Film noir

[26] M (1931), shot only a few years before director Fritz Lang's departure from Germany, is among the first crime films of the sound era to join a characteristically noirish visual style with a noir-type plot, in which the protagonist is a criminal (as are his most successful pursuers).

Directors such as Lang, Jacques Tourneur, Robert Siodmak and Michael Curtiz brought a dramatically shadowed lighting style and a psychologically expressive approach to visual composition (mise-en-scène) with them to Hollywood, where they made some of the most famous classic noirs.

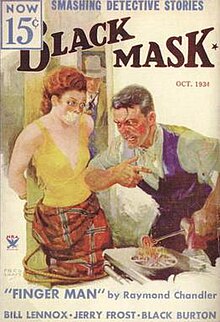

Not only were Chandler's novels turned into major noirs—Murder, My Sweet (1944; adapted from Farewell, My Lovely), The Big Sleep (1946), and Lady in the Lake (1947)—he was an important screenwriter in the genre as well, producing the scripts for Double Indemnity, The Blue Dahlia (1946), and Strangers on a Train (1951).

From January through December deep shadows, clutching hands, exploding revolvers, sadistic villains and heroines tormented with deeply rooted diseases of the mind flashed across the screen in a panting display of psychoneurosis, unsublimated sex and murder most foul.

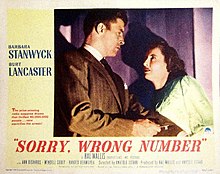

The signal film in this vein was Double Indemnity, directed by Billy Wilder; setting the mold was Barbara Stanwyck's femme fatale, Phyllis Dietrichson—an apparent nod to Marlene Dietrich, who had built her extraordinary career playing such characters for Sternberg.

The iconic noir counterpart to the femme fatale, the private eye, came to the fore in films such as The Maltese Falcon (1941), with Humphrey Bogart as Sam Spade, and Murder, My Sweet (1944), with Dick Powell as Philip Marlowe.

[62] Before leaving the United States while subject to the Hollywood blacklist, Jules Dassin made two classic noirs that also straddled the major/independent line: Brute Force (1947) and the influential documentary-style The Naked City (1948) were developed by producer Mark Hellinger, who had an "inside/outside" contract with Universal similar to Wanger's.

Jacques Tourneur had made over thirty Hollywood Bs (a few now highly regarded, most forgotten) before directing the A-level Out of the Past, described by scholar Robert Ottoson as "the ne plus ultra of forties film noir".

[68] He Walked by Night (1948), shot by Alton though credited solely to Alfred Werker, directed in large part by Mann, demonstrates their technical mastery and exemplifies the late 1940s trend of "police procedural" crime dramas.

[80] In addition to The Killers, Burt Lancaster's debut and a Hellinger/Universal co-production, Siodmak's other important contributions to the genre include 1944's Phantom Lady (a top-of-the-line B and Woolrich adaptation), the ironically titled Christmas Holiday (1944), and Cry of the City (1948).

In addition to the relatively looser constraints on character and message at lower budgets, the nature of B production lent itself to the noir style for economic reasons: dim lighting saved on electricity and helped cloak cheap sets (mist and smoke also served the cause).

In Criss Cross, Siodmak achieved these effects, wrapping them around Yvonne De Carlo, who played the most understandable of femme fatales; Dan Duryea, in one of his many charismatic villain roles; and Lancaster as an ordinary laborer turned armed robber, doomed by a romantic obsession.

Based on the novel by Raymond Chandler, it features one of Bogart's most famous characters, but in iconoclastic fashion: Philip Marlowe, the prototypical hardboiled detective, is replayed as a hapless misfit, almost laughably out of touch with contemporary mores and morality.

[107] Where Altman's subversion of the film noir mythos was so irreverent as to outrage some contemporary critics,[108] around the same time Woody Allen was paying affectionate, at points idolatrous homage to the classic mode with Play It Again, Sam (1972).

