Differential operator

This article considers mainly linear differential operators, which are the most common type.

However, non-linear differential operators also exist, such as the Schwarzian derivative.

is justified (i.e., independent of order of differentiation) because of the symmetry of second derivatives.

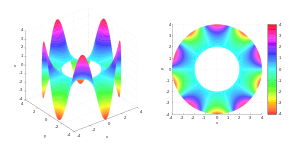

The kth order coefficients of P transform as a symmetric tensor whose domain is the tensor product of the kth symmetric power of the cotangent bundle of X with E, and whose codomain is F. This symmetric tensor is known as the principal symbol (or just the symbol) of P. The coordinate system xi permits a local trivialization of the cotangent bundle by the coordinate differentials dxi, which determine fiber coordinates ξi.

In terms of a basis of frames eμ, fν of E and F, respectively, the differential operator P decomposes into components on each section u of E. Here Pνμ is the scalar differential operator defined by With this trivialization, the principal symbol can now be written In the cotangent space over a fixed point x of X, the symbol

A differential operator P and its symbol appear naturally in connection with the Fourier transform as follows.

A more general class of functions p(x,ξ) which satisfy at most polynomial growth conditions in ξ under which this integral is well-behaved comprises the pseudo-differential operators.

The conceptual step of writing a differential operator as something free-standing is attributed to Louis François Antoine Arbogast in 1800.

[3] The most common differential operator is the action of taking the derivative.

Common notations for taking the first derivative with respect to a variable x include: When taking higher, nth order derivatives, the operator may be written: The derivative of a function f of an argument x is sometimes given as either of the following: The D notation's use and creation is credited to Oliver Heaviside, who considered differential operators of the form in his study of differential equations.

As in one variable, the eigenspaces of Θ are the spaces of homogeneous functions.

Sometimes an alternative notation is used: The result of applying the operator to the function on the left side of the operator and on the right side of the operator, and the difference obtained when applying the differential operator to the functions on both sides, are denoted by arrows as follows: Such a bidirectional-arrow notation is frequently used for describing the probability current of quantum mechanics.

This formula does not explicitly depend on the definition of the scalar product.

If Ω is a domain in Rn, and P a differential operator on Ω, then the adjoint of P is defined in L2(Ω) by duality in the analogous manner: for all smooth L2 functions f, g. Since smooth functions are dense in L2, this defines the adjoint on a dense subset of L2: P* is a densely defined operator.

This second-order linear differential operator L can be written in the form This property can be proven using the formal adjoint definition above.

We may also compose differential operators by the rule Some care is then required: firstly any function coefficients in the operator D2 must be differentiable as many times as the application of D1 requires.

To get a ring of such operators we must assume derivatives of all orders of the coefficients used.

Secondly, this ring will not be commutative: an operator gD isn't the same in general as Dg.

For example we have the relation basic in quantum mechanics: The subring of operators that are polynomials in D with constant coefficients is, by contrast, commutative.

be the non-commutative polynomial ring over R in the variables D and X, and I the two-sided ideal generated by DX − XD − 1.

Every element can be written in a unique way as a R-linear combination of monomials of the form

Every element can be written in a unique way as a R-linear combination of monomials of the form

Let E and F be two vector bundles over a differentiable manifold M. An R-linear mapping of sections P : Γ(E) → Γ(F) is said to be a kth-order linear differential operator if it factors through the jet bundle Jk(E).

In other words, there exists a linear mapping of vector bundles such that where jk: Γ(E) → Γ(Jk(E)) is the prolongation that associates to any section of E its k-jet.

This just means that for a given section s of E, the value of P(s) at a point x ∈ M is fully determined by the kth-order infinitesimal behavior of s in x.

In particular this implies that P(s)(x) is determined by the germ of s in x, which is expressed by saying that differential operators are local.

A foundational result is the Peetre theorem showing that the converse is also true: any (linear) local operator is differential.

An equivalent, but purely algebraic description of linear differential operators is as follows: an R-linear map P is a kth-order linear differential operator, if for any k + 1 smooth functions

[6] A microdifferential operator is a type of operator on an open subset of a cotangent bundle, as opposed to an open subset of a manifold.

It is obtained by extending the notion of a differential operator to the cotangent bundle.