Folha de S.Paulo

The newspaper is the centerpiece for Grupo Folha, a conglomerate that also controls UOL (Universo Online), the leading Internet portal in Brazil; polling institute Datafolha; publishing house Publifolha; book imprint Três Estrelas; printing company Plural; and, in a joint-venture with the Globo group, the business daily Valor, among other enterprises.

It was an evening newspaper, with a project that privileged shorter, clearer articles, focusing more on news than on opinion, and a positioning closer to the themes that affected the daily life of the paulistanos (São Paulo city dwellers), particularly the working classes.

The paper was competing against O Estado de S. Paulo the leading newspaper in the city, which represented rural moneyed interests and took on a conservative, traditional and rigid posture; Folha was always more responsive to societal needs.

[6] Business flourished, and the controlling partners decided to buy a building to serve as headquarters, a printing press and then, in 1925, to create a second newspaper, Folha da Manhã.

Juca Pato was supposed to represent the Average Joe, and served as a vehicle for ironic criticism of political and economic problems, always repeating the tagline "it could have been worse".

However, in 1929, Olival Costa, by then sole proprietor of the Folhas, mended his fences with the São Paulo Republicans, and broke his links to opposition groups connected to Getúlio Vargas and his Aliança Liberal.

[7] Folha's premises were destroyed, and Costa sold the company to Octaviano Alves de Lima, a businessman whose main activity was coffee production and trade.

Matarazzo financed the purchase of new, modern printing presses and saw the investment as a way to respond to the attacks he suffered from newspapers owned by his business rival Assis Chateaubriand.

Nabantino Ramos balanced those losses against the Count's initial financing and, some months later, declared that the company's debt to Matarazzo was fully paid and took over editorial control of the papers.

[7] Nabantino Ramos, who was an attorney, was very interested in modern managerial techniques, and during the 1940s and 1950s adopted several innovations: competitive examinations for new hires, journalism courses, performance bonuses, fact checking.

In 1949, Ramos started a third newspaper, Folha da Tarde, and sponsored dozens of civic campaigns against corruption and organized crime, for the defense of water sources, infrastructure improvements, city works, and plenty more.

Frias chose scientist José Reis, one of the leading lights in the Brazilian Association for the Advancement of Science (SBPC), as newsroom head, and also hired Cláudio Abramo, the journalist credited with the successful updating of rival "O Estado de S. Paulo".

After the financial and business hardships were left behind, the new management started to concentrate on industrial modernization and in creating a distribution network that would facilitate the circulation leaps that would follow.

Later that same year, Cláudio Abramo lost his position as newsroom head, and Folha would only claim back a more avowedly political stance, instead of the uncritical "neutrality" adopted when editorials were suspended, late in 1973.

[10] More innovative than its competitor, Folha started to gain hold of the middle classes that were growing under the Brazilian "economic miracle", and became the newspaper of choice for young people and women.

A series of documents circulated periodically, defining the newspaper's editorial project as part of the so-called Projeto Folha, implemented in the newsroom under the supervision of Carlos Eduardo Lins da Silva and Caio Túlio Costa.

At the same time, checks and balances were instituted through internal controls: the Manual, the daily "Corrections" section adopted in 1991, a rule stating that objections to any article expressed by readers or for people mentioned in the news should be published, and, above all, the ombudsman position created in 1989; this position entails job security for its holder, whose aim is to criticize Folha and deal with complaints by readers and people mentioned in the news.

From the midpoint of the Brazilian military rule, Folha kept a critical stance towards several succeeding administrations (Ernesto Geisel, João Figueiredo, José Sarney, Fernando Collor, Itamar Franco).

The newspaper's coverage about the administrations of Fernando Henrique Cardoso (PSDB) and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT) led to accusations of anti-governmental bias in both cases, though the two Presidents belong to rival parties.

The newspaper answered by defining the professors' indignation as "cynical and untrue", and claiming that both of them were well-respected figures and did not express similar disdain regarding left-wing dictatorships such as Cuba's.

[13] The use of the word "ditabranda" led to Folha being the target of criticism on Internet discussion boards and other media vehicles, particularly those closer to left-wing thinking, such as the magazines Fórum,[14] Caros Amigos (that ran a cover story about the case)[15] and Carta Capital.

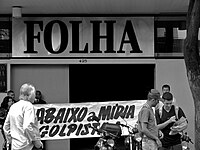

[16] On 7 March, there was a protest in front of Folha's headquarters, in Central São Paulo, against the use of the word "ditabranda" and to express solidarity to Maria Victoria Benevides e Fábio Konder Comparato, who did not take part in the act.

[19] On 5 April 2009, Folha ran an article about a supposed plan by guerrilla group Vanguarda Armada Revolucionária Palmares to kidnap Antonio Delfim Netto, who was the Finance minister during the military rule, in the early 1970s, and alongside printed a criminal file about Dilma Rousseff, who was already the Brazilian President.

Ombudsman Carlos Eduardo Lins da Silva wrote about the case stating, in his Folha column, that "after the Minister contested the authenticity of the police record, the newspaper admitted to not having verified its accuracy.

I found insufficient the justifications offered to explain this error, and suggested that an independent panel should be empowered to find out what happened and recommend new procedures to avoid any repetition.

[22] The police record is available on the Website of the radical Ternuma group and is not included in the São Paulo State Archives, that hold all files pertaining to the former Department for Social and Political Order.

[28][29] On 29 June 2010, Folha mistakenly published an ad by Extra Hipermercados (owned by Grupo Pão de Açúcar, one of the sponsors of the Brazil national football team), which read: "A I qembu le sizwe sai do Mundial.

[33] Those surveys notwithstanding, Folha was criticized for its "false impartiality" by website Falha de S. Paulo, created to spoof the newspaper for its supposedly biased coverage that favored José Serra and opposed the Lula administration.

Folha went to court appealing for closure of the Website, claiming that its usage of a logo identical to the newspaper's, with the change of just one letter in the name, was not only confusing readers but also represented a trademark violation.

[35] However, the judge in charge of the case claimed that his decision was not due to "the satirical aspect, which our current laws would allow, but to the use of a brand extremely similar to the plaintiff's (Folha)", thus accepting the newspaper's argument.