Food history

In 2020, archeological research discovered a frescoed thermopolium (a fast-food counter) in an exceptional state of preservation from 79 CE/AD in Pompeii, including 2,000-year-old foods available in some of the deep terra cotta jars.

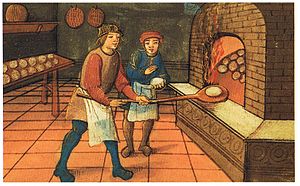

[5] During classical antiquity, diets consisted of simple fresh or preserved whole foods that were either locally grown or transported from neighboring areas during times of crisis.

The most prevalent butcher's meats were pork, chicken, and other domestic fowl; beef, which required greater investment in land, was less common.

Cod and herring were mainstays among the northern populations; dried, cooked or salted, they made their way far inland, but a wide variety of other saltwater and freshwater fish was also eaten.

Poor families primarily consumed grains and vegetables in the form of stew, soup, or pottage, and anything grown on their own small plots of land.

Smaller portion sizes developed around this time due to various cultural influences, and these large, table-long meals were essentially picked at by the nobility.

The Middle Ages diet of the upper class and nobility included manchet bread, a variety of meats like venison, pork, and lamb, fish and shellfish, spices, cheese, fruits, and a limited number of vegetables.

As time went by and living standards improved, even lower class people, particularly those in urban centers, could enjoy the taste of foreign spices like pepper, nutmeg and cinnamon.

The church calendar included many fasts spread throughout the year; the longest of these was Lent, the late winter weeks preceding Easter.

The pork was pickled in wine or vinegar with garlic (carne de vinha d'alhos) tied to Portuguese cuisine that later became vindaloo.

After 1700, innovative farmers experimented with new techniques to increase yield and looked into new products such as hops, rapeseed oil, artificial grasses, vegetables, fruit, dairy foods, commercial poultry, rabbits, and freshwater fish.

[17][page needed] Labourers in Western Europe in the 18th century ate bread and gruel, often in a soup with greens and lentils, a little bacon, and occasionally potato or a bit of cheese.

[19] In the immigrant neighbourhoods of fast-growing American industrial cities, housewives purchased ready-made food through street peddlers, hucksters, push carts, and small shops operated from private homes.

[20] In the first half of the 20th century there were two world wars, which in many places resulted in rationing and hunger; sometimes the starvation of the civilian populations was used as a powerful new weapon.

[21] In Germany during World War I, the rationing system in urban areas virtually collapsed, with people eating animal fodder to survive the Turnip Winter.

Meat production was stretched to the limit in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and Argentina, with oceanic shipping closely controlled by the British.

Now instead of an experienced cook spending hours on difficult custards and puddings, the housewife could purchase instant foods in jars, or powders that could be quickly mixed.

As part of the Marshall Plan in 1948–1950, the United States provided technological expertise and financing for high-productivity large-scale agribusiness operations in postwar Europe.

Poultry was a favorite choice, with the rapid expansion in production, a sharp fall in prices, and widespread acceptance of the many ways to serve chicken.

[35] However, lack of genetic diversity, due to the very limited number of varieties initially introduced, left the crop vulnerable to disease.

In 1845, a plant disease known as late blight, caused by the fungus-like oomycete Phytophthora infestans, spread rapidly through the poorer communities of western Ireland as well as parts of the Scottish Highlands, resulting in the crop failures that led to the Great Irish Famine.

[36] Currently China is the largest potato producing country followed by India as of 2017, FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Where rice originated has always been a hot point of debate between India and China, as both countries started cultivating it around the same time (according to numerous history books and records).

The Jesuits were leading producers of chocolate, obtaining it from the Amazon jungle and Guatemala and shipping it across the world to Southeast Asia, Spain and Italy.

Fermented cocoa beans had to be ground on heated grindstones to prevent producing oily chocolate: a process that was foreign to many Europeans.

As a beverage, chocolate remained largely within the Catholic world as it was not considered a food by the church[clarification needed] and thus could be enjoyed during fasting.

The Jesuits introduced several foods and cooking techniques to Japan: deep frying (tempura), cakes and confectionery (kasutera, confetti), as well as the bread still called by the Iberian name pan.