Floridan aquifer

The Floridan aquifer system is the primary source of drinking water for most cities in central and northern Florida as well as eastern and southern Georgia, including Brunswick, Savannah, and Valdosta.

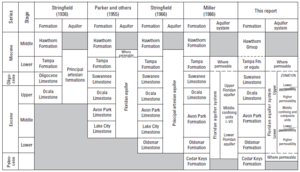

Stringfield first identified the existence of the Floridan Aquifer in peninsular Florida and referred to the carbonate units as the "principal artesian formations.

Industrial supply for pulp and paper mills became a large proportion of the water withdrawn starting in the late 1930s.

[1] The Upper Floridan aquifer contains freshwater over much of its extent, though is brackish and saline south of Lake Okeechobee.

[2] The Floridan aquifer system crops out in central and southern Georgia where the limestone, and its weathered byproducts, are present at land surface.

The aquifer system generally dips below the land surface to the south where it becomes buried beneath surficial sand deposits and clay.

In areas depicted in brown in the image at the right, the Floridan aquifer system crops out and is again exposed at land surface.

These regions are particularly prone to sinkhole activity due to the proximity of the karstified limestone aquifer to land surface.

Low permeability limestone rocks of Paleocene age (e.g. Cedar Keys Formation) form the base of the Floridan aquifer system.

[10][19] Where the Floridan aquifer system is at or near land surface (areas shaded brown in image above), clays are thin or absent and dissolution of the limestone is intensified and many springs and sinkholes are apparent.

Transmissivity of the aquifer in karstified areas such as these is much higher owing to the development of large, well-connected conduits within the rock (see image at right).

A record peak flow from the spring on April 11, 1973, was measured at 14,324 US gallons (54.22 m3) per second – equal to 1.24 billion US gal (4.68 million m3; 3,800 acre⋅ft) per day.

Where these intervening sediments and rock are permeable, the Upper and Lower Floridan aquifers behave as a single unit.

In the panhandle of Florida and southwest Alabama, the base is coincident with the top of the Bucatunna Clay Confining Unit.

[10] The carbonate rocks that compose the Floridan aquifer system have highly variable hydraulic properties, including porosity and permeability.

[22] Where the aquifer is unconfined or thinly confined, infiltrating water dissolves the rock and transmissivity tends to be relatively high.

Formation of sinkholes can be accelerated by intense withdrawals of groundwater over short periods of time, such as those caused by pumping for frost-protection of winter crops in west-central Florida.

[23][27][28] Sinkholes that developed beneath gypsum stacks in 1994[29] and 2016[30] caused a loss of millions of gallons mineralized water containing phosphogypsum and phosphoric acid, by-products of the production of fertilizer from phosphate rock.