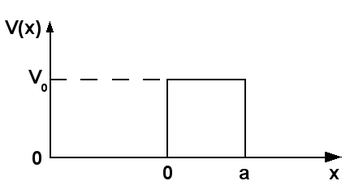

Rectangular potential barrier

In quantum mechanics, the rectangular (or, at times, square) potential barrier is a standard one-dimensional problem that demonstrates the phenomena of wave-mechanical tunneling (also called "quantum tunneling") and wave-mechanical reflection.

The problem consists of solving the one-dimensional time-independent Schrödinger equation for a particle encountering a rectangular potential energy barrier.

It is usually assumed, as here, that a free particle impinges on the barrier from the left.

Although classically a particle behaving as a point mass would be reflected if its energy is less than

In classical wave-physics, this effect is known as evanescent wave coupling.

The time-independent Schrödinger equation for the wave function

In any of these parts, the potential is constant, meaning that the particle is quasi-free, and the solution of the Schrödinger equation can be written as a superposition of left and right moving waves (see free particle).

becomes imaginary and the wave function is exponentially decaying within the barrier.

Inserting the wave functions, the boundary conditions give the following restrictions on the coefficients

At this point, it is instructive to compare the situation to the classical case.

To study the quantum case, consider the following situation: a particle incident on the barrier from the left side (

To find the amplitudes for reflection and transmission for incidence from the left, we put in the above equations

Due to the mirror symmetry of the model, the amplitudes for incidence from the right are the same as those from the left.

This effect, which differs from the classical case, is called quantum tunneling.

The transmission is exponentially suppressed with the barrier width, which can be understood from the functional form of the wave function: Outside of the barrier it oscillates with wave vector

If the barrier is much wider than this decay length, the left and right part are virtually independent and tunneling as a consequence is suppressed.

Equally surprising is that for energies larger than the barrier height,

Note that the probabilities and amplitudes as written are for any energy (above/below) the barrier height.

This expression can be obtained by calculating the transmission coefficient from the constants stated above as for the other cases or by taking the limit of

in the evaluated value for the limit, the above expression for T is successfully reproduced.

However it has proved to be a suitable model for a variety of real-life systems.

In the bulk of the materials, the motion of the electrons is quasi-free and can be described by the kinetic term in the above Hamiltonian with an effective mass

Often the surfaces of such materials are covered with oxide layers or are not ideal for other reasons.

This thin, non-conducting layer may then be modeled by a barrier potential as above.

Electrons may then tunnel from one material to the other giving rise to a current.

In that case, the barrier is due to the gap between the tip of the STM and the underlying object.

Since the tunnel current depends exponentially on the barrier width, this device is extremely sensitive to height variations on the examined sample.

On the other hand, many systems only change along one coordinate direction and are translationally invariant along the others; they are separable.

The Schrödinger equation may then be reduced to the case considered here by an ansatz for the wave function of the type:

All results from this article immediately apply to the delta potential barrier by taking the limits