Finite subdivision rule

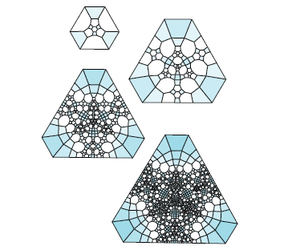

Subdivision rules in a sense are generalizations of regular geometric fractals.

Instead of repeating exactly the same design over and over, they have slight variations in each stage, allowing a richer structure while maintaining the elegant style of fractals.

[1] Subdivision rules have been used in architecture, biology, and computer science, as well as in the study of hyperbolic manifolds.

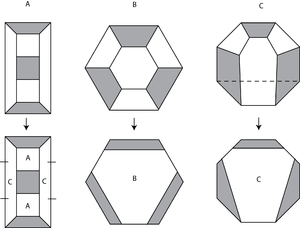

The tiling can be regular, but doesn't have to be: Here we start with a complex made of four quadrilaterals and subdivide it twice.

Barycentric subdivision is an example of a subdivision rule with one edge type (that gets subdivided into two edges) and one tile type (a triangle that gets subdivided into 6 smaller triangles).

[4] The subdivision rules show what the night sky would look like to someone living in a knot complement; because the universe wraps around itself (i.e. is not simply connected), an observer would see the visible universe repeat itself in an infinite pattern.

This is a subdivision rule for the trefoil knot, which is not a hyperbolic knot: And this is the subdivision rule for the Borromean rings, which is hyperbolic: In each case, the subdivision rule would act on some tiling of a sphere (i.e. the night sky), but it is easier to just draw a small part of the night sky, corresponding to a single tile being repeatedly subdivided.

This is what happens for the trefoil knot: And for the Borromean rings: Subdivision rules can easily be generalized to other dimensions.

Also, binary subdivision can be generalized to other dimensions (where hypercubes get divided by every midplane), as in the proof of the Heine–Borel theorem.

, called the subdivision complex, with a fixed cell structure such that

is the doubling map on the torus, wrapping the meridian around itself twice and the longitude around itself twice.

Subdivision rules can be used to study the quasi-isometry properties of certain spaces.

The quasi-isometry properties of the history graph can be studied using subdivision rules.

For instance, the history graph is quasi-isometric to hyperbolic space exactly when the subdivision rule is conformal, as described in the combinatorial Riemann mapping theorem.

[8] In 2007, Peter J. Lu of Harvard University and Professor Paul J. Steinhardt of Princeton University published a paper in the journal Science suggesting that girih tilings possessed properties consistent with self-similar fractal quasicrystalline tilings such as Penrose tilings (presentation 1974, predecessor works starting in about 1964) predating them by five centuries.

These subdivision surfaces (such as the Catmull-Clark subdivision surface) take a polygon mesh (the kind used in 3D animated movies) and refines it to a mesh with more polygons by adding and shifting points according to different recursive formulas.

Subdivision rules were applied by Cannon, Floyd and Parry (2000) to the study of large-scale growth patterns of biological organisms.

[6] Cannon, Floyd and Parry produced a mathematical growth model which demonstrated that some systems determined by simple finite subdivision rules can results in objects (in their example, a tree trunk) whose large-scale form oscillates wildly over time, even though the local subdivision laws remain the same.

[6] Cannon, Floyd and Parry also applied their model to the analysis of the growth patterns of rat tissue.

[6] They suggested that the "negatively curved" (or non-euclidean) nature of microscopic growth patterns of biological organisms is one of the key reasons why large-scale organisms do not look like crystals or polyhedral shapes but in fact in many cases resemble self-similar fractals.

[6] Cannon, Floyd, and Parry first studied finite subdivision rules as an attempt to prove the following conjecture: Cannon's conjecture: Every Gromov hyperbolic group with a 2-sphere at infinity acts geometrically on hyperbolic 3-space.

This conjecture was partially solved by Grigori Perelman in his proof[10][11][12] of the geometrization conjecture, which states (in part) that any Gromov hyperbolic group that is a 3-manifold group must act geometrically on hyperbolic 3-space.

Cannon and Swenson showed [13] that a hyperbolic group with a 2-sphere at infinity has an associated subdivision rule.

In the limit, the distances that come from these tilings may converge in some sense to an analytic structure on the surface.

The Combinatorial Riemann Mapping Theorem gives necessary and sufficient conditions for this to occur.

assigns a non-negative number called a weight to each tile of

can be given a length, defined to be the sum of the weights of all tiles in the path.

is the infimum of the length of all possible paths circling the ring (i.e. not nullhomotopic in R).

[7] The Combinatorial Riemann Mapping Theorem implies that a group

Thus, Cannon's conjecture would be true if all such subdivision rules were conformal.