Fifth Crusade

There, cardinal Pelagius Galvani arrived as papal legate and de facto leader of the Crusade, supported by John of Brienne and the masters of the Templars, Hospitallers and Teutonic Knights.

In the end, very few Frenchmen took part in the expedition of 1217, unwilling to go in the company of Germans and Hungarians, with France represented by Aubrey of Reims and the bishops of Limoges and Bayeux, Jean de Veyrac and Robert des Ablèges.

[11] In order to protect Raoul of Merencourt, the Latin patriarch of Jerusalem, on his return trip to the kingdom, Innocent III tasked John of Brienne to provide escort.

He arrived at his new position as Bishop of Acre in 1216 and shortly thereafter Honorius III tasked him with preaching the Crusade in the Latin settlements of Syria, made difficult with the rampant corruption at the port cities.

As in previous crusading seaborne journeys, the fleet was dispersed by storms and only gradually managed to reach the Portuguese city of Lisbon after making a stopover at the famous shrine of Santiago de Compostela.

[22] A group of Frisians who refused to aid the Portuguese with their siege plans against Alacácer do Sal, preferred to raid several coastal towns on their way to the Holy Land.

He was willing to make concessions to avoid war, and favoured the Italian maritime states of Venice and Pisa, both for trading reasons and to preclude them from supporting further crusades.

Only once, in 1207, did he directly confront the Crusaders, capturing al-Qualai'ah, besieging Krak des Chevaliers and advancing to Tripoli, before accepting an indemnity from Bohemond IV in exchange for peace.

[28] Az-Zahir maintained an alliance with both Antioch and Kaykaus I, the Seljuk sultan of Rûm, to check the influence of Leo I of Armenia, as well as to keep his options open to challenge his uncle.

[30] Andrew II had been called on by the pope in July 1216 to fulfill his father Béla III's vow to lead a crusade, and finally agreed, having postponed three times earlier.

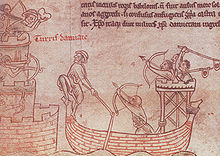

[52][53] Oliver of Paderborn, supported by his Frisian and German followers, demonstrating considerable ingenuity and leadership, constructed an ingenious siege engine combining the best features of the earlier models.

A group from England, smaller than expected arrived shortly, led by Ranulf de Blondeville, and Oliver and Richard, illegitimate sons of King John.

[57] A group of French Crusaders that arrived at the end of October included Guillaume II de Genève, archbishop of Bordeaux, and the newly elected bishop of Beauvais, Milo of Nanteuil.

Al-Kamil considered fleeing to the Ayyubid emirate of Yemen, ruled by his son al-Mas'ud Yusuf, but the arrival of his brother al-Mu'azzam with reinforcements from Syria ended the conspiracy.

In the Holy Land, al-Mu'azzam's forces began dismantling fortifications at Mount Tabor and other defensive positions, as well as Jerusalem itself, in order to deny their protection should the Crusaders prevail there.

This included his earlier provisions plus paying for the restoration of the damaged fortifications, the return of the portion of the True Cross lost at the battle of Hattin and the release of prisoners.

Pelagius' view that victory was possible was supported by the continued arrival of new Crusades, most notably an English force led by Savari de Mauléon, a seneschal of the late John of England.

[72] With the negotiations with the Crusaders stalled and Damietta isolated, on 3 November 1219 al-Kamil sent a resupply convoy through the sector manned by the troops of the Frenchman Hervé IV of Donzy.

In John's absence, Pelagius left the sea routes between Damietta and Acre unguarded, and a Muslim fleet attacked the Crusaders in the port of Limassol, resulting in over a thousand casualties.

The Ayyubids regarded the Mongol ouster of Ala ad-Din Muhammad II, shah of the Khwarazmians, as destroying one of their main enemies, allowing them to focus on the invaders at Damietta.

The relative calm in Egypt enabled al-Mu'azzam, returning to Syria after the defeat at Damietta, to attack the remaining coastal strongholds, taking Caesarea.

By October, he had further degraded the defenses of Jerusalem and unsuccessfully attacking Château Pèlerin, defended by Peire de Montagut and his Templars, recently released from their duty in Egypt.

In December 1220, Honorius III announced that Frederick II would soon be sending troops, expected now in March 1221, with the newly crowned emperor leaving for Egypt in August.

Then in July 1221, rumors began that the army of one King David,[88] a descendant of the legendary Prester John, was on its way from the east to the Holy Land to join the Crusade and gain release of the sultan's Christian captives.

Damietta was well-garrisoned and a naval squadron under fleet admiral Henry of Malta, and Sicilian chancellor Walter of Palearia and German imperial marshal Anselm of Justingen, had been sent by Frederick II.

They offered the sultan withdrawal from Damietta and an eight-year truce in exchange for allowing the Crusader army to pass, the release of all prisoners, and the return of the relic of the True Cross.

The Palästinalied is a famous lyric poem by Walther von der Vogelweide written in Middle High German describing a pilgrim travelling to the Holy Land during the height of the Fifth Crusade.

[100] The primary Western sources of the Fifth Crusade were first complied in Gesta Dei per Francos (God's Work through the Franks) (1611), by French scholar and diplomat Jacques Bongars.

[117] German historian Reinhold Röhricht also compiled two collections of works concerning the Fifth Crusade: Scriptores Minores Quinti Belli sacri (1879)[118] and its continuation Testimonia minora de quinto bello sacro (1882).

Tertiary sources include works by Louis Bréhier in the Catholic Encyclopedia,[128] Ernest Barker in the Encyclopædia Britannica,[129] and Philip Schaff in the Schaff-Herzog Encyclopaedia of Religious Knowledge.