Flux

Flux describes any effect that appears to pass or travel (whether it actually moves or not) through a surface or substance.

Flux is a concept in applied mathematics and vector calculus which has many applications in physics.

For transport phenomena, flux is a vector quantity, describing the magnitude and direction of the flow of a substance or property.

[2] As fluxion, this term was introduced into differential calculus by Isaac Newton.

[3] His seminal treatise Théorie analytique de la chaleur (The Analytical Theory of Heat),[4] defines fluxion as a central quantity and proceeds to derive the now well-known expressions of flux in terms of temperature differences across a slab, and then more generally in terms of temperature gradients or differentials of temperature, across other geometries.

The result of this operation is called the surface integral of the flux.

In transport phenomena (heat transfer, mass transfer and fluid dynamics), flux is defined as the rate of flow of a property per unit area, which has the dimensions [quantity]·[time]−1·[area]−1.

For example, the amount of water that flows through a cross section of a river each second divided by the area of that cross section, or the amount of sunlight energy that lands on a patch of ground each second divided by the area of the patch, are kinds of flux.

In all cases the frequent symbol j, (or J) is used for flux, q for the physical quantity that flows, t for time, and A for area.

In this case the surface in which flux is being measured is fixed and has area A.

), and measures the flow through the disk of area A perpendicular to that unit vector.

The unit vector thus uniquely maximizes the function when it points in the "true direction" of the flow.

For example, the arg max construction is artificial from the perspective of empirical measurements, when with a weathervane or similar one can easily deduce the direction of flux at a point.

Rather than defining the vector flux directly, it is often more intuitive to state some properties about it.

Also, one can take the divergence of any of these fluxes to determine the accumulation rate of the quantity in a control volume around a given point in space.

As mentioned above, chemical molar flux of a component A in an isothermal, isobaric system is defined in Fick's law of diffusion as:

[5] For dilute gases, kinetic molecular theory relates the diffusion coefficient D to the particle density n = N/V, the molecular mass m, the collision cross section

In turbulent flows, the transport by eddy motion can be expressed as a grossly increased diffusion coefficient.

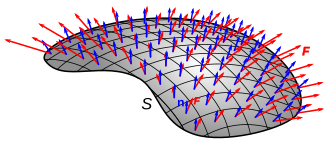

[11] As a mathematical concept, flux is represented by the surface integral of a vector field,[12]

See also the image at right: the number of red arrows passing through a unit area is the flux density, the curve encircling the red arrows denotes the boundary of the surface, and the orientation of the arrows with respect to the surface denotes the sign of the inner product of the vector field with the surface normals.

An electric "charge", such as a single proton in space, has a magnitude defined in coulombs.

In pictorial form, the electric field from a positive point charge can be visualized as a dot radiating electric field lines (sometimes also called "lines of force").

Conceptually, electric flux can be thought of as "the number of field lines" passing through a given area.

Hence, units of electric flux are, in the MKS system, newtons per coulomb times meters squared, or N m2/C.

If one considers the flux of the electric field vector, E, for a tube near a point charge in the field of the charge but not containing it with sides formed by lines tangent to the field, the flux for the sides is zero and there is an equal and opposite flux at both ends of the tube.

This is a consequence of Gauss's Law applied to an inverse square field.

[15] In free space the electric displacement is given by the constitutive relation D = ε0 E, so for any bounding surface the D-field flux equals the charge QA within it.

where dℓ is an infinitesimal vector line element of the closed curve

, with magnitude equal to the length of the infinitesimal line element, and direction given by the tangent to the curve

The direction is such that if current is allowed to pass through the wire, the electromotive force will cause a current which "opposes" the change in magnetic field by itself producing a magnetic field opposite to the change.

Top: Three field lines through a plane surface, one normal to the surface, one parallel, and one intermediate.

Bottom: Field line through a curved surface , showing the setup of the unit normal and surface element to calculate flux.