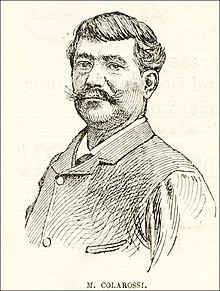

Filippo Colarossi

Writing in 1924, they maintained that Colarossi had recently returned to Picinisco, having sold some works by the artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903).

Born to poor parents, farm labourer (contadino) Fiori Colarossi (1779–1853)[6][7] and his wife Anna (née Ferri; 1811–?

),[6] Colarossi grew up in Picinisco, a small hilltop village south east of Rome, in the Province of Frosinone of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

As a Catholic and loyal royal marine, this was an unwelcome outcome to Colarossi's elder brother Angelo (1836–1916);[6][8] thus, in late 1860 or in 1861, they made their way, mostly by steam boat (Naples–Marseilles, then Avignon–Lyon), to Paris, France, to escape widespread poverty and obligatory military conscription.

Starting in 1853, Napoleon III (1808–1873) and his prefect of the Seine, Georges-Eugène Haussmann (1809–1891), had initiated an extensive series of public works projects to clean up, rebuild and modernise the capital.

Nonetheless, Colarossi chose to remain a model in Paris, which was fast becoming the Mecca of the Fine Arts, while Angelo left for London, England, in 1864, where he continued his newfound occupation, started a family and became an Urban District Councillor.

Filippo Colarossi became a very ambitious and successful model, not least at the École Impériale des Beaux-Arts (Imperial School of Fine Arts) on the Left Bank, where he drew an annual, retaining fee of 500 francs.

[18] He was also a favourite model of the classicist painter Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier (1815–1891), who he met when staying at Saint-Germain-en-Laye to escape the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871).

Colarossi wanted to establish his own school where he could provide an art education for the many students, male and female, that were flocking to Paris.

This academy was established by the model[23][24] and painter of miniatures[25] Martin François Suisse (1781–1859) at 4, Quai des Orfèvres on the Île de la Cité, Paris in 1817.

Then into an open square court fitted up with statues and plants and bounded by houses whose facades are ornamented with weather-stained busts and casts.

Colarossi was from the start a firm believer in mixed classes as it was an advantage to both men and women to be able to watch, compare and discuss each other's work.

For example, to study at the Colarossi Academy, Rue de la Grande Chaumière, the following fees applied in 1887:[42] The usual explanation for the difference was that the attendance of women could not be relied upon.

Women often remained for a month or two, but men tended to stay for years, many having the intention of seeking entry to the École des Beaux-Arts.

It must be remembered that only in 1897, after a long and heated campaign by activists, were women finally allowed to sit the entrance exam to the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris and perhaps be one of the few to study there for free, albeit with some restrictions.

Penelope Little states that Colarossi actively enticed his impoverished countrymen to Paris where they could provide a constant and plentiful supply of affordable models.

Colarossi's compatriots became very popular models for thirty or so years before their fortunes slowly began to wane due to the move from classicism to realism in art.

[46] Men, women and children sporting a variety of attire from mundane city rags to traditional costumes waited and hoped to find employment for the week knowing that they could receive more pay than in other schools.

In the 1880s and 90s for example, they included painters Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848–1884), Gustave-Claude-Etienne Courtois (1852–1923), Raphaël Collin (1850–1916), Louis-Auguste Girardot (1856–1933), René Schützenberger (1860–1916), Jean-André Rixens (1846–1925) and Édouard Debat-Ponsan (1847–1913).

On Earth, he was proud of the fact that he had the pick of the best Italian models and talented teachers who took great pride in doing their utmost for the school.

Writing in 1889, French's view is more down-to-earth: "The heads of the private schools, …, are not distinguished artists at all, but rather business men, managers of tact and address.

"[51] Writing in 1896, when she was a student at the academy, Alice Muskett gave another realistic, more detailed and nuanced, description of the man and the personal attributes that contributed to his success: " 'Il Padrone', M. Colarossi, comes in to see how many nouvelles there are, and also that everything goes well.

... As far as one can judge, Colarossi rules his little world wisely and fairly, and he seems to possess the royal gift of remembering everyone's face and recognising them when he meets them.

The association was one of the most prestigious bastions of the Beaux-Arts and membership was a way of obtaining affirmation of one's artistic credentials and finding new contacts to further one's ambitions.

In 1893, he and some of his students organised a 40 km, summer, bicycle race for painters, sculptors and architects under the patronage of the newspapers Le Vélo and La Bicyclette.

Colarossi was the organising committee's treasurer, while artists Carolus Duran (1837–1917), Courtois and Alfred Philippe Roll (1846–1919) were honorary presidents.

He also took part, along with others, in a twelve hour, endurance match against the noted journalist and cycle racer Édouard de Perrodil (1860–1931).

[74] The robust, hard-working model and renowned, art-school proprietor, began to stroll the boulevards, to frequent chic cafés and develop a penchant for English clothing.

The possibility of its imminent demolition so worried one of its American students, that (s)he wrote a reader's letter to the New York Herald asking for a rich compatriot to come forward who would be prepared to build a new, flagship, art school on the academy's hallowed ground.

[78] Seemingly, Colarossi's son Ernest found the necessary capital, as he is recorded as succeeding his father in Le Courrier,[79] a daily journal of judicial and legal notices, also on 18 April.