Clear and present danger

Clear and present danger was a doctrine adopted by the Supreme Court of the United States to determine under what circumstances limits can be placed on First Amendment freedoms of speech, press, or assembly.

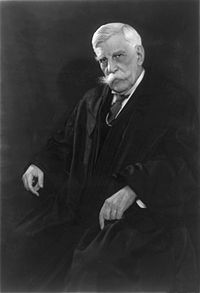

In the 1919 case Schenck v. United States, the Supreme Court held that an antiwar activist did not have a First Amendment right to advocate draft resistance.

When a nation is at war, many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight, and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right.In Frohwerk v. United States (1919) Justice Holmes summarized comments critical of U.S. wartime policies written by a newspaperman and stated about these comments the following: "It may be that all this might be said or written even in time of war in circumstances that would not make it a crime.

"[5] This statement "represents an important addendum to the original explication of the clear and present danger test in that it specifies that even during war, courts should regard criticism of government policies and officials as protected speech.

[8][9] The Court continued to use the bad tendency test during the early 20th century in cases such as 1919's Abrams v. United States, which upheld the conviction of antiwar activists who passed out leaflets encouraging workers to impede the war effort.

[20] The importance of freedom of speech in the context of "clear and present danger" was emphasized in Terminiello v. City of Chicago (1949),[21] in which the Supreme Court noted that the vitality of civil and political institutions in society depends on free discussion.

Judge Learned Hand considered the clear and present danger test, but his opinion adopted a balancing approach similar to that suggested in American Communications Association v.

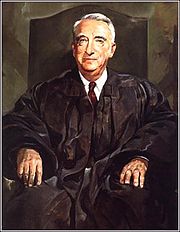

Chief Justice Fred Vinson's opinion stated that the First Amendment does not require that the government must wait "until the putsch is about to be executed, the plans have been laid and the signal is awaited" before it interrupts seditious plots.

More we cannot expect from words.Following Schenck v. United States, "clear and present danger" became both a public metaphor for First Amendment speech[29][30] and a standard test in cases before the Court where a United States law limits a citizen's First Amendment rights; the law is deemed to be constitutional if it can be shown that the language it prohibits poses a "clear and present danger".

However, the "clear and present danger" criterion of the Schenck decision was replaced in 1969 by Brandenburg v. Ohio,[31] and the test refined to determining whether the speech would provoke an "imminent lawless action".

[33] Bad tendency was a far more ambiguous standard where speech could be punished even in the absence of identifiable danger, and as such was strongly opposed by the fledgling American Civil Liberties Union and other libertarians of the time.