Obstetrical forceps

Common complications include the possibility of bruising the baby and causing more severe vaginal tears (perineal laceration) than would otherwise be the case.

Severe and rare complications (occurring less frequently than 1 in 200) include nerve damage, Descemet's membrane rupture,[2] skull fractures, and cervical cord injury.

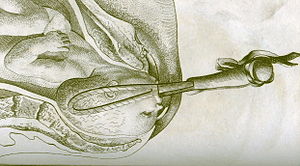

Forceps with a fixed lock mechanism are used for deliveries where little or no rotation is required, as when the fetal head is in line with the mother's pelvis.

[medical citation needed] The blade of each forceps branch is the curved portion that is used to grasp the fetal head.

The pelvic curve is shaped to conform to the birth canal and helps direct the force of the traction under the pubic bone.

Short forceps are applied on the fetal head already descended significantly in the maternal pelvis (i.e., proximal to the vagina).

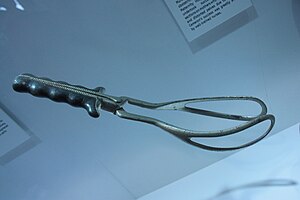

[medical citation needed] Kielland forceps (1915, Norwegian) are distinguished by having no angle between the shanks and the blades and a sliding lock.

The common misperception that there is no pelvic curve has become so entrenched in the obstetric literature that it may never be able to be overcome, but it can be proved by holding a blade of Kielland's against any other forceps of one's choice.

[6] Wrigley's forceps were designed for use by general practitioner obstetricians, having the safety feature of an inability to reach high into the pelvis.

A regional anaesthetic (usually either a spinal, epidural or pudendal block) is used to help the mother remain comfortable during the birth.

[8][page needed] The accepted clinical standard classification system for forceps deliveries according to station and rotation was developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and consists of:[medical citation needed] The obstetric forceps were invented by the eldest son of the Chamberlen family of surgeons.

The Chamberlens were French Huguenots from Normandy who worked in Paris before they migrated to England in 1569 to escape the religious violence in France.

The success of this dynasty of obstetricians with the royal family and high nobles was related in part to the use of this "secret" instrument allowing delivery of a live child in difficult cases.

In fact, the instrument was kept secret for 150 years by the Chamberlen family, although there is evidence for its presence as far back as 1634[citation needed].

The secret may have been sold by Hugh Chamberlen to Dutch obstetricians at the start of the 18th century in Amsterdam, but there are doubts about the authenticity of what was actually provided to buyers.

The forceps could avoid some infant deaths when previous approaches (involving hooks and other instruments) extracted them in parts.

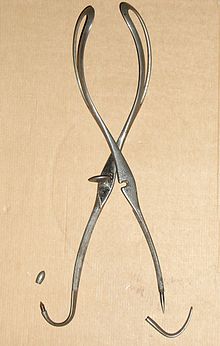

[12] In 1813, Peter Chamberlen's midwifery tools were discovered at Woodham Mortimer Hall near Maldon (UK) in the attic of the house.

[13] The tools discovered also contained a pair of forceps that were assumed to have been invented by the father of Peter Chamberlen because of the nature of the design.

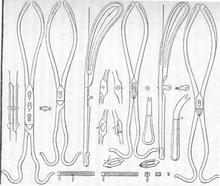

[14] The Chamberlen family's forceps were based on the idea of separating the two branches of "sugar clamp" (as those used to remove "stones" from bladder), which were put in place one after another in the birth canal.

In 1747, French obstetrician Andre Levret, published Observations sur les causes et accidents de plusieurs accouchements laborieux (Observations on the Causes and Accidents of Several difficult Deliveries), in which he described his modification of the instrument to follow the curvature of the maternal pelvis, this "pelvic curve" allowing a grip on a fetal head still high in the pelvic excavation, which could assist in more difficult cases.

Tarnier's idea was to "split" mechanically the grabbing of the fetal head (between the forceps blades) on which the operator does not intervene after their correct positioning, from a mechanical accessory set on the forceps itself, the "tractor" on which the operator exercises traction needed to pull down the fetal head in the correct axis of the pelvic excavation.

Tarnier forceps (and its multiple derivatives under other names) remained the most widely used system in the world until the development of the cesarean section.

Forceps had a profound influence on obstetrics as it allowed for the speedy delivery of the baby in cases of difficult or obstructed labour.

Over the course of the 19th century, many practitioners attempted to redesign the forceps, so much so that the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists' collection has several hundred examples.

[15] In the last decades, however, with the ability to perform a cesarean section relatively safely, and the introduction of the ventouse or vacuum extractor, the use of forceps and training in the technique of its use has sharply declined.

[18] With the introduction of obstetrical forceps, this allowed non-medical professionals, such as the aforementioned individuals, to continue to oversee childbirths.