Poynting vector

[2] Oliver Heaviside also discovered it independently in the more general form that recognises the freedom of adding the curl of an arbitrary vector field to the definition.

This frequent condition holds in the following simple example in which the Poynting vector is calculated and seen to be consistent with the usual computation of power in an electric circuit.

Although problems in electromagnetics with arbitrary geometries are notoriously difficult to solve, we can find a relatively simple solution in the case of power transmission through a section of coaxial cable analyzed in cylindrical coordinates as depicted in the accompanying diagram.

The model (and solution) can be considered simply as a DC circuit with no time dependence, but the following solution applies equally well to the transmission of radio frequency power, as long as we are considering an instant of time (during which the voltage and current don't change), and over a sufficiently short segment of cable (much smaller than a wavelength, so that these quantities are not dependent on Z).

The center conductor is held at voltage V and draws a current I toward the right, so we expect a total power flow of P = V · I according to basic laws of electricity.

By evaluating the Poynting vector, however, we are able to identify the profile of power flow in terms of the electric and magnetic fields inside the coaxial cable.

) symmetry dictates that they are strictly in the radial direction and it can be shown (using Gauss's law) that they must obey the following form:

It is also possible to combine the electric displacement field D with the magnetic flux B to get the Minkowski form of the Poynting vector, or use D and H to construct yet another version.

The Umov–Poynting vector[11] discovered by Nikolay Umov in 1874 describes energy flux in liquid and elastic media in a completely generalized view.

where Here ε and μ are scalar, real-valued constants independent of position, direction, and frequency.

In principle, this limits Poynting's theorem in this form to fields in vacuum and nondispersive[clarification needed] linear materials.

In the important case that E(t) is sinusoidally varying at some frequency with peak amplitude Epeak, Erms is

This is the most common form for the energy flux of a plane wave, since sinusoidal field amplitudes are most often expressed in terms of their peak values, and complicated problems are typically solved considering only one frequency at a time.

The "microscopic" (differential) version of Maxwell's equations admits only the fundamental fields E and B, without a built-in model of material media.

It can be derived directly from Maxwell's equations in terms of total charge and current and the Lorentz force law only.

[15] Since only the microscopic fields E and B occur in the derivation of S = (1/μ0) E × B and the energy density, assumptions about any material present are avoided.

The Poynting vector and theorem and expression for energy density are universally valid in vacuum and all materials.

More commonly, problems in electromagnetics are solved in terms of sinusoidally varying fields at a specified frequency.

The results can then be applied more generally, for instance, by representing incoherent radiation as a superposition of such waves at different frequencies and with fluctuating amplitudes.

The time-averaged power flow (according to the instantaneous Poynting vector averaged over a full cycle, for instance) is then given by the real part of Sm.

The imaginary part is usually ignored, however, it signifies "reactive power" such as the interference due to a standing wave or the near field of an antenna.

Multiplication by 1/2 is required to properly describe the power flow since the magnitudes of Em and Hm refer to the peak fields of the oscillating quantities.

If rather the fields are described in terms of their root mean square (RMS) values (which are each smaller by the factor

[18]: 454 The density of the linear momentum of the electromagnetic field is S/c2 where S is the magnitude of the Poynting vector and c is the speed of light in free space.

[12]: 258–260, 605–612 The following section gives an example which illustrates why it is not acceptable to add an arbitrary solenoidal field to E × H. The consideration of the Poynting vector in static fields shows the relativistic nature of the Maxwell equations and allows a better understanding of the magnetic component of the Lorentz force, q(v × B).

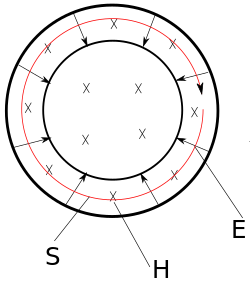

To illustrate, the accompanying picture is considered, which describes the Poynting vector in a cylindrical capacitor, which is located in an H field (pointing into the page) generated by a permanent magnet.

Although there are only static electric and magnetic fields, the calculation of the Poynting vector produces a clockwise circular flow of electromagnetic energy, with no beginning or end.

While the circulating energy flow may seem unphysical, its existence is necessary to maintain conservation of angular momentum.

The momentum of an electromagnetic wave in free space is equal to its power divided by c, the speed of light.

[19] If one were to connect a wire between the two plates of the charged capacitor, then there would be a Lorentz force on that wire while the capacitor is discharging due to the discharge current and the crossed magnetic field; that force would be circumferential to the central axis and thus add angular momentum to the system.