Five Points, Manhattan

[8] Fed by an underground spring, it was located in a valley, with Bayard's Mount (at 110 feet or 34 metres, the tallest hill in lower Manhattan) to the northeast.

These businesses included Coulthards Brewery, Nicholas Bayard's slaughterhouse on Mulberry Street (which was nicknamed "Slaughterhouse Street"),[11] numerous tanneries on the southeastern shore, and the pottery works of German immigrants Johan Willem Crolius and Johan Remmey on Pot Bakers Hill on the south-southwestern shore.

Pierre Charles L'Enfant proposed cleaning the pond and making it a centerpiece of a recreational park, around which the residential areas of the city could grow.

The buried vegetation began to release methane gas (a byproduct of decomposition) and the area, in a natural depression, lacked adequate storm sewers.

Houses shifted on their foundations, the unpaved streets were often buried in a foot of mud mixed with human and animal excrement, and mosquitoes bred in the stagnant pools created by the poor drainage.

Most middle and upper class inhabitants fled the area, leaving the neighborhood open to poor immigrants who began arriving in the early 1820s.

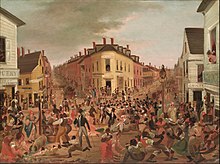

[14] At the height of Five Points' inhabitation, only parts of London's East End were equivalent in the western world for population density, child and infant mortality, disease, violent crime, unemployment, prostitution, and other classic problems of the urban destitute.

Infectious diseases, such as cholera, tuberculosis, typhus, and malaria and yellow fever, had plagued New York City since the Dutch colonial era.

The lack of scientific knowledge, sanitation systems, the numerous overcrowded dwellings, and absence of even rudimentary health care made impoverished areas such as Five Points ideal for the development and spread of these diseases.

[25] With no understanding of disease vectors or transmission, some observers believed that these epidemics were due to the immorality of residents of the slum: Every day's experience gives us assurance of the safety of the temperate and prudent, who are in circumstances of comfort ….

Their deeper origins[26] lay in the combination of nativism and abolitionism among Protestants, who had controlled the city since the American Revolution, and the fear and resentment of blacks among the growing numbers of Irish immigrants, who competed with them for jobs and housing.

Historian Tyler Anbinder says the "dead rabbits" name "so captured the imagination of New Yorkers that the press continued to use it despite the abundant evidence that no such club or gang existed".

Anbinder notes that, "for more than a decade, 'Dead Rabbit' became the standard phrase by which city residents described any scandalously riotous individual or group.

"[27] Brick-bats, stones and clubs were flying thickly around, and from the windows in all directions, and the men ran wildly about brandishing firearms.

The Daily National Intelligencer of July 8, 1857, estimated that between 800 and 1,000 gang members took part in the riots, along with several hundred others who used the disturbance to loot the Bowery area.

In 1853, the parish relocated to the corner of Mott and Cross streets, when they purchased the building of the Zion Protestant Episcopal Church (c.1801) from its congregation, which moved uptown.

The first call for clearing the slums of Five Points through wholesale demolition came in 1829 from merchants who maintained businesses in close proximity to the neighborhood.

[29] That the place known as "Five points" has long been notorious... as being the nursery where every species of vice is conceived and matured; that it is infested by a class of the most abandoned and desperate character.... [They] are abridged from enjoying themselves in their sports, from the apprehension... that they may be enticed from the path of rectitude, by being familiarized with vice; and thus advancing step by step, be at last swallowed up in this sink of pollution, this vortex of irremediable infamy....

In conclusion your Committee remark, that this hot-bed of infamy, this modern Sodom, is situated in the very heart of your City, and near the centre of business and of respectable population....

[note 1] A major effort was made to clear the Old Brewery on Cross Street, described as "a vast dark cave, a black hole into which every urban nightmare and unspeakable fear could be projected.

The Christian Advocate, also called The Christian Advocate and Journal, a weekly New York newspaper published by the Methodist Episcopal Church, reported on the ongoing project in October 1853: In a meeting held in Metropolitan Hall, in December 1851, such convincing proof was given of the public interest in this project, that the resolution was passed by the Executive Committee to purchase the Old Brewery.

[32] In the west and south, it is occupied by major federal, state, and city administration buildings and courthouses known collectively as Civic Center, Manhattan.