Paul Gauguin

His paintings from that period, characterized by vivid colors and Symbolist themes, would prove highly successful among the European viewers for their exploration of the relationships between people, nature, and the spiritual world.

Gauguin initially found it difficult to re-enter the art world in Paris and spent his first winter back in real poverty, obliged to take a series of menial jobs.

The most important of these is Four Breton Women, which shows a marked departure from his earlier Impressionist style as well as incorporating something of the naive quality of Caldecott's illustration, exaggerating features to the point of caricature.

[52] In Gauguin's The Yellow Christ (1889), often cited as a quintessential Cloisonnist work, the image was reduced to areas of pure colour separated by heavy black outlines.

After discovering that land on Taboga was priced far beyond reach (and after falling deathly ill on the island where he was subsequently interned in a yellow fever and malaria sanatorium),[54] he decided to leave Panama.

[77] After visiting his wife and children in Copenhagen, for what turned out to be the last time, Gauguin set sail for Tahiti on 1 April 1891, promising to return a rich man and make a fresh start.

[96][97][98][99] Teha'amana was the subject of several of Gauguin's paintings, including Merahi metua no Tehamana and the celebrated Spirit of the Dead Watching, as well as a notable woodcarving Tehura now in the Musée d'Orsay.

His return is characterised by Thomson as an essentially negative one, his disillusionment with the Paris art scene compounded by two attacks on him in the same issue of Mercure de France;[116][117] one by Emile Bernard, the other by Camille Mauclair.

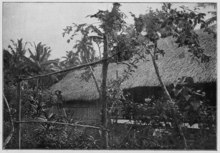

He built a spacious reed and thatch house at Puna'auia in an affluent area ten miles east of Papeete, settled by wealthy families, in which he installed a large studio, sparing no expense.

Thomson cites Oyez Hui Iesu (Christ on the Cross), a wooden cylinder half a metre (20") tall featuring a curious hybrid of religious motifs.

[131] Mathews notes a return to Christian symbolism that would have endeared him to the colonists of the time, now anxious to preserve what was left of native culture by stressing the universality of religious principles.

The androgynous nature of the image has attracted critical attention, giving rise to speculation that Gauguin intended to depict a māhū (i.e. a third gender person) rather than a taua or priest.

At present you are a unique and legendary artist, sending to us from the remote South Seas disconcerting and inimitable works which are the definitive creations of a great man who, in a way, has already gone from this world.

As it happened, the relatively supportive Charpillet was replaced that December by another gendarme, Jean-Paul Claverie, from Tahiti, much less well disposed to Gauguin and who in fact had fined him in his earliest Mataiea days for public indecency, having caught him bathing naked in a local stream following complaints from the missionaries there.

He included in it attacks on subjects as diverse as the local gendarmerie, Bishop Martin, his wife Mette and the Danes in general, and concluded with a description of his personal philosophy conceiving life as an existential struggle to reconcile opposing binaries.

[213] At the beginning of 1903, Gauguin engaged in a campaign designed to expose the incompetence of the island's gendarmes, in particular Jean-Paul Claverie, for taking the side of the natives directly in a case involving the alleged drunkenness of a group of them.

Artists and movements in the early 20th century inspired by him include Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, André Derain, Fauvism, Cubism, and Orphism, among others.

[235] Gauguin's posthumous retrospective exhibitions at the Salon d'Automne in Paris in 1903, and an even larger one in 1906, had a stunning and powerful influence on the French avant-garde and in particular Pablo Picasso's paintings.

In the autumn of 1906, Picasso made paintings of oversized nude women and monumental sculptural figures that recalled the work of Paul Gauguin and showed his interest in primitive art.

An artist could also confound conventional notions of beauty, he demonstrated, by harnessing his demons to the dark gods (not necessarily Tahitian ones) and tapping a new source of divine energy.

If in later years Picasso played down his debt to Gauguin, there is no doubt that between 1905 and 1907 he felt a very close kinship with this other Paul, who prided himself on Spanish genes inherited from his Peruvian grandmother.

He sought out a bare emotional purity of his subjects conveyed in a straightforward way, emphasizing major forms and upright lines to clearly define shape and contour.

[252] This complemented one of Gauguin's favorite themes, which was the intrusion of the supernatural into day-to-day life, in one instance going so far as to recall ancient Egyptian tomb reliefs with Her Name is Vairaumati and Ta Matete.

[254] He states: In an 1888 letter to Schuffenecker, Gauguin explains the enormous step he had taken away from Impressionism and that he was now intent on capturing the soul of nature, the ancient truths and character of its scenery and inhabitants.

Gauguin was not hindered by his printing inexperience, and made a number of provocative and unorthodox choices, such as a zinc plate instead of limestone (lithography), wide margins and large sheets of yellow poster paper.

Despite often being a source of practice for related paintings, sculptures or woodcuts, his monotype innovation offers a distinctly ethereal aesthetic; ghostly afterimages that may express his desire to convey the immemorial truths of nature.

Gauguin's series is starkly unified with black and white aesthetic and may have intended the prints to be similar to a set of myriorama cards, in which they may be laid out in any order to create multiple panoramic landscapes.

[261] He printed the work on tissue-thin Japanese paper and the multiple proofs of gray and black could be arranged on top of one another, each transparency of colour showing through to produce a rich, chiaroscuro effect.

With these transfers he created depth and texture by printing multiple layers onto the same sheet, beginning with graphite pencil and black ink for delineation, before moving to blue crayon to reinforce line and add shading.

[272] His depictions of Polynesian women have been described as "racial fantasy forged from a position of patriarchal, colonialist power" with some critics pointing to Gauguin's sexual relationships with teenage Tahitian girls.