Flaying of Marsyas (Titian)

It is one of several canvases with mythological subjects from Ovid which Titian executed in his late years, mostly the poesie series for King Philip II of Spain, of which this painting seems not to have been part.

[6] Beginning an extended analysis, Sir Lawrence Gowing wrote that "All these months – it is not too much to say – London has been half under the spell of this masterpiece, in which the tragic sense that overtook Titian’s poesie in his seventies reached its cruel and solemn extreme.

"[7] The choice of such a violent scene was perhaps inspired by the death of Marcantonio Bragadin, the Venetian commander of Famagusta in Cyprus who was flayed by the Ottomans when the city fell in August 1571, causing enormous outrage in Venice.

[9] Both artists follow the account in Ovid's Metamorphoses (Book 6, lines 382–400),[10] which covers the contest very quickly, but describes the flaying scene at relative length, though with few indications that would help to visualize it.

[12] Marsyas was a skillful player of the classical aulos or double flute, for which by Titian's time pan pipes were usually substituted in art,[13] and his set hangs from the tree over his head.

An idea of the contest reinforcing the general moral and artistic superiority of the courtly lyre, or modern stringed instruments, over the rustic and frivolous wind family was present in much ancient discussion, and perhaps retained some relevance in the 16th century.

The boy or young satyr is looking rather vacuously out at the viewer, those in their prime are concentrating on their tasks with a variety of expressions, and Midas contemplates the scene, apparently with melancholy resignation, but making no further attempt to intervene.

[37] It is unknown whether the painting had an intended recipient; Titian's main client in his last years was King Philip II of Spain, but the picture is not mentioned in the surviving correspondence.

[43] He was the nephew of (Edvard, Everard or) Everhard Jabach, a banker from Cologne who was one of the greatest private collectors of the century, and also acted as an agent for Cardinal Mazarin and Louis XIV of France.

In the 1650s the superb collection of Arundel's friend Charles I of England was being dispersed in London, and Jabach, acting on behalf of Louis, was one of many international buyers active, with agents on the ground.

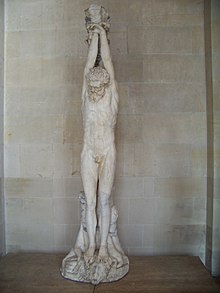

[52] Marsyas, as a single figure, was a well-known subject in Roman and Hellenistic sculpture, with a famous type showing him tied and hanging with his arms above his head.

[55] Much closer is "an awkward sketch for a now damaged fresco" by Giulio Romano in the Palazzo Te in Mantua (1524–34),[56] for which there is also a drawing in the Louvre; this is clearly the main source for the composition.

[57] The seated figure of Midas has donkey ears, and is more clearly distressed, holding his hands over his face, and Apollo, bending down rather than on one knee, is not cutting, but is pulling the skin off like a jacket.

[58] Andrea Schiavone's Judgement of Midas in the British Royal Collection (in 2017 displayed in the Gallery at Kensington Palace), is some twenty years earlier, from c. 1548–50, and is comparable to Titian, in atmosphere and some details of the composition.

Titian "must also have remembered elements of this painting: the pensive and abstracted attitudes of Apollo and Midas, and the radically free impressionistic brushwork used to heighten the dramatic mood of the story."

[59] Midas or "Midas/Titian adopts the traditional melancholic's pose", which Titian would have known from Raphael's supposed portrait of Michelangelo as Heraclitus in The School of Athens, and Albrecht Dürer's Melencolia I, not to mention the Schiavone.

... one can still see passages of smoky preliminary painting (notably the ghostly body of Apollo) but the blood, dogs' tongues and the ribbons in the trees are brilliant red.

"[66] For John Steer "it is not individual colours that tell, but an all-over emanation of broken touches, evoking a greenish-gold, that is splattered, appropriately to the theme, with reds like splotches of blood.