Neolithic Revolution

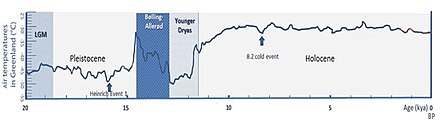

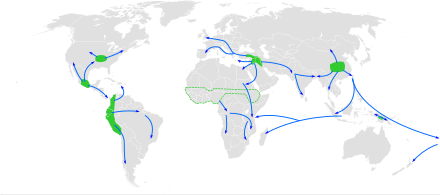

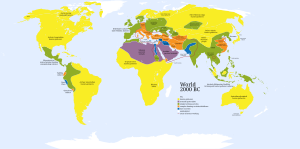

[2][3] Archaeological data indicate that the domestication of various types of plants and animals happened in separate locations worldwide, starting in the geological epoch of the Holocene 11,700 years ago, after the end of the last Ice Age.

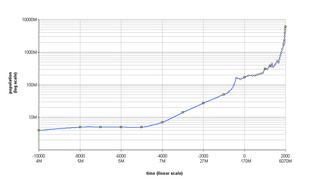

The Neolithic Revolution greatly narrowed the diversity of foods available, resulting in a decrease in the quality of human nutrition compared with that obtained previously from foraging,[5][6][7] but because food production became more efficient, it released humans to invest their efforts in other activities and was thus "ultimately necessary to the rise of modern civilization by creating the foundation for the later process of industrialization and sustained economic growth".

During the next millennia, it transformed the small and mobile groups of hunter-gatherers that had hitherto dominated human prehistory into sedentary (non-nomadic) societies based in built-up villages and towns.

These societies radically modified their natural environment by means of specialized food-crop cultivation, with activities such as irrigation and deforestation which allowed the production of surplus food.

In many regions, the adoption of agriculture by prehistoric societies caused episodes of rapid population growth, a phenomenon known as the Neolithic demographic transition.

Other factors that likely affected the health of early agriculturalists and their domesticated livestock would have been increased numbers of parasites and disease-bearing pests associated with human waste and contaminated food and water supplies.

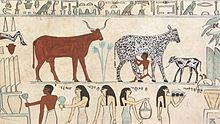

[26] Once agriculture started gaining momentum, around 9000 BP, human activity resulted in the selective breeding of cereal grasses (beginning with emmer, einkorn and barley), and not simply of those that favoured greater caloric returns through larger seeds.

[27][28] Gordon Hillman and Stuart Davies carried out experiments with varieties of wild wheat to show that the process of domestication would have occurred over a relatively short period of between 20 and 200 years.

[30] The process of domestication allowed the founder crops to adapt and eventually become larger, more easily harvested, more dependable[clarification needed] in storage and more useful to the human population.

Once early farmers perfected their agricultural techniques like irrigation (traced as far back as the 6th millennium BCE in Khuzistan[32][33]), their crops yielded surpluses that needed storage.

[39] Similarly, the African Zebu of central Africa and the domesticated bovines of the fertile-crescent – separated by the dry sahara desert – were not introduced into each other's region.

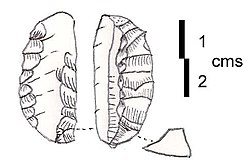

Use-wear analysis of five glossed flint blades found at Ohalo II, a 23,000-years-old fisher-hunter-gatherers' camp on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, Northern Israel, provides the earliest evidence for the use of composite cereal harvesting tools.

[49] The Heavy Neolithic Qaraoun culture has been identified at around fifty sites in Lebanon around the source springs of the River Jordan, but never reliably dated.

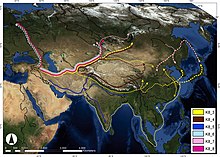

[50][37] In his book Guns, Germs, and Steel, Jared Diamond argues that the vast continuous east–west stretch of temperate climatic zones of Eurasia and North Africa gave peoples living there a highly advantageous geographical location that afforded them a head start in the Neolithic Revolution.

[52][53] The agricultural centre in northern China is believed to be the homelands of the early Sino-Tibetan-speakers, associated with the Houli, Peiligang, Cishan, and Xinglongwa cultures, clustered around the Yellow River basin.

They also came into contact with the early agricultural centres of Papuan-speaking populations of New Guinea as well as the Dravidian-speaking regions of South India and Sri Lanka by around 3,500 BP.

[53][60][61][62] During the 1st millennium CE, they also colonized Madagascar and the Comoros, bringing Southeast Asian food plants, including rice, to East Africa.

[68] Evidence of drainage ditches at Kuk Swamp on the borders of the Western and Southern Highlands of Papua New Guinea indicates cultivation of taro and a variety of other crops, dating back to 11,000 BP.

All Neolithic sites in Europe contain ceramics, and contain the plants and animals domesticated in Southwest Asia: einkorn, emmer, barley, lentils, pigs, goats, sheep, and cattle.

In general, colonization shows a "saltatory" pattern, as the Neolithic advanced from one patch of fertile alluvial soil to another, bypassing mountainous areas.

[79] Pottery prepared by sequential slab construction, circular fire pits filled with burnt pebbles, and large granaries are common to both Mehrgarh and many Mesopotamian sites.

[79] The postures of the skeletal remains in graves at Mehrgarh bear strong resemblance to those at Ali Kosh in the Zagros Mountains of southern Iran.

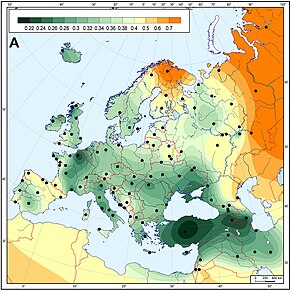

[79] Despite their scarcity, the Carbon-14 and archaeological age determinations for early Neolithic sites in Southern Asia exhibit remarkable continuity across the vast region from the Near East to the Indian Subcontinent, consistent with a systematic eastward spread at a speed of about 0.65 km/yr.

Food surpluses made possible the development of a social elite who were not otherwise engaged in agriculture, industry or commerce, but dominated their communities by other means and monopolized decision-making.

[97] Jared Diamond (in The World Until Yesterday) identifies the availability of milk and cereal grains as permitting mothers to raise both an older (e.g. 3 or 4 year old) and a younger child concurrently.

Diamond, in agreement with feminist scholars such as V. Spike Peterson, points out that agriculture brought about deep social divisions and encouraged gender inequality.

It also made possible nomadic pastoralism in semi arid areas, along the margins of deserts, and eventually led to the domestication of both the dromedary and Bactrian camel.

In their approximately 10,000 years of shared proximity with animals, such as cows, Eurasians and Africans became more resistant to those diseases compared with the indigenous populations encountered outside Eurasia and Africa.

According to bioarchaeological research, the effects of agriculture on dental health in Southeast Asian rice farming societies from 4000 to 1500 BP was not detrimental to the same extent as in other world regions.

[105] Jonathan C. K. Wells and Jay T. Stock have argued that the dietary changes and increased pathogen exposure associated with agriculture profoundly altered human biology and life history, creating conditions where natural selection favoured the allocation of resources towards reproduction over somatic effort.