Flag on Prospect Hill debate

[12][note 3] Colonial propaganda generally made the distinction between the Crown, to which most colonists still remained loyal, and the parliament and the parliamentary executive, which was viewed as the cause of their grievances.

[19] Its use by the American revolutionaries was "in a sense a challenge to authority" as the concept of a national flag that represents both the government and the people is modern and did not prevail in the 18th century.

The authors and promoters of this deliberate conspiracy ... meant only to amuse by vague expressions of attachment to the Parent State, and the strongest protestations of loyalty to me, while they were preparing for a general revolt.

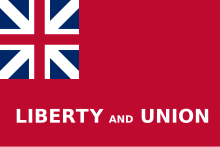

The design is nearly identical to the Flag of the British East India Company that was chartered in England in 1600 and played a pivotal role in the Boston Tea Party at the beginning of the American Revolution.

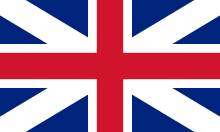

[7] George Washington's letter to his friend and aide-de-camp Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Reed, dated 4 January 1776, states that: ...we had hoisted the Union Flag in compliment to the United Colonies; but behold!

[...][27] There appears to be no reason arising from Washington's words or the context to doubt that he was referring to anything other than the British Union Flag and that what he was conveying to Reed "was the irony of the Army's hoisting a symbol of the Crown just before receiving the King's message of hostility toward the colonies".

[31] There is a third eyewitness account contained in a letter by British Lieutenant William Carter of the 40th Regiment of Foot dated 26 January 1776, which states: The King's speech was sent by a flag [of truce] to them on the 1st instant.

The first appeared on 15 January 1776 in Philadelphia's Dunlap's Pennsylvania Packet or the General Advertiser which states: Our advices conclude with the following anecdote:-That upon the King's Speech arriving in Boston, a great number of them were reprinted and sent out to our lines on the 2nd of January, which being also the day of forming the new army, the great Union Flag was hoisted on Prospect Hill, in compliment to the United Colonies.-this happening soon after the Speeches were delivered at Roxbury, but before they were received at Cambridge, the Boston gentry supposed it to be a token of the deep impression the Speech had made, and a signal of submission-That they were much disappointed at finding several days elapse without some formal measure leading to a surrender, with which they had begun to flatter themselves.

[33] There was another secondary account that appeared in the 1776 edition of the British publication The Annual Register that states: The arrival of a copy of the King's speech, with an account of the fate of the petition from the continental congress, is said to have excited the greatest degree of rage and indignation among them; as a proof of which, the former was publicly burnt in the camp; and they are said upon this occasion to have changed their colours, from a plain ground, which they had hitherto used, to a flag with thirteen stripes, as a symbol of the number and union of the colonies".

The plain ground changing to a field of thirteen stripes faithfully "recalls the transition from the British red ensign to the American Continental colors".

[33] Ansoff asserts the idea that the Continental Colours was raised on Prospect Hill had originated in a footnote in a history of the Siege of Boston published by Richard Frothingham in 1849.

The Annual Register (1776) says the Americans, so great was their rage and indignation, burnt the speech and "charged their colors from a plain red ground, which they had hitherto used, to a flag with thirteen stripes, as a symbol of the number and union of the colonies".

The term "great union" is found in a 1768 royal warrant concerning the colours carried by British infantry regiments and applies "generically to the design of the combined English and Scottish crosses, rather than to a particular flag".

[38] He stated that Preble evidently substitutes the word "grand" for "great" which appeared in the letter published in the Pennsylvania Gazette on 17 January 1776 and given his work is accepted as the seminal history of the American flag "his mistake has been perpetrated in vexillological and general literature ever since".

[38] However, in his response to Byron DeLear in 2015, Ansoff makes a correction that the first recorded use of the term "Grand Union" is actually by historian Thompson Westcott in 1852.

[40] Byron DeLear has argued in favour of the conventional history based on a review of "eighteenth-century linguistic standards, contextual historical trends, and additional primary and secondary sources".

[21] He argues that it was suitable for Washington and others to have referred to the Continental Colours in this way, given that "At the time of the introduction of the new striped union flag was the best abbreviated way to describe it".

[53] He notes that in seven of the eight examples given by DeLear, "the writer qualified his description to make it clear that he was not referring to a normal British union flag, but to an 'American' or 'Continental' version and/or one that contained stripes".

[62] In a message to Sir Grey Cooper dated 10 January 1776 a British spy in Philadelphia Gilbert Barkly, refers to the Continental Colours as being "what they call the Ammerican flag".

[63] DeLear states that at the very least "it is not too far of a stretch to presume-at the very least-that knowledge of that flag (and what it evidently represented) had passed from Philadelphia to Cambridge among principals of the American war effort".

[64] It was a stage in the American Revolution amid escalating British violence "with ships and stores seized, forts captured, and cities burned".

[65] DeLear argues that "notions of nationhood were clearly maturing in this exact time and space" and notes the earliest surviving documentary evidence of the term "United States of America" was written at Washington's headquarters just after the New Year's Day flag raising ceremony.

DeLear compares the "relatively ad hoc manner" of such displays, as cited by Ansoff, with the ceremonies when the Continental Colours debuted aboard the Alfred or the flag-raising on Prospect Hill.

[72] Reed is the author of one of the few known flag directives of the period in a message to Colonel John Glover and Stephen Moylan dated 20 October 1775.

Marshall eventually discovered that "swaths of Washington's diary were missing, especially sections during the war and presidency, and that a handful of key letters has also vanished".

DeLear speculates that among "the twelve missing Reed letters from November to December 1775" and other items from Washington's archives that "may have been suppressed" there could "very plausibly" have been more information about the origin and proclamation of the Continental Colours.

[53] DeLear concludes that in addition to all modern accounts of the event on Prospect Hill that have the Continental Colours flying there, all secondary sources "report the same conventional history, and, if erroneous, nowhere were they later corrected until Ansoff".