Field (physics)

In science, a field is a physical quantity, represented by a scalar, vector, or tensor, that has a value for each point in space and time.

A surface wind map,[4] assigning an arrow to each point on a map that describes the wind speed and direction at that point, is an example of a vector field, i.e. a 1-dimensional (rank-1) tensor field.

In the eighteenth century, a new quantity was devised to simplify the bookkeeping of all these gravitational forces.

[11] Maxwell, at first, did not adopt the modern concept of a field as a fundamental quantity that could independently exist.

Instead, he supposed that the electromagnetic field expressed the deformation of some underlying medium—the luminiferous aether—much like the tension in a rubber membrane.

Despite much effort, no experimental evidence of such an effect was ever found; the situation was resolved by the introduction of the special theory of relativity by Albert Einstein in 1905.

By doing away with the need for a background medium, this development opened the way for physicists to start thinking about fields as truly independent entities.

This was soon followed by the realization (following the work of Pascual Jordan, Eugene Wigner, Werner Heisenberg, and Wolfgang Pauli) that all particles, including electrons and protons, could be understood as the quanta of some quantum field, elevating fields to the status of the most fundamental objects in nature.

[11] That said, John Wheeler and Richard Feynman seriously considered Newton's pre-field concept of action at a distance (although they set it aside because of the ongoing utility of the field concept for research in general relativity and quantum electrodynamics).

Classical field theories remain useful wherever quantum properties do not arise, and can be active areas of research.

Elasticity of materials, fluid dynamics and Maxwell's equations are cases in point.

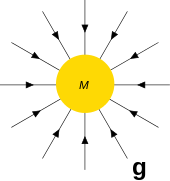

The gravitational field of M at a point r in space corresponds to the ratio between force F that M exerts on a small or negligible test mass m located at r and the test mass itself:[14] Stipulating that m is much smaller than M ensures that the presence of m has a negligible influence on the behavior of M. According to Newton's law of universal gravitation, F(r) is given by[14] where

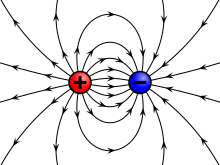

The force exerted by I on a nearby charge q with velocity v is where B(r) is the magnetic field, which is determined from I by the Biot–Savart law: The magnetic field is not conservative in general, and hence cannot usually be written in terms of a scalar potential.

Waves can be constructed as physical fields, due to their finite propagation speed and causal nature when a simplified physical model of an isolated closed system is set [clarification needed].

For electromagnetic waves, there are optical fields, and terms such as near- and far-field limits for diffraction.

Fluid dynamics has fields of pressure, density, and flow rate that are connected by conservation laws for energy and momentum.

if the density ρ, pressure p, deviatoric stress tensor τ of the fluid, as well as external body forces b, are all given.

Linear elasticity is defined in terms of constitutive equations between tensor fields, where

Assuming that the temperature T is an intensive quantity, i.e., a single-valued, continuous and differentiable function of three-dimensional space (a scalar field), i.e., that

[22] These three quantum field theories can all be derived as special cases of the so-called standard model of particle physics.

General relativity, the Einsteinian field theory of gravity, has yet to be successfully quantized.

As above with classical fields, it is possible to approach their quantum counterparts from a purely mathematical view using similar techniques as before.

A possible problem is that these RWEs can deal with complicated mathematical objects with exotic algebraic properties (e.g. spinors are not tensors, so may need calculus for spinor fields), but these in theory can still be subjected to analytical methods given appropriate mathematical generalization.

Usually this is done by writing a Lagrangian or a Hamiltonian of the field, and treating it as a classical or quantum mechanical system with an infinite number of degrees of freedom.

It is possible to construct simple fields without any prior knowledge of physics using only mathematics from multivariable calculus, potential theory and partial differential equations (PDEs).

More generally problems in continuum mechanics may involve for example, directional elasticity (from which comes the term tensor, derived from the Latin word for stretch), complex fluid flows or anisotropic diffusion, which are framed as matrix-tensor PDEs, and then require matrices or tensor fields, hence matrix or tensor calculus.

The scalars (and hence the vectors, matrices and tensors) can be real or complex as both are fields in the abstract-algebraic/ring-theoretic sense.

Physical symmetries are usually of two types: Fields are often classified by their behaviour under transformations of spacetime.

Much like statistical mechanics has some overlap between quantum and classical mechanics, statistical field theory has links to both quantum and classical field theories, especially the former with which it shares many methods.

We can define a continuous random field well enough as a linear map from a space of functions into the real numbers.