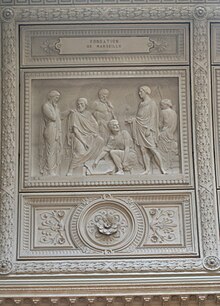

Founding myth of Marseille

Although the attested versions differ on some details, they all recount the story of the marriage of the princess Gyptis (or Petta), the daughter of Nannus, chief of the native Segobrigii, to the Phocaean sailor Protis (or Euxenus).

[2] The motif of the princess choosing her future husband in a group of suitors during her wedding is found in other Indo-European myths, notably in the ancient Indian svayamvara tales and in Chares of Mytilene's "Stories about Alexander".

The wedding was organized as follows: After the meal, the girl had to come in and offer a bowl full of wine mixed with water to whichever suitor there she wanted, and whoever she gave it to would be her bridegroom.

There is still a family in Massalia today descended from her and known as the Protiadae; because Protis was the son of Euxenus and Aristoxene.The version of Pompeius Trogus, a Gallo-Roman writer from the nearby Vocontian tribe, is now lost, but was summarized in the 3rd–4th century AD by the Roman historian Justin in his Epitoma Historiarum Philippicarum .

For the Phocaeans were forced by the meanness and poverty of their soil to pay more attention to the sea than to the land: they eked out an existence by fishing, by trading, and largely by piracy, which in those days was reckoned honourable.

It so happened that on that day the king was engaged in arranging the marriage of his daughter Gyptis: in accordance with the custom of the tribe, he was preparing to give her to be married to a son-in-law chosen at a banquet.

[2]While [the Gauls] were there fenced in as it were by the lofty mountains, and were looking about to discover where they might cross, over heights that reached the sky, into another world, superstition also held them back, because it had been reported to them that some strangers seeking lands were beset by the Salui.

The Gauls, regarding this as a good omen of their own success, lent them assistance, so that they fortified, without opposition from the Salui, the spot which they had first seized after landing....A passage from Strabo's Geographika tells part of the Phocaean journey to the foundation site and focuses on the introduction of the cult of Artemis of Ephesus to Massalia.

[8] Scholars have compared the name of the princess in Aristotle's version, Pétta (Πέττα), with the Welsh peth ('thing'), Breton pezh ('thing'), Old Irish cuit ('share, portion'), and Pictish place-names in Pet(t)-, Pit(t)-, which seem to mean 'parcel of land'.

However, Aristotle mentions that the Protiadae "descended from her" rather than from Protis, perhaps alluding to the semi-matrilineal system of the Segobrigii, where small groups were likely founded by women from the dominant tribe but ruled by local 'big men'.

[8] The Phocaean foundation myth revolves around the idea of a peaceful relationship between the natives and the settlers, which contrasted with historical situations where territories could be seized by force or trickery during the Greek colonial expansion.

[8] After the capture of Phocaea by the Persians in 545 BC, a new wave of settlers fled towards Massalia, which could explain the presence of the two chiefs (duces classis), Simos and Protis, in Trogus' version, as well as Strabo's account of the Ephesian Artemis.

In the Homeric tradition, such myths generally involve aristocratic heroes and indigenous kings who came to follow a Greek way of life via the practice of hospitality by exchanging feasts and presents, with a union eventually sealed by dowry and political alliance.

Several Indo-European myths from the Indic, Greek, and possibly the Iranian tradition, recount similar stories of princesses who choose their future husband during their own wedding or via a competition between the suitors.

[19]Athenaeus compared the Phocaean version with an Oriental tale found in Chares of Mytilene's "Stories about Alexander" (Perì Aléxandron historíai).

Odatis is supposed to look at them all, then take a golden cup, fill it and give it to the one with whom she consents to be married, but she delays once again the decision, and the frustrated Zariadre decides to kidnap the young princess.

[10] According to Aristotle, a family named Protiadae lived at his time in Massalia, and probably claimed descent from the legendary Prō̃tis (Πρῶτις), whom he portrays as the son of Euxenus and Aristoxene.