Electric charge

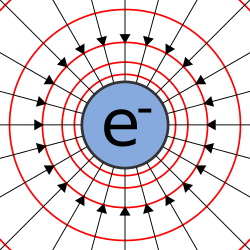

Electric charge (symbol q, sometimes Q) is a physical property of matter that causes it to experience a force when placed in an electromagnetic field.

Early knowledge of how charged substances interact is now called classical electrodynamics, and is still accurate for problems that do not require consideration of quantum effects.

Michael Faraday, in his electrolysis experiments, was the first to note the discrete nature of electric charge.

Robert Millikan's oil drop experiment demonstrated this fact directly, and measured the elementary charge.

An ion is an atom (or group of atoms) that has lost one or more electrons, giving it a net positive charge (cation), or that has gained one or more electrons, giving it a net negative charge (anion).

The coulomb is defined as the quantity of charge that passes through the cross section of an electrical conductor carrying one ampere for one second.

The Greeks observed that the charged amber buttons could attract light objects such as hair.

[15] In contrast to astronomy, mechanics, and optics, which had been studied quantitatively since antiquity, the start of ongoing qualitative and quantitative research into electrical phenomena can be marked with the publication of De Magnete by the English scientist William Gilbert in 1600.

[16] In this book, there was a small section where Gilbert returned to the amber effect (as he called it) in addressing many of the earlier theories,[15] and coined the Neo-Latin word electrica (from ἤλεκτρον (ēlektron), the Greek word for amber).

[20] Other European pioneers were Robert Boyle, who in 1675 published the first book in English that was devoted solely to electrical phenomena.

[21] His work was largely a repetition of Gilbert's studies, but he also identified several more "electrics",[22] and noted mutual attraction between two bodies.

[21] In 1729 Stephen Gray was experimenting with static electricity, which he generated using a glass tube.

Further experiments (e.g., extending the cork by putting thin sticks into it) showed—for the first time—that electrical effluvia (as Gray called it) could be transmitted (conducted) over a distance.

[23] Through these experiments, Gray discovered the importance of different materials, which facilitated or hindered the conduction of electrical effluvia.

[23] Gray also discovered electrical induction (i.e., where charge could be transmitted from one object to another without any direct physical contact).

[25] Gray's discoveries introduced an important shift in the historical development of knowledge about electric charge.

The fact that electrical effluvia could be transferred from one object to another, opened the theoretical possibility that this property was not inseparably connected to the bodies that were electrified by rubbing.

[26] In 1733 Charles François de Cisternay du Fay, inspired by Gray's work, made a series of experiments (reported in Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences), showing that more or less all substances could be 'electrified' by rubbing, except for metals and fluids[27] and proposed that electricity comes in two varieties that cancel each other, which he expressed in terms of a two-fluid theory.

[30] Up until about 1745, the main explanation for electrical attraction and repulsion was the idea that electrified bodies gave off an effluvium.

[31] Benjamin Franklin started electrical experiments in late 1746,[32] and by 1750 had developed a one-fluid theory of electricity, based on an experiment that showed that a rubbed glass received the same, but opposite, charge strength as the cloth used to rub the glass.

[37] One physicist suggests that Watson first proposed a one-fluid theory, which Franklin then elaborated further and more influentially.

In 1800 Alessandro Volta was the first to show that charge could be maintained in continuous motion through a closed path.

[42] In 1833, Michael Faraday sought to remove any doubt that electricity is identical, regardless of the source by which it is produced.

[45] In 1838, Faraday also put forth a theoretical explanation of electric force, while expressing neutrality about whether it originates from one, two, or no fluids.

In developing a field theory approach to electrodynamics (starting in the mid-1850s), James Clerk Maxwell stops considering electric charge as a special substance that accumulates in objects, and starts to understand electric charge as a consequence of the transformation of energy in the field.

[47] This pre-quantum understanding considered magnitude of electric charge to be a continuous quantity, even at the microscopic level.

The exactly opposite properties of the two kinds of electrification justify our indicating them by opposite signs, but the application of the positive sign to one rather than to the other kind must be considered as a matter of arbitrary convention—just as it is a matter of convention in mathematical diagram to reckon positive distances towards the right hand.

In many situations, it suffices to speak of the conventional current without regard to whether it is carried by positive charges moving in the direction of the conventional current or by negative charges moving in the opposite direction.

Beware that, in the common and important case of metallic wires, the direction of the conventional current is opposite to the drift velocity of the actual charge carriers; i.e., the electrons.

This law is inherent to all processes known to physics and can be derived in a local form from gauge invariance of the wave function.