Finding of Moses

He could also, at times, be regarded as a precursor or allegorical representation of things as diverse as the pope, Venice, the Dutch Republic, or Louis XIV.

Chapter 1:15–22 of the Book of Exodus recounts how during the captivity in Egypt of the Jewish people, the Pharaoh ordered: "Every Hebrew boy that is born you must throw into the Nile, but let every girl live."

The basket, usually with a rounded shape, is more common in Latin Christianity, and the ark more so in Jewish and Byzantine art; it is also used in Islamic miniatures.

Rivka Ulmer identifies recurrent "issues" in the iconography of the subject:[7] Medieval depictions are sometimes found in illuminated manuscripts and other media.

This probably accounts for it being represented as a faded fresco on the rear wall in the " Annunciation" by Jan van Eyck in the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

[8] It might also be regarded as prefiguring "the reception of Christ by the community of the faithful," [9] the Resurrection of Jesus, and the escape from the Massacre of the Innocents by the Flight into Egypt.

[13] The fourth century Brescia Casket includes it among its 4 or 5 relief scenes from the Life of Moses, and there is thought to have been a depiction (now lost) in the mosaics of Santa Maria Maggiore.

[17] The artist of a French Romanesque capital has enjoyed himself showing the infant Moses threatened by crocodiles and perhaps hippos, as often shown in classical depictions of the Nile landscape.

This sporadic treatment anticipates modern Biblical criticism: "The cameo of the birth of Moses does not fit the reality of the Nile, where crocodiles would make it dangerous to send a babe in a basket onto the water or even to bathe by the shore: even if the poor were forced to take the risk, no princess would.

[19] Independent pictures of the subject became increasingly popular in the Renaissance and Baroque periods, when the combination of several elegantly dressed and graceful ladies with a waterside landscape or classical architectural background made it attractive to artists and patrons.

[26] It has been suggested that the birth in 1638 of the future Louis XIV, whose parents had been childless for 23 years, may have been a factor in the interest of French artists.

[27] As well as the Catholic countries, there were also several versions in Dutch Golden Age painting, where the Old Testament subject was considered unobjectionable, orphanages were run by boards of "regents" drawn from the local wealthy, and the story of Moses was also given contemporary political significance.

[28] A painting of the subject shown on the wall behind "The Astronomer" by Vermeer may represent knowledge and science, as Moses was "learned in all the wisdom of the Egyptians.

[31] This is essentially a large aristocratic picnic, complete with musicians, dwarves, many dogs and a monkey, and strolling lovers, where the baby represents an object of polite curiosity.

Veronese had been called before the Inquisition in 1573 for the improper depiction of the Last Supper as an extravagant festivity mainly in modern dress, which he renamed "The Feast in the House of Levi."

[39] His figures wore the 17th-century idea of ancient dress, and the cityscapes in the distant background include pyramids and obelisks, where previously most artists, for example, Veronese, had not attempted to represent a specifically Egyptian setting.

For good measure the main three versions by Poussin all include a Roman-style Nilus, the god or personification of the Nile, reclining with a cornucopia, in two of them in company with a sphinx,[41] which follows a specific classical statue in the Vatican.

[42] His 1647 version for the banker Pointel (now Louvre) includes a hippopotamus hunt on the river in the background, adapted from the Roman Nile mosaic of Palestrina.

After that, attempts at an authentic Egyptian setting were irregular until the start of the 19th century, with the advent of modern Egyptology, and in art, the development of Orientalism.

By the late 19th century, exotic decor was often dominant, and several depictions concentrated on the ladies of the court, naked but for carefully researched jewellery.

[46] The earliest visual depiction of the "Finding" is a fresco in the Dura-Europos synagogue, datable to around 244, a unique large-scale survival of what may have been a large body of figurative Jewish religious art in the Hellenized Roman imperial period.

[49] There are a few illustrations in mainly medieval Jewish illuminated manuscripts, mostly of the Haggadah, some of which seem to share an iconographical tradition going back to late antiquity.

One Jewish tradition was that Pharaoh's daughter was identified as Bithiah, a leper who was bathing in the river to cleanse herself, seen as a ritual purification for which she would be naked.

Thus in Poussin's 1638 "Finding" in the Louvre a burly male emerges from the water with the child and basket, a detail sometimes copied by other painters.

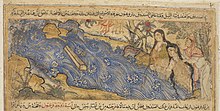

[62] There is an unusual depiction in the Edinburgh University Library manuscript of the Jami' al-tawarikh, an ambitious world history written in the Ilkhanate, now Iran, at the start of the 14th century.