[112] Detective series, prevalent on American television during the period, updated the hardboiled tradition in different ways, but the show conjuring the most noir tone was a horror crossover touched with shaggy, Long Goodbye-style humor: Kolchak: The Night Stalker (1974–75), featuring a Chicago newspaper reporter investigating strange, usually supernatural occurrences.

[118] Director David Fincher followed the immensely successful neo-noir Seven (1995) with a film that developed into a cult favorite after its original, disappointing release: Fight Club (1999), a sui generis mix of noir aesthetic, perverse comedy, speculative content, and satiric intent.

[123] The characteristic work of David Lynch combines film noir tropes with scenarios driven by disturbed characters such as the sociopathic criminal played by Dennis Hopper in Blue Velvet (1986) and the delusionary protagonist of Lost Highway (1997).

The British miniseries The Singing Detective (1986), written by Dennis Potter, tells the story of a mystery writer named Philip Marlow; widely considered one of the finest neo-noirs in any medium, some critics rank it among the greatest television productions of all time.

Mann's output exemplifies a primary strain of neo-noir, or as it is affectionately called, "neon noir",[129][130] in which classic themes and tropes are revisited in a contemporary setting with an up-to-date visual style and rock- or hip hop-based musical soundtrack.

[141] Screenwriter David Ayer updated the classic noir bad-cop tale, typified by Shield for Murder (1954) and Rogue Cop (1954), with his scripts for Training Day (2001) and, adapting a story by James Ellroy, Dark Blue (2002); he later wrote and directed the even darker Harsh Times (2006).

[148] Writer-director Rian Johnson's Brick (2005), featuring present-day high schoolers speaking a version of 1930s hardboiled argot, won the Special Jury Prize for Originality of Vision at the Sundance Film Festival.

[149][150] Neo-noir films released in the 2010s include Kim Jee-woon’s I Saw the Devil (2010), Fred Cavaye’s Point Blank (2010), Na Hong-jin’s The Yellow Sea (2010), Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive (2011),[151] Claire Denis' Bastards (2013)[152][153] and Dan Gilroy's Nightcrawler (2014).

The animated sequences combine the characteristics of film noir with those of a pulp fiction graphic novel set in the mid-20th century, and they link conventional live-action documentary segments in which experts describe the potentially deadly phenomena.

[183] Adapted by director Robinson Devor from a novel by Charles Willeford, The Woman Chaser (1999) sends up not just the noir mode but the entire Hollywood filmmaking process, with each shot seemingly staged as the visual equivalent of an acerbic Marlowe wisecrack.

[200] In an analysis of the visual approach of Kiss Me Deadly, a late and self-consciously stylized example of classic noir, critic Alain Silver describes how cinematographic choices emphasize the story's themes and mood.

Bold experiments in cinematic storytelling were sometimes attempted during the classic era: Lady in the Lake, for example, is shot entirely from the point of view of protagonist Philip Marlowe; the face of star (and director) Robert Montgomery is seen only in mirrors.

There is usually an element of drug or alcohol use, particularly as part of the detective's method to solving the crime, as an example the character of Mike Hammer in the 1955 film Kiss Me Deadly who walks into a bar saying "Give me a double bourbon, and leave the bottle".

[215] A substantial trend within latter-day noir—dubbed "film soleil" by critic D. K. Holm—heads in precisely the opposite direction, with tales of deception, seduction, and corruption exploiting bright, sun-baked settings, stereotypically the desert or open water, to searing effect.

[227] Many of the prime composers, like the directors and cameramen, were European émigrés, e.g., Max Steiner (The Big Sleep, Mildred Pierce), Miklós Rózsa (Double Indemnity, The Killers, Criss Cross), and Franz Waxman (Fury, Sunset Boulevard, Night and the City).

[228] There is a widespread popular impression that "sleazy" jazz saxophone and pizzicato bass constitute the sound of noir, but those characteristics arose much later, as in the late-1950s music of Henry Mancini for Touch of Evil and television's Peter Gunn.

"A lot depends on who's in the saddle."

Bogart and Bacall in The Big Sleep .