First Chechen War

Despite the killing of Dudayev in a Russian airstrike in April 1996, the recapture of Grozny by separatists in August brought about the Khasavyurt Accord ceasefire and Russia–Chechnya Peace Treaty in 1997.

Despite intense resistance during the 1817–1864 Caucasian War, Imperial Russian forces defeated the Chechens, annexed their lands, and deported thousands to the Middle East throughout the latter half of the 19th century.

In 1944, on the orders of NKVD chief Lavrentiy Beria, more than 500,000 Chechens, the Ingush and several other North Caucasian people were ethnically cleansed and deported to Siberia and Central Asia.

Eventually, Soviet first secretary Nikita Khrushchev granted the Vainakh (Chechen and Ingush) peoples permission to return to their homeland and he restored their republic in 1957.

Eventually, in early 1994, Yeltsin signed a special political accord with Mintimer Shaeymiev, the president of Tatarstan, granting many of its demands for greater autonomy for the republic within Russia.

The storming caused the death of the head of Grozny's branch of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Vitaliy Kutsenko, who was defenestrated or fell while trying to escape.

After staging another coup d'état attempt in December 1993, the opposition organized themselves into the Provisional Council of the Chechen Republic as a potential alternative government for Chechnya, calling on Moscow for assistance.

Russia also suspended all civilian flights to Grozny while the aviation and border troops established a military blockade of the republic, and eventually unmarked Russian aircraft began combat operations over Chechnya.

The main attack was temporarily halted by the deputy commander of the Russian Ground Forces, General Eduard Vorobyov [ru], who then resigned in protest, stating that it is "a crime" to "send the army against its own people.

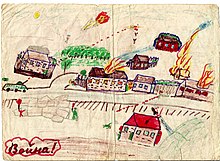

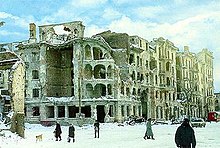

When the Russians besieged the Chechen capital, thousands of civilians died from a week-long series of air raids and artillery bombardments in the heaviest bombing campaign in Europe since the destruction of Dresden.

In what was dubbed the worst massacre in the war, the OMON and other federal forces killed up to 300 civilians while seizing the border village of Samashki on 7 April (several hundred more were detained and beaten or otherwise tortured).

[49] According to an estimate cited in a United States Army analysis report, between January and May 1995, when the Russian forces conquered most of the republic in the conventional campaign, their losses in Chechnya were approximately 2,800 killed, 10,000 wounded and more than 500 missing or captured.

The full-scale Russian attack led many of Dzhokhar Dudayev's opponents to side with his forces and thousands of volunteers to swell the ranks of mobile militant units.

Many others formed local self-defence militia units to defend their settlements in the case of federal offensive action, officially numbering 5,000–6,000 armed men in late 1995.

[54][55] In February 1996, federal and pro-Russian Chechen forces in Grozny opened fire on a massive pro-independence peace march of tens of thousands of people, killing a number of demonstrators.

On 6 March 1996, a group of Chechen fighters infiltrated Grozny and launched a three-day surprise raid on the city, taking most of it and capturing caches of weapons and ammunition.

[58] On April 16, a month after the initial conflict, Chechen fighters successfully carried out an ambush near Shatoy, wiping out an entire Russian armored column resulting in losses up to 220 soldiers killed in action.

[59] As military defeats and growing casualties made the war more and more unpopular in Russia, and as the 1996 presidential elections neared, Boris Yeltsin's government sought a way out of the conflict.

This announcement was followed by chaotic scenes of panic as civilians tried to flee before the army carried out its threat, with parts of the city ablaze and falling shells scattering refugee columns.

[66] According to Human Rights Watch, the campaign was "unparalleled in the area since World War II for its scope and destructiveness, followed by months of indiscriminate and targeted fire against civilians".

[71] A Chechen surgeon, Khassan Baiev, treated wounded in Samashki immediately after the operation and described the scene in his book:[72] Dozens of charred corpses of women and children lay in the courtyard of the mosque, which had been destroyed.

Leaving the village for the hospital in Grozny, I passed a Russian armored personnel carrier with the word SAMASHKI written on its side in bold, black letters.

For example, the government of Chuvashia passed a decree providing legal protection to soldiers from the republic who refused to participate in the Chechen war and imposed limits on the use of the federal army in ethnic or regional conflicts within Russia.

Tatarstan president Mintimer Shaimiev vocally opposed the war and appealed to Yeltsin to stop it and return conscripts, warning the conflict was at risk of expanding across the Caucasus.

[77] Some regional and local legislative bodies called for the prohibition on the use of draftees in quelling internal conflicts, while others demanded a total ban on the use of the armed forces in such situations.

[82] According to the World Peace Foundation at Tufts University, Estimates of the number of civilians killed range widely from 20,000 to 100,000, with the latter figure commonly referenced by Chechen sources.

A partial analysis of the list of 1,432 reported missing found that, as of 30 October 1996, at least 139 Chechens were still being forcibly detained by the Russian side; it was entirely unclear how many of these men were alive.

In February 1997, Russia also approved an amnesty for Russian soldiers and Chechen fighters alike who committed illegal acts in connection with the War in Chechnya between December 1994 and September 1996.

Little more than two years later, some of Maskhadov's former comrades-in-arms, led by field commanders Shamil Basayev and Ibn al-Khattab, launched an invasion of Dagestan in the summer of 1999 – and soon Russia's forces entered Chechnya again, marking the beginning of the Second Chechen War.

For example, Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev, who was generally regarded as a Western-leaning liberal, made the following remark when questioned about Russia's conduct during the war; "'Generally speaking, it is not only our right but our duty not to allow uncontrolled armed formations on our territory.