Kitchen utensil

However, they are also comparatively heavier than utensils made of other materials, require scrupulous cleaning to remove poisonous tarnish compounds, and are not suitable for acidic foods.

Cast iron kitchen utensils are less prone to rust by avoiding abrasive scouring and extended soaking in water in order to build up its layer of seasoning.

In particular, iron egg-beaters or ice cream freezers are tricky to dry, and the consequent rust if left wet will roughen them and possibly clog them completely.

When storing iron utensils for long periods, van Rensselaer recommended coating them in non-salted (since salt is also an ionic compound) fat or paraffin.

[7] Iron utensils have little problem with high cooking temperatures, are simple to clean as they become smooth with long use, are durable and comparatively strong (i.e. not as prone to breaking as, say, earthenware), and hold heat well.

Stainless steel is considerably less likely to rust in contact with water or food products, and so reduces the effort required to maintain utensils in clean useful condition.

Thompson noted that as a consequence of this the use of such glazed earthenware was prohibited by law in some countries from use in cooking, or even from use for storing acidic foods.

[11] Aluminium's advantages over other materials for kitchen utensils is its good thermal conductivity (which is approximately an order of magnitude greater than that of steel), the fact that it is largely non-reactive with foodstuffs at low and high temperatures, its low toxicity, and the fact that its corrosion products are white and so (unlike the dark corrosion products of, say, iron) do not discolour food that they happen to be mixed into during cooking.

[4] However, its disadvantages are that it is easily discoloured, can be dissolved by acidic foods (to a comparatively small extent), and reacts to alkaline soaps if they are used for cleaning a utensil.

"Of the culinary utensils of the ancients", wrote Mrs Beeton, "our knowledge is very limited; but as the art of living, in every civilized country, is pretty much the same, the instruments for cooking must, in a great degree, bear a striking resemblance to one another".

For example: In the Middle Eastern villages and towns of the middle first millennium AD, historical and archaeological sources record that Jewish households generally had stone measuring cups, a meyḥam (a wide-necked vessel for heating water), a kederah (an unlidded pot-bellied cooking pot), a ilpas (a lidded stewpot/casserole pot type of vessel used for stewing and steaming), yorah and kumkum (pots for heating water), two types of teganon (frying pan) for deep and shallow frying, an iskutla (a glass serving platter), a tamḥui (ceramic serving bowl), a keara (a bowl for bread), a kiton (a canteen of cold water used to dilute wine), and a lagin (a wine decanter).

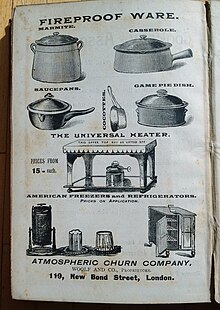

By 1858, Elizabeth H. Putnam, in Mrs Putnam's Receipt Book and Young Housekeeper's Assistant, wrote with the assumption that her readers would have the "usual quantity of utensils", to which she added a list of necessary items:[18] Copper saucepans, well lined, with covers, from three to six different sizes; a flat-bottomed soup-pot; an upright gridiron; sheet-iron breadpans instead of tin; a griddle; a tin kitchen; Hector's double boiler; a tin coffee-pot for boiling coffee, or a filter — either being equally good; a tin canister to keep roasted and ground coffee in; a canister for tea; a covered tin box for bread; one likewise for cake, or a drawer in your store-closet, lined with zinc or tin; a bread-knife; a board to cut bread upon; a covered jar for pieces of bread, and one for fine crumbs; a knife-tray; a spoon-tray; — the yellow ware is much the stringest, or tin pans of different sizes are economical; — a stout tin pan for mixing bread; a large earthen bowl for beating cake; a stone jug for yeast; a stone jar for soup stock; a meat-saw; a cleaver; iron and wooden spoons; a wire sieve for sifting flour and meal; a small hair sieve; a bread-board; a meat-board; a lignum vitae mortar, and rolling-pin, &c. — Putnam 1858, p. 318[19] Mrs Beeton, in her Book of Household Management, wrote: The following list, supplied by Messrs Richard & John Slack, 336, Strand, will show the articles required for the kitchen of a family in the middle class of life, although it does not contain all the things that may be deemed necessary for some families, and may contain more than are required for others.

As Messrs Slack themselves, however, publish a useful illustrated catalogue, which may be had at their establishment gratis, and which it will be found advantageous to consult by those about to furnish, it supersedes the necessity of our enlarging that which we give: — Isabella Mary Beeton, The Book of Household Management[20] Parloa, in her 1880 cookbook, took two pages to list all of the essential kitchen utensils for a well-furnished kitchen, a list running to 93 distinct sorts of item.

Breazeale advocated simplicity over dishwashing machines "that would have done credit to a moderate sized hotel", and noted that the most useful kitchen utensils were "the simple little inexpensive conveniences that work themselves into every day use", giving examples, of utensils that were simple and cheap but indispensable once obtained and used, of a stiff brush for cleaning saucepans, a sink strainer to prevent drains from clogging, and an ordinary wooden spoon.

While the advent of mass-produced standardized measuring instruments permitted even householders with little to no cooking skills to follow recipes and end up with the desired result and the advent of many utensils enabled "modern" cooking, on a stove or range rather than at floor level with a hearth, they also operated to raise expectations of what families would eat.

The labour-saving effect of the tools was cancelled out by the increased labour required for what came to be expected as the culinary norm in the average household.

– Pastry blender and potato masher

– Spatula and (hidden) serving fork

– Skimmer and chef's knife (small cleaver)

– Whisk and slotted spoon

– Spaghetti ladle

– Sieve and measuring spoon set

– Bottle brush and (spoon)