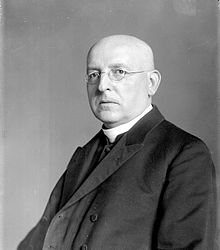

First Schober government

The main challenges facing the first Schober government were Austria's lack of money, rampant inflation, and dependence on imports the country became increasingly unable to afford.

The government was in desperate need of credit, but loans would not be forthcoming until Austria assuaged fears among the Allies of World War I that it might attempt to defy the Treaty of Saint-Germain.

When Schober managed to open lines of credit through confirming Austria's commitment to independence in the Treaty of Lana, the People's Party forced his resignation.

The poor tax base and brutal trade imbalance prompted the Austrian government to print too much money.

Although Hungary swiftly and roundly rebuffed the would-be king, the incident put additional strain on Austro-Czechoslovak relations.

[2] The fourteen parties in Austria's Constituent Assembly had radically different visions regarding the constitutional, territorial, and economic future of their demoralized, impoverished rump state.

Austrians began to warm to the idea of a "cabinet of civil servants" ("Beamtenkabinett"), a government of senior career bureaucrats who would be loyal to the country and not to any particular ideological camp.

A pool of highly educated middle-aged administrators who counted sober professionalism as an important aspect of their self-image stood ready to be tapped.

Seipel, however, was reluctant to assume the chancellorship because of the difficult decisions and general hardship he knew still lay ahead; he wanted someone else to do the dirty work.

[7][8] The Republic of German-Austria had been proclaimed with the understanding that it would eventually join the German Reich, a vision shared by a clear majority of its population at the time.

[9][10][11] In early 1921, several provincial governments hatched plans to break away from Austria and join Germany on their own; preparations for local referendums were made.

The Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Education, historically independent but merged since the second Renner government, were not yet separated again, but in addition to the actual minister there was a state secretary (Staatssekretär) in charge of education affairs (betraut mit der Leitung der Angelegenheiten des Unterrichts und Kultus).

Schober also expressed his hope that Beneš would find it in his heart to help open up lines of credit for Austria, by putting in a good word for the country "in Paris and London".

On August 10, 1921, Beneš and Tomáš Masaryk, the Czechoslovak president, traveled to Hallstatt and negotiated a compact of mutual understanding and support with their Austrian counterparts, Schober and Michael Hainisch.

In the Political Agreement between the Republic of Austria and the Czechoslovak Republic (Politisches Abkommen zwischen der Republik Österreich und der Tschechoslowakischen Republik), the two countries promised each other to honor the Treaty of Saint-Germain, to respect each other's borders, to support each other diplomatically, and to remain neutral if either of them should be attacked by a third party.

[17] The agreement was signed on December 16 during a return visit of the Austrians to Lány Castle, the summer seat of the Czechoslovak president.

Adolf Hitler traveled from Munich to Vienna to rail against the treaty in front of some six hundred sympathizers, a notable early appearance.