Fiscal policy of the Philippines

[1] In the Philippines, this is characterized by continuous and increasing levels of debt and budget deficits, though there were improvements in the last few years of the first decade of the 21st century.

Fiscal policy during the Marcos administration was primarily focused on indirect tax collection and on government spending on economic services and infrastructure development.

During the Arroyo administration, the Expanded Value Added Tax Law was enacted, national debt-to-GDP ratio peaked, and underspending on public infrastructure and other capital expenditures was observed.

9504 (passed by then-President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo) exempted minimum wage earners from paying income taxes.

Exemptible from the E-VAT are:[11] Second to the BIR in terms of revenue collection, the Bureau of Customs (BOC) imposes tariffs and duties on all items imported into the Philippines.

[13] The Bureau of the Treasury (BTr) manages the finances of the government, by attempting to maximize revenue collected and minimize spending.

According to the Department of Finance, the country has recently reduced dependency on external sources to minimize the risks caused by changes in the global exchange rates.

The Philippine government has also entered talks with other economic entities, like the ASEAN Finance Ministers Meeting (AFMM), ASEAN+3 Finance Ministers Meeting (AFMM+3), Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), and ASEAN Single-Window Technical Working Group (ASW-TWG), in order to strengthen the countries' and the region's debt management efforts.

Government expenditure for economic services peaked during this period, focusing mainly on infrastructure development, with about 33% of the budget spent on capital outlays.

Under a revolutionary government, Aquino exercised executive and legislative powers and overhauled the weak tax system with virtually no resistance.

To minimize revenue loss and preserve the relative burden of individuals, ceilings on allowable business deductions were proposed and adopted.

Personal exemptions were increased to adjust for inflation and to eliminate the taxation of those earning below the poverty threshold income.

The imposition of an income tax on franchise grantees put this previously favored group on an equal footing with similarly situated individuals or firms.

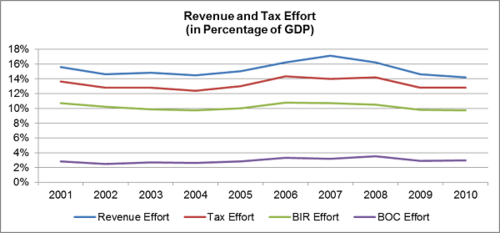

[22][23] The Arroyo administration in 2001 inherited a poor fiscal position that was attributed to weakening tax effort (still resulting from the 1997 CTRP) and rising debt servicing costs (due to peso depreciation).

Large fiscal deficits and heavy losses for monitored government corporations lingered from 2001 to 2004 as her caretaker administration struggled to reverse downward trends.

The cost of medicines was brought down by as much as 50% as a result of the Cheaper Medicines Act and the opening of Botikas ng Bayan and Botikas ng Barangay, while the ground-breaking conditional cash transfers (CCT) program was adapted from Latin America to stimulate positive behaviors among the poor.

Much of the fuel for government activism came from an expanded value-added tax (from 10% to 12%) in 2005 (see final reports of various Cabinet agencies concerned), which with other fiscal reforms paved the way for successive sovereign credit rating upgrades by the time Arroyo stepped down in June 2010.

These fiscal reforms complemented conservative liquidity management by the Central Bank, allowing the peso, for the first time ever, to close even stronger at the end of a presidential term than at the start.