Polina Zherebtsova

She's the author of Ant in a Glass Jar, covering her childhood, adolescence and youth that witnessed two Chechen wars.

[1][2] She was born in a mixed ethnic family in Grozny, Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Republic, USSR.

She has been awarded the Janusz Korczak international prize in Jerusalem in two categories (narrative and documentary prose).

On 21 October 1999, the market in Grozny was shelled where she was helping her mother sell newspapers, and Polina was moderately injured.

Polina Zherebtsova has given interviews to the BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, has participated in literary festivals around the world.

Polina's maternal grandfather Zherebtsov Anatoly Pavlovich, with whom she had formed a friendship, worked in Grozny for more than 25 years as a TV journalist-cameraman.

In 2006, she has been awarded the Janusz Korczak international prize in Jerusalem in two categories (narrative and documentary prose).

[1] Because of her Russian surname and national strife, Polina was subjected to repeated insults at school.

In 1999 a new round of war in Grozny began in the North Caucasus, when Polina was 14 years old, which she describes in her diary.

While helping her mother trade in the central market in Grozny after high school, Polina was wounded in her leg on 21 October 1999, when the marketplace was shelled, as described in a preliminary report "The indiscriminate use of force by federal troops during the armed conflict in Chechnya in September–October 1999".

In Stavropol she transferred to the North Caucasus State Technical University, where she obtained her diploma for General Psychology in 2010.

Staff members of Solzhenitsyn's foundation helped Polina move to Moscow, but failed to publish the diaries.

[9] Threats were constantly set in the fact that I must stop writing on this subject if I want to live and if I don't want to have my family killed.

This is our land, we conquered and won it!” Consider: now you will have to share responsibility for those war crimes, which in the Caucasus are not the costs of “conquest”, but its essence.

How we buried our murdered neighbours under fire, having first covered the graves with branches so that the hungry dogs would not tear the bodies apart.

Publishers highly valued the diary, however, for a long time, one after another, they refused to print it, being "loyal to the government of modern Russia.-" Alissa de Carbonne, "Reuters", United Kingdom.

They hit the market where she worked with her mother, the streets she walked down daily, until Grozny was reduced to rubble, a hometown no longer recognisable.

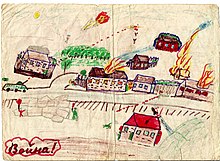

She filled dozens of diaries in a messy, scribbled cursive, sometimes embellished with doodles – bomb blasts that look like flowers, blocks of flats seen from a distance.

Miriam Elder, journalist, correspondent of The Guardian The girl born in 1985 in the Soviet Union, sees herself not Russian or Chechen, but a citizen of the world.

In the book, a lot of the episodes show that courage and perseverance inspire respect, but cowards do not survive.

In Russia, where the mother and daughter Zherebtsova get at the end of the book, they are considered "Chechen women", and they are again disenfranchised outcasts.

Alice Orlova, Miloserdie.ru These sheets from children's notebook are valuable: as evidence of surprising strength of the terrible events of the previous days, as the story of a person that existed inside a history textbook, as a document depicting the ruthless picture by a ruthless eye of a child, as a miraculously survived note of a contemporary.

But all these definitions are not accurate, these pages are about: the value of individual human life above any geopolitical considerations, national differences and global concepts, and the love and the will to live is stronger than a call of blood and explosions of shells.

The book is a real diary that Grozny's resident Polina Zherebtsova kept as a teenager in 1999–2002, at the height of the second Chechen war.

Polina kept Chechen diaries from 1994 to 2004: 10 years of fire, death, hunger, cold, diseases, humiliations, lies, betrayals, sadism – all, that together is denoted by four letters: "hell."

Elena Makeyenko, Siburbia.ru, “Diary as a way to survive” Diary of Polina Zherebtsova is valuable by the fact that it upsets the balance of the roles and calls for the voices of other characters: girls, women, old women, waiting for the death from young, strong Russian men in military uniforms.

Russians as "Germans", shooting in poor or old women or cackling over the girl who skedaddle from them on all fours – these paintings are not so easy to accept even for the most liberal and unblinkered consciousness, but it makes the effort of every reader to open "Diary" even more valuable.

Yes, we were beginning to travel abroad, to discover the world, to read a free press, to earn money.

But this will repeat itself over and over, I'm afraid, as long as we as a society, as a nation, as a country do not learn a simple truth: the defenceless people come first and foremost.

Polina Zherebtsova with her moral stance is much more convincing as a symbol of resistance to the fascist regime than Khodorkovsky and Navalny.