Folk art

The art form is categorised as "divergent... of cultural production ... comprehended by its usage in Europe, where the term originated, and in the United States, where it developed for the most part along very different lines.

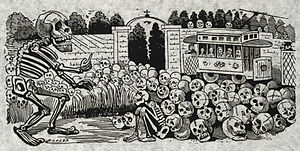

"[2] From a European perspective, Edward Lucie-Smith described it as "Unsophisticated art, both fine and applied, which is supposedly rooted in the collective awareness of simple people.

The folk art has a recognizable style and method in crafting its pieces, which allows products to be recognized and attributed to a single individual or workshop.

To be sure, the artist may have been obliged by group expectations to work within the norms of transmitted forms and conventions, but individual creativity – which implied personal aesthetic choices and technical virtuosity – saved received or inherited traditions from stagnating and permitted them to be renewed in each generation.

Folk objects imply a mode of production common to preindustrial communal society where knowledge and skills were personal and traditional.

Instead, "the concept of group art implies, indeed requires, that artists acquire their abilities, both manual and intellectual, at least in part from communication with others.

Teaching of the craft through informal means outside of institutions has opened the genre to artists who may face barrier to entry in other disciplines.

Canadian folk artist Maud Lewis, for example, suffered from an undiagnosed congenital illness, making formal art schooling a challenge.

[9] Despite barriers to formal education, Lewis became one of Canada's most famous folk artists, creating thousands of paintings of life in Nova Scotia.

Examples are Leon "Peck" Clark, a Mississippi basket maker, who learned his skills from a community member; George Lopez of Cordova, New Mexico, who is a sixth-generation santos carver whose children also carve; and the Yorok-Karok basket weavers, who explain that relatives generally taught them to weave.” [11] The known type of the object must be, or have originally been, utilitarian; it was created to serve some function in the daily life of the household or the community.

However, since the form itself was a distinct type with its function and purpose, folk art has continued to be copied over time by different individuals.

An object can be created to match the community's expectations, and the artist may design the product with unspoken cultural biases to reflect this aim.

The list below includes a sampling of different materials, forms, and artisans involved in the production of everyday and folk art objects.

[2] Many of these groupings and individual objects might also resemble "folk art" in its aspects, however may not align to the defining characteristics outlined above.

[18] In 1951, artist, writer and curator Barbara Jones organised the exhibition Black Eyes and Lemonade at the Whitechapel Gallery in London as part of the Festival of Britain.

[19] The United Nations recognizes and supports cultural heritage around the world,[20] in particular UNESCO in partnership with the International Organization of Folk Art (IOV).

The NEA guidelines define as criteria for this award a display of "authenticity, excellence, and significance within a particular tradition" for the artists selected.