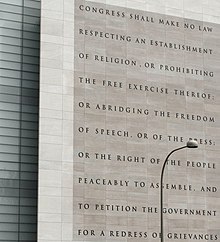

First Amendment to the United States Constitution

[5] Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

In 1776, the second year of the American Revolutionary War, the Virginia colonial legislature passed a Declaration of Rights that included the sentence "The freedom of the press is one of the greatest bulwarks of liberty, and can never be restrained but by despotic Governments."

[20]In his dissenting opinion in McGowan v. Maryland (1961), Justice William O. Douglas illustrated the broad protections offered by the First Amendment's religious liberty clauses: The First Amendment commands government to have no interest in theology or ritual; it admonishes government to be interested in allowing religious freedom to flourish—whether the result is to produce Catholics, Jews, or Protestants, or to turn the people toward the path of Buddha, or to end in a predominantly Moslem nation, or to produce in the long run atheists or agnostics.

At one time, it was thought that this right merely proscribed the preference of one Christian sect over another, but would not require equal respect for the conscience of the infidel, the atheist, or the adherent of a non-Christian faith such as Islam or Judaism.

[36] In Larkin v. Grendel's Den, Inc. (1982) the Supreme Court stated that "the core rationale underlying the Establishment Clause is preventing 'a fusion of governmental and religious functions,' Abington School District v. Schempp, 374 U. S. 203, 374 U. S. 222 (1963).

"[51] In a series of cases in the first decade of the 2000s—Van Orden v. Perry (2005),[52] McCreary County v. ACLU (2005),[53] and Salazar v. Buono (2010)[54]—the Court considered the issue of religious monuments on federal lands without reaching a majority reasoning on the subject.

But the "exercise of religion" often involves not only belief and profession but the performance of (or abstention from) physical acts: assembling with others for a worship service, participating in sacramental use of bread and wine, proselytizing, abstaining from certain foods or certain modes of transportation.

[102] The Supreme Court explained that "[o]fficial action that targets religious conduct for distinctive treatment cannot be shielded by mere compliance with the requirement of facial neutrality" and "[t]he Free Exercise Clause protects against governmental hostility which is masked as well as overt.

The principle that government, in pursuit of legitimate interests, cannot in a selective manner impose burdens only on conduct motivated by religious belief is essential to the protection of the rights guaranteed by the Free Exercise Clause.

[111] The Supreme Court decided in light of this in Tanzin v. Tanvir (2020) that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act's express remedies provision permits litigants, when appropriate, to obtain money damages against federal officials in their individual capacities.

"[114][115] The Supreme Court in Estate of Thornton v. Caldor, Inc. (1985) echoed this statement by quoting Judge Learned Hand from his 1953 case Otten v. Baltimore & Ohio R. Co., 205 F.2d 58, 61 (CA2 1953): "The First Amendment ... gives no one the right to insist that, in pursuit of their own interests others must conform their conduct to his own religious necessities.

[121] In Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer (2017),[122] the Court ruled that denying a generally available public benefit on account of the religious nature of an institution violates the Free Exercise Clause.

[137] In Stanley v. Georgia (1969), the Supreme Court stated that the First Amendment protects the right to receive information and ideas, regardless of their social worth, and to be generally free from governmental intrusions into one's privacy and control of one's own thoughts.

[141] In Bond v. Floyd (1966), a case involving the Constitutional shield around the speech of elected officials, the Supreme Court declared that the First Amendment central commitment is that, in the words of New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), "debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open".

v. Mosley (1972), Chief Justice Warren E. Burger said: Numerous holdings of this Court attest to the fact that the First Amendment does not literally mean that we "are guaranteed the right to express any thought, free from government censorship."

[144] The United States Constitution protects, according to the Supreme Court in Stanley v. Georgia (1969), the right to receive information and ideas, regardless of their social worth, and to be generally free from governmental intrusions into one's privacy and control of one's thoughts.

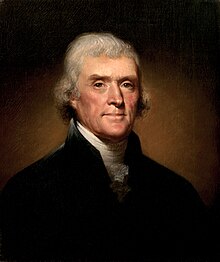

[149] In the late 1790s, the lead author of the speech and press clauses, James Madison, argued against narrowing this freedom to what had existed under English common law: The practice in America must be entitled to much more respect.

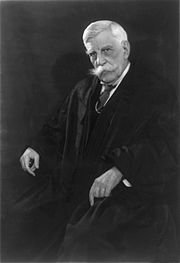

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., writing for the Court, explained that "the question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.

[165] On June 16, 1918, Eugene V. Debs, a political activist, delivered a speech in Canton, Ohio, in which he spoke of "most loyal comrades were paying the penalty to the working class—these being Wagenknecht, Baker and Ruthenberg, who had been convicted of aiding and abetting another in failing to register for the draft.

[163] The Supreme Court denied a number of Free Speech Clause claims throughout the 1920s, including the appeal of a labor organizer, Benjamin Gitlow, who had been convicted after distributing a manifesto calling for a "revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat".

[175][176][177] The importance of freedom of speech in the context of "clear and present danger" was emphasized in Terminiello v. City of Chicago (1949)[178] where the Supreme Court noted that the vitality of civil and political institutions in society depends on free discussion.

The Court affirmed the constitutionality of limits on campaign contributions, saying they "serve[d] the basic governmental interest in safeguarding the integrity of the electoral process without directly impinging upon the rights of individual citizens and candidates to engage in political debate and discussion.

The Court overruled Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce (1990),[223] which had upheld a state law that prohibited corporations from using treasury funds to support or oppose candidates in elections did not violate the First or Fourteenth Amendments.

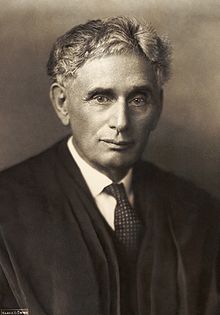

[334] Justice Felix Frankfurter stated in a concurring opinion in another case succinctly: "[T]he purpose of the Constitution was not to erect the press into a privileged institution but to protect all persons in their right to print what they will as well as to utter it.

The Constitution specifically selected the press, which includes not only newspapers, books, and magazines, but also humble leaflets and circulars, see Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444, to play an important role in the discussion of public affairs.

Suppression of the right of the press to praise or criticize governmental agents and to clamor and contend for or against change, which is all that this editorial did, muzzles one of the very agencies the Framers of our Constitution thoughtfully and deliberately selected to improve our society and keep it free.

Hughes quoted Madison in the majority decision, writing, "The impairment of the fundamental security of life and property by criminal alliances and official neglect emphasizes the primary need of a vigilant and courageous press.

[340] This exception was a key point in another landmark case four decades later: New York Times Co. v. United States (1971),[341] in which the administration of President Richard Nixon sought to ban the publication of the Pentagon Papers, classified government documents about the Vietnam War secretly copied by analyst Daniel Ellsberg.

Justice Brennan, drawing on Near in a concurrent opinion, wrote that "only governmental allegation and proof that publication must inevitably, directly, and immediately cause the occurrence of an evil kindred to imperiling the safety of a transport already at sea can support even the issuance of an interim restraining order."

"[365] In two 1960s decisions collectively known as forming the Noerr-Pennington doctrine,[i] the Court established that the right to petition prohibited the application of antitrust law to statements made by private entities before public bodies: a monopolist may freely go before the city council and encourage the denial of its competitor's building permit without being subject to Sherman Act liability.