Focus (linguistics)

In linguistics, focus (abbreviated FOC) is a grammatical category that conveys which part of the sentence contributes new, non-derivable, or contrastive information.

Research on focus spans numerous subfields including phonetics, syntax, semantics, pragmatics, and sociolinguistics.

Focus has also been linked to other more general cognitive processes, including attention orientation.

[5][6] In such approaches, contrastive focus is understood as the coding of information that is contrary to the presuppositions of the interlocutor.

Standard formalist approaches to grammar argue that phonology and semantics cannot exchange information directly (See Fig.

Historically, generative proposals made focus a feature bound to a single word within a sentence.

Focus was later suggested to be a structural position at the beginning of the sentence (or on the left periphery) in Romance languages such as Italian, as the lexical head of a Focus Phrase (or FP, following the X-bar theory of phrase structure).

Jackendoff,[18] Selkirk,[13][14] Rooth,[19][20] Krifka,[21] Schwarzschild[15] argue that focus consists of a feature that is assigned to a node in the syntactic representation of a sentence.

Because focus is now widely seen as corresponding between heavy stress, or nuclear pitch accent, this feature is often associated with the phonologically prominent element(s) of a sentence.

Sound structure (phonological and phonetic) studies of focus are not as numerous, as relational language phenomena tend to be of greater interest to syntacticians and semanticists.

Rooth,[19] Jacobs,[22] Krifka,[21] and von Stechow[23] claim that there are lexical items and construction specific-rules that refer directly to the notion of focus.

Dryer,[24] Kadmon,[25] Marti,[26] Roberts,[16] Schwarzschild,[27] Vallduvi,[28] and Williams[29] argue for accounts in which general principles of discourse explain focus sensitivity.

Different ways of pronouncing the sentence affects the meaning, or, what the speaker intends to convey.

The class of focus sensitive expressions in which focus can be associated with includes exclusives (only, just) non-scalar additives (merely, too) scalar additives (also, even), particularlizers (in particular, for example), intensifiers, quantificational adverbs, quantificational determiners, sentential connectives, emotives, counterfactuals, superlatives, negation and generics.

In the alternative semantics approach to focus pioneered by Mats Rooth, each constituent

For a sentence such as (9), the ordinary denotation will be the proposition which is true iff Mary likes Sue.

Focused constituents denote the set of all (contextually relevant) semantic objects of the same type.

In alternative semantics, the primary composition rule is Pointwise Functional Application.

Applying this rule to example (9) would give the following focus denotation if the only contextually relevant individuals are Sue, Bill, Lisa, and Mary The focus denotation can be "caught" by focus-sensitive expressions like "only" as well as other covert items such as the squiggle operator.

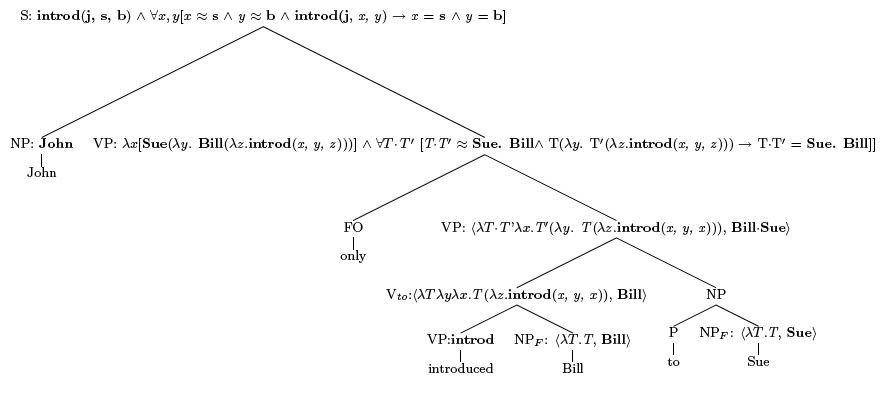

Krifka claims focus partitions the semantics into a background part and focus part, represented by the pair: The logical form of which represented in lambda calculus is: This pair is referred to as a structured meaning.

Structured meanings allow for a compositional semantic approach to sentences that involve single or multiple foci.

To see Krifka’s approach illustrated, consider the following examples of single focus shown in (10) and multiple foci shown in (11): Generally, the meaning of (10) can be summarized as John introduced Bill to Sue and no one else, and the meaning of (11) can be summarized as the only pair of persons such that John introduced the first to the second is Bill and Sue.

To illustrate this point, consider the following discourse in (12) and (13): In (13) we note that the verb make is not given by the sentence in (12).

[33] The percolation of F-markings in a syntactic tree is sensitive to argument structure and head-phrase relations.

Rule (15b) allows F-marking to project from the direct object to the head verb adopted.

[33] Schwarzschild[15] points out weaknesses in Selkirk’s[13][14] ability to predict accent placement based on facts about the discourse.

-type-shifting "is a way of transforming syntactic constituents into full propositions so that it is possible to check whether they are entailed by the context".

[33] Recent empirical work by German et al.[33] suggests that both Selkirk’s[13][14] and Schwarzschild’s[15] theory of accentuation and F-marking makes incorrect predictions.

German et al. argue for a stochastic constraint-based grammar similar to Anttila[35] and Boersma[36] that more fluidly accounts for how speakers accent words in discourse.