Filamentation

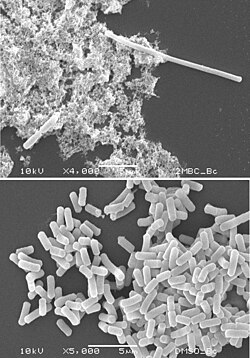

Filamentation is the anomalous growth of certain bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, in which cells continue to elongate but do not divide (no septa formation).

[6][7] The number and length of filaments within a bacterial population increases when the bacteria are exposed to different physical, chemical and biological agents (e.g. UV light, DNA synthesis-inhibiting antibiotics, bacteriophages).

Bacteria inhibit septation by synthesizing protein SulA, an FtsZ inhibitor that halts Z-ring formation, thereby stopping recruitment and activation of PBP3.

It has been observed in response to temperature shocks,[16] low water availability,[17] high osmolarity,[18] extreme pH,[19] and UV exposure.

[9] For example, if bacteria are deprived of the nucleobase thymine, this disrupts DNA synthesis and induces SOS-mediated filamentation.

[23] Certain bacterial species, such as Paraburkholderia elongata, will also filament as a result of a tendency to accumulate phosphate in the form of polyphosphate, which can chelate metal cofactors needed by division proteins.

Overcrowding of the periplasm or envelope can also induce filamentation in Gram-negative bacteria by disrupting normal divisome function.