First Red Scare

Progressive Era Repression and persecution Anti-war and civil rights movements Contemporary Active Defunct Publications Works Personal ideologies Nationalisms The first Red Scare was a period during the early 20th-century history of the United States marked by a widespread fear of far-left movements, including Bolshevism and anarchism, due to real and imagined events; real events included the Russian 1917 October Revolution, German Revolution of 1918–1919, and anarchist bombings in the U.S. At its height in 1919–1920, concerns over the effects of radical political agitation in American society and the alleged spread of socialism, communism, and anarchism in the American labor movement fueled a general sense of concern.

Bolshevism and the threat of a communist-inspired revolution in the U.S. became the overriding explanation for challenges to the social order, even for such largely unrelated events as incidents of interracial violence during the Red Summer of 1919.

[20] The Committee's hearings into Bolshevik propaganda, conducted from February 11 to March 10, 1919, developed an alarming image of Bolshevism as an imminent threat to the U.S. government and American values.

"[24] The senators were particularly interested in how Bolshevism had united many disparate elements on the left, including anarchists and socialists of many types,[25] "providing a common platform for all these radical groups to stand on".

[26] Senator Knute Nelson, Republican of Minnesota, responded by enlarging Bolshevism's embrace to include an even larger segment of political opinion: "Then they have really rendered a service to the various classes of progressives and reformers that we have here in this country.

One extended headline in February read:[29] Bolshevism Bared by R. E. Simmons; Former Agent in Russia of Commerce Department Concludes his Story to Senators Women are 'Nationalized' Official Decrees Reveal Depths of Degradation to Which They are Subjected by Reds Germans Profit by Chaos Factories and Mills are Closed and the Machinery Sold to Them for a Song On the release of the final report, newspapers printed sensational articles with headlines in capital letters: "Red Peril Here", "Plan Bloody Revolution", and "Want Washington Government Overturned".

Fatalities included a New York City night watchman, William Boehner,[36][37][39] and one of the bombers, Carlo Valdinoci, a Galleanist radical who died in spectacular fashion when the bomb he placed at the home of Attorney General Palmer exploded in his face.

[41] All of the bombs were delivered with pink flyers bearing the title "Plain Words" that accused the intended victims of waging class war and promised: "We will destroy to rid the world of your tyrannical institutions.

Leftists protesting the imprisonment of Eugene V. Debs and promoting the campaign of Charles Ruthenberg, the Socialist candidate for mayor, planned to march through the center of the city.

[51] In mid-summer, in the middle of the Chicago riots, a "federal official" told the New York Times that the violence resulted from "an agitation, which involves the I.W.W., Bolshevism and the worst features of other extreme radical movements".

He supported that claim with copies of negro publications that called for alliances with leftist groups, praised the Soviet regime, and contrasted the courage of jailed Socialist Eugene V. Debs with the "school boy rhetoric" of traditional black leaders.

The Times characterized the publications as "vicious and apparently well financed," mentioned "certain factions of the radical Socialist elements", and reported it all under the headline: "Reds Try to Stir Negroes to Revolt".

[56] In mid-October, government sources again provided the New York Times with evidence of Bolshevist propaganda targeting America's black communities that was "paralleling the agitation that is being carried on in industrial centres of the North and West, where there are many alien laborers".

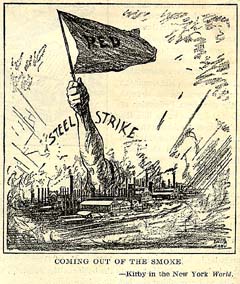

The public, fed by lurid press accounts and hyperbolic political observers, viewed the strike with a degree of alarm out of proportion to the events, which ultimately produced only about $35,000 of property damage.

[69] In response to the strikes, which was marked heavily by the Red Scare, rhetoric accusing tenant leaders of being Bolsheviks and comments that claimed a fear that there would be a mass uprising were commonly invoked by political officials at the time.

Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer invoked the Lever Act, a wartime measure that made it a crime to interfere with the production or transportation of necessities.

On October 17, 1919, just a year after the Immigration Act of 1918 had expanded the definition of aliens that could be deported, the U.S. Senate demanded Palmer explain his failure to move against radicals.

Even the captain only learned his final destination while in Kiel harbor for repairs, since the State Department found it difficult to make arrangements to land in Latvia.

The text was purportedly brought to the United States by a Russian army officer in 1917; it was translated into English by Natalie de Bogory (personal assistant of Harris A. Houghton, an officer of the Department of War) in June 1918,[111] and White Russian expatriate Boris Brasol soon circulated it in American government circles, specifically diplomatic and military, in typescript form,[112] It also appeared in 1919 in the Public Ledger as a pair of serialized newspaper articles.

[126] Other films used one feature or another of radical philosophy as the key plot point: anarchist violence (The Burning Question),[127] assassination and devotion to the red flag (The Volcano),[128] utopian vision (Bolshevism on Trial).

[130] As a promotion device, the April 15, 1919, issue of Moving Picture World suggested staging a mock radical demonstration by hanging red flags around town and then have actors in military uniforms storm in to tear them down.

With that legislation rendered inoperative by the end of World War I, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, supported by President Wilson,[140] waged a public campaign in favor of a peacetime version of the Sedition Act without success.

[141][142] He sent a circular outlining his rationale to newspaper editors in January 1919, citing the dangerous foreign-language press and radical attempts to create unrest in African American communities.

Though agents in the GID knew there was a gap between what the radicals promised in their rhetoric and what they were capable of accomplishing, they nevertheless told Palmer they had evidence of plans for an attempted overthrow of the U.S. government on May Day 1920.

Palmer issued his own warning on April 29, 1920, claiming to have a "list of marked men"[149] and said domestic radicals were "in direct connection and unison" with European counterparts with disruptions planned for the same day there.

[151] The Rocky Mountain News asked the Attorney General to cease his alerts: "We can never get to work if we keep jumping sideways in fear of the bewiskered Bolshevik.

They help to frighten capital and demoralize business, and to make timid men and women jumpy and nervous.Palmer's embarrassment buttressed Louis Freeland Post's position in opposition to the Palmer raids when he testified before a Congressional Committee on May 7–8.

[155] In testimony before Congress on May 7–8, Louis Freeland Post defended his release of hundreds seized in Palmer's raids so successfully that attempts to impeach or censure him ended.

[157] In June, Massachusetts Federal District Court Judge George W. Anderson ordered the discharge of twenty more arrested aliens and effectively ended the possibility of additional raids.

"[159] Leaders of industry voiced similar sentiments, including Charles M. Schwab of Bethlehem Steel, who thought Palmer's activities created more radicals than they suppressed, and T. Coleman du Pont who called the Justice Department's work evidence of "sheer Red hysteria".

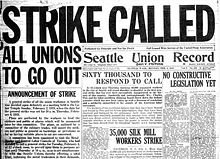

Published September 14, 1919

![Scan of a newspaper front page. The word "Leger", part of the title, is visible at the top. The rest, so far as legible in this image, reads: RED "BIBLE" COUNSELS APPEAL TO VIOLENCE / "Right is Might" is Cardinal text of Doctrines Expounded in Guidebook of World Revolutionists / Bolshevist Propaganda Seized / [illegible byline] / Boston, Oct. 26—Pamphlets and other I.W.W. literature containing rules and instructions for burning buildings and shooting from concealed places have been seized by army intelligence officers here. The "Red" literature was discovered by military authorities. An organized campaign is being waged by the War Department against Bolshevist propagandists, anarchists and the I.W.W. / By Paul W. Ackermann / Public Ledger Correspondent](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c6/Red_Bible_-_Carl_W_Ackerman_-_October_27%2C_1919.jpg/220px-Red_Bible_-_Carl_W_Ackerman_-_October_27%2C_1919.jpg)