is the most receptive to pollen tubes, and lowest during times of development and following fertilisation.

[8] Pistil feeding assays in which plants were fed diphenyl iodonium chloride (DPI) suppressed ROS concentrations in Arabidopsis, which in turn prevented pollen tube rupture.

One primitive species of flowering plant, Nuphar polysepala, has endosperm that is diploid, resulting from the fusion of a sperm with one, rather than two, maternal nuclei.

It is believed that early in the development of angiosperm lineages, there was a duplication in this mode of reproduction, producing seven-celled/eight-nucleate female gametophytes, and triploid endosperms with a 2:1 maternal to paternal genome ratio.

For example, with watermelon, about a thousand grains of pollen must be delivered and spread evenly on the three lobes of the stigma to make a normal sized and shaped fruit.

[20] In long-established self-fertilising plants, the masking of deleterious mutations and the production of genetic variability is infrequent and thus unlikely to provide a sufficient benefit over many generations to maintain the meiotic apparatus.

Many females have the ability to store sperm for extended periods of time and can fertilise their eggs at their own desire.

[21] External fertilisation is advantageous in that it minimises contact (which decreases the risk of disease transmission), and greater genetic variation.

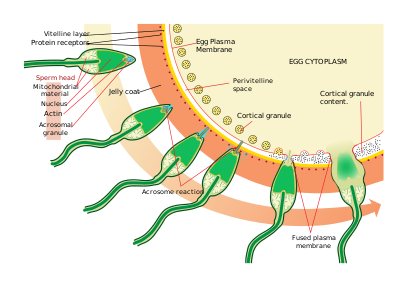

Resact is a 14 amino acid peptide purified from the jelly coat of A. punctulata that attracts the migration of sperm.

In another ligand/receptor interaction, an oligosaccharide component of the egg binds and activates a receptor on the sperm and causes the acrosomal reaction.

[29] The zona pellucida, a thick layer of extracellular matrix that surrounds the egg and is similar to the role of the vitelline membrane in sea urchins, binds the sperm.

[citation needed] This process ultimately leads to the formation of a diploid cell called a zygote.

[33] Its use makes it a subject of semantic arguments about the beginning of pregnancy, typically in the context of the abortion debate.

Insects in different groups, including the Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies) and the Hymenoptera (ants, bees, and wasps) practise delayed fertilisation.

In chytrid fungi, fertilisation occurs in a single step with the fusion of gametes, as in animals and plants.

There are three types of fertilisation processes in protozoa:[38] Algae, like some land plants, undergo alternation of generations.

[41] The sperm centriole, found near the male pronucleus, recruit egg Pericentriolar material proteins forming the zygote first centrosome.

Parthenogenesis occurs in many plants and animals and may be induced in others through a chemical or electrical stimulus to the egg cell.

Autogamy which is also known as self-fertilisation, occurs in such hermaphroditic organisms as plants and flatworms; therein, two gametes from one individual fuse.

Some relatively unusual forms of reproduction are:[45][46] Gynogenesis: A sperm stimulates the egg to develop without fertilisation or syngamy.

Charles Darwin, in his 1876 book The Effects of Cross and Self Fertilisation in the Vegetable Kingdom (pages 466-467) summed up his findings in the following way.