Finnish Civil War

[9] From 1809 to 1898, a period called the Pax Russica,[10] the peripheral authority of the Finns gradually increased, and relations between Russian Empire and Grand Duchy of Finland were exceptionally peaceful for a many years.

All this encouraged Finnish nationalism and cultural unity through the birth of the Fennoman movement, which bound the Finns to the domestic administration and led to the idea that the Grand Duchy was an increasingly autonomous state ruled by the Russian Empire.

The strengthened, pan-slavist central power tried to unite the "Russian Multinational Dynastic Union" as the military and strategic situation of Russia became more perilous due to the rise of Germany and Japan.

Finns called the increased military and administrative control, "the First Period of Oppression", and for the first time Finnish politicians drew up plans for disengagement from Russia or full sovereignty for Finland.

The position of rural workers worsened after the end of the nineteenth century, as farming became more efficient and market-oriented, and the development of industry was insufficiently vigorous to fully utilise the rapid population growth of the countryside.

[14] Between 1870 and 1916 industrialisation gradually improved social conditions and the self-confidence of workers, but while the standard of living of the common people rose in absolute terms, the rift between rich and poor deepened markedly.

[16] Despite their obligations as obedient, peaceful and non-political inhabitants of the Grand Duchy (who had, only a few decades earlier, accepted the class system as the natural order of their life), the commoners began to demand their civil rights and citizenship in Finnish society.

Since the end of the 19th century, the Grand Duchy had become a vital source of raw materials, industrial products, food and labour for the growing Imperial Russian capital Petrograd (modern Saint Petersburg), and World War I emphasised that role.

The collapse of Russia induced a chain reaction of disintegration, starting from the government, military and economy, and spreading to all fields of society, such as local administration, workplaces and to individual citizens.

In theory, the Senate consisted of a broad national coalition, but in practice (with the main political groups unwilling to compromise and top politicians remaining outside of it), it proved unable to solve any major Finnish problem.

In the aftermath of these events, the "Law of Supreme Power" was overruled and the social democrats eventually backed down; more Russian troops were sent to Finland and, with the co-operation and insistence of the Finnish conservatives, Parliament was dissolved and new elections announced.

'protection corps') and the later White Guards (Finnish: valkokaartit; Swedish: vita gardet) were organised by local men of influence: conservative academics, industrialists, major landowners, and activists.

Economically, the Grand Duchy of Finland benefited from having an independent domestic state budget, a central bank with national currency, the markka (deployed 1860), and customs organisation and the industrial progress of 1860–1916.

[47] In December 1917, Lenin was under intense pressure from the Germans to conclude peace negotiations at Brest-Litovsk, and the Bolsheviks' rule was in crisis, with an inexperienced administration and the demoralised army facing powerful political and military opponents.

The Red Guards controlled the area to the south, including nearly all the major towns and industrial centres, along with the largest estates and farms with the highest numbers of crofters and tenant farmers.

In February 1918, the Whites would have received an aircraft donation of a reconnaissance and training plane from Sweden, the NAB Type 9 Albatros, however its transport to Vaasa was stopped when the ferry's engine failed at Jakobstad.

The Civil War was fought primarily along railways; vital means for transporting troops and supplies, as well for using armoured trains, equipped with light cannons and heavy machine guns.

White Guard leaders faced a similar problem when drafting young men to the army in February 1918: 30,000 obvious supporters of the Finnish labour movement never showed up.

The Finnish Civil War opened a low-cost access route to Fennoscandia, where the geopolitical status was altered as a Royal Navy squadron occupied the Soviet harbour of Murmansk by the Arctic Ocean on 9 March 1918.

The leader of the German war effort, General Erich Ludendorff, wanted to keep Petrograd under threat of attack via the Viipuri-Narva area and to install a German-led monarchy in Finland.

On 3 April 1918, the 10,000-strong Baltic Sea Division (German: Ostsee-Division), led by General Rüdiger von der Goltz, launched the main attack at Hanko, west of Helsinki.

The German naval squadron led by Vice Admiral Hugo Meurer blocked the city harbour, bombarded the southern town area, and landed Seebataillon marines at Katajanokka.

[106] Combined with the severe food shortages caused by the Civil War, mass imprisonment led to high mortality rates in the prison camps, and the catastrophe was compounded by the angry, punitive and uncaring mentality of the victors.

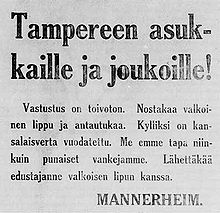

[111] Among the Reds in particular, the loss of the war caused such bitterness that some of those who fled behind the eastern border tried to carry out the assassination of General Mannerheim during a White Guard's victory parade of Tampere in 1920, with poor results.

The republicans argued that the 1772 law lost validity in the February Revolution, that the authority of the Russian tsar was assumed by the Finnish Parliament on 15 November 1917, and that the Republic of Finland had been adopted on 6 December that year.

After the power struggle of 1917 and the bloody civil war, the former Fennomans and the social democrats who had supported "ultra-democratic" means in Red Finland declared a commitment to revolutionary Bolshevism–communism and to the dictatorship of the proletariat, under the control of Lenin.

[124] In April 1918, the leading Finnish social liberal and the eventual first President of Finland, Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg wrote: "It is urgent to get the life and development in this country back on the path that we had already reached in 1906 and which the turmoil of war turned us away from."

In the end, many of the moderate Finnish conservatives followed the thinking of National Coalition Party member Lauri Ingman, who wrote in early 1918: "A political turn more to the right will not help us now, instead it would strengthen the support of socialism in this country.

In poetry, Bertel Gripenberg, who had volunteered for the White Army, celebrated its cause in "The Great Age" (Swedish: Den stora tiden) in 1928 and V. A. Koskenniemi in "Young Anthony" (Finnish: Nuori Anssi) in 1918.

Lauri Viita's book "Scrambled Ground" (Finnish: Moreeni) from 1950 presented the life and experiences of a worker family in the Tampere of 1918, including a point of view from outsiders to the Civil War.