First Intifada

[7][8] It was motivated by collective Palestinian frustration over Israel's military occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip as it approached a twenty-year mark, having begun in the wake of the 1967 Arab–Israeli War.

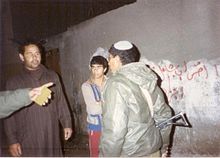

[14][15] There was graffiti, barricading,[16][17] and widespread throwing of stones and Molotov cocktails at the Israeli army and its infrastructure within the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Israeli countermeasures, which initially included the use of live rounds frequently in cases of riots, were criticized by Human Rights Watch as disproportionate, in addition to Israel's excessive use of lethal force.

[24] Intra-Palestinian violence was also a prominent feature of the Intifada, with widespread executions of an estimated 822 Palestinians killed as alleged Israeli collaborators (1988–April 1994).

According to Mubarak Awad, a Palestinian American clinical psychologist, the Intifada was a protest against Israeli repression including "beatings, shootings, killings, house demolitions, uprooting of trees, deportations, extended imprisonments, and detentions without trial".

[8] After Israel's capture of the West Bank, Jerusalem, Sinai Peninsula, and Gaza Strip from Jordan and Egypt in the Six-Day War in 1967, frustration grew among Palestinians in the Israeli-occupied territories.

[30] According to Israeli historian and diplomat Shlomo Ben-Ami in his book Scars of War, Wounds of Peace, the Intifada was also a rebellion against the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

[31] The Israeli Labor Party's Yitzhak Rabin, then Defense Minister, added deportations in August 1985 to Israel's "Iron Fist" policy of cracking down on Palestinian nationalism.

[32] This, which led to 50 deportations in the following 4 years,[33] was accompanied by economic integration and increasing Israeli settlements, such that the Jewish settler population in the West Bank alone nearly doubled from 35,000 in 1984 to 64,000 in 1988, reaching 130,000 by the mid-nineties.

[34] Referring to the developments, Israeli minister of Economics and Finance, Gad Ya'acobi, stated that "a creeping process of de facto annexation" contributed to a growing militancy in Palestinian society.

"[36] While the catalyst for the First Intifada is generally dated to a truck incident involving several Palestinian fatalities at the Erez Crossing in December 1987,[37] Mazin Qumsiyeh argues, against Donald Neff, that it began with multiple youth demonstrations earlier in the preceding month.

[37][39][40] Mass demonstrations had occurred a year earlier when, after two Gaza students at Birzeit University had been shot by Israeli soldiers on campus on 4 December 1986, the Israelis responded with harsh punitive measures, involving summary arrest, detention, and systematic beatings of handcuffed Palestinian youths, ex-prisoners and activists, some 250 of whom were detained in four cells inside a converted army camp, known popularly as Ansar 11, outside Gaza City.

Over the summer the IDF's Lieutenant Ron Tal, who was responsible for guarding detainees at Ansar 11, was shot dead at point-blank range while stuck in a Gaza traffic jam.

[42] Some days later, a 17-year-old schoolgirl, Intisar al-'Attar, was shot in the back while in her schoolyard in Deir al-Balah by a settler in the Gaza Strip, who claimed the girl had been throwing stones.

Rumours swept the camp that the incident was an act of intentional retaliation for the stabbing to death of an Israeli businessman, killed while shopping in Gaza two days earlier.

[53][54][55][56] On 9 December, several popular and professional Palestinian leaders held a press conference in West Jerusalem with the Israeli League for Human and Civil Rights in response to the deterioration of the situation.

Youths took control of neighbourhoods, closed off camps with barricades of garbage, stone and burning tires, meeting soldiers who endeavoured to break through with petrol bombs.

The Israeli security forces used the full panoply of crowd control measures to try and quell the disturbances: cudgels, nightsticks, tear gas, water cannons, rubber bullets, and live ammunition.

Since initially a high proportion of those killed were civilians and youths, Yitzhak Rabin adopted a fallback policy of 'might, power and beatings'.

"[73] In an article in the London Review of Books, John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt asserted that IDF soldiers were given truncheons and encouraged to break the bones of Palestinian protesters.

During Ramadan, many camps in Gaza were placed under curfew for weeks, impeding residents from buying food, and Al-Shati, Jabalya and Burayj were subjected to saturation bombing by tear gas.

The PLO and its chairman Yassir Arafat had also decided on an unarmed strategy, in the expectation that negotiations at that time would lead to an agreement with Israel.

[8] Pearlman attributes the non-violent character of the uprising to the movement's internal organization and its capillary outreach to neighborhood committees that ensured that lethal revenge would not be the response even in the face of Israeli state repression.

[82] Hamas and Islamic Jihad cooperated with the leadership at the outset, and throughout the first year of the uprising conducted no armed attacks, except for the stabbing of a soldier in October 1988, and the detonation of two roadside bombs, which had no impact.

[83] Leaflets publicizing the Intifada's aims demanded the complete withdrawal of Israel from the territories it had occupied in 1967: the lifting of curfews and checkpoints; it appealed to Palestinians to join in civic resistance, while asking them not to employ arms, since military resistance would only invite devastating retaliation from Israel; it also called for the establishment of the Palestinian state on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, abandoning the standard rhetorical calls, still current at the time, for the "liberation" of all of Palestine.

[84] On 16 April 1988, a leader of the PLO, Khalil al-Wazir, nom de guerre Abu Jihad or 'Father of the Struggle', was assassinated in Tunis by an Israeli commando squad.

"[88] When time in prison did not stop the activists, Israel crushed the boycott by imposing heavy fines and seizing and disposing of equipment, furnishings, and goods from local stores, factories and homes.

[90] The Israeli state apparatus carried out contradictory and conflicting policies that were seen to have injured Israel's own interests, such as the closing of educational establishments (putting more youths onto the streets) and issuing the Shin Bet list of collaborators.

At the meeting of the Palestine National Council in Algiers in mid-November 1988, Arafat won a majority for the historic decision to recognize Israel's legitimacy, accept all the relevant UN resolutions going back to 29 November 1947, and adopt the principle of a two-state solution based on 1967 borders.

"[8] The founder of the Palestinian Center for the Study of Nonviolence, Jerusalem-born Mubarak Awad, played a major role in advocating for and organizing civil disobedience campaigns against the Israel's occupation in the years prior to the First Intifada